George Smith: Life & Major Discoveries of the Famed Assyriologist

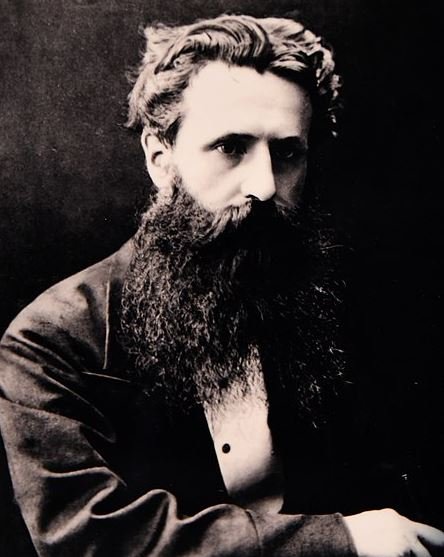

George Smith, born on March 26, 1840, in London, England, emerged as one of the most renowned figures in Assyriology.

Known for his groundbreaking discovery of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Smith’s life was marked by remarkable perseverance and self-education, as he rose from a modest background to make significant contributions to the study of ancient Mesopotamian culture.

His work not only illuminated the civilization of ancient Assyria and Babylonia but also fostered a deeper understanding of the links between ancient Mesopotamian narratives and biblical stories.

George Smith (26 March 1840 – 19 August 1876) was an influential English Assyriologist renowned for discovering and translating the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the world’s earliest known literary texts.

Early Life and Education

Smith was born into a working-class family during the Victorian era, a time when educational opportunities for lower-income families were limited. Lacking access to formal schooling, he relied heavily on his personal drive and intellectual curiosity to educate himself.

Despite the challenges of his background, Smith developed a deep interest in ancient cultures, particularly Assyrian history and Mesopotamian archaeology, from an early age. This interest would soon grow into a lifelong passion that guided him toward a career in Assyriology.

At the age of fourteen, Smith began an apprenticeship at Bradbury and Evans, a well-known publishing house in London, where he specialized in banknote engraving.

Although the work was demanding, Smith continued to pursue his interest in Mesopotamian history. His lunch breaks were often spent at the British Museum, studying newly discovered artifacts and publications related to the ancient cuneiform tablets excavated in the 1840s and 1850s by British archaeologists Austen Henry Layard, Henry Rawlinson, and Hormuzd Rassam. The cuneiform script of these tablets captured Smith’s imagination, and he dedicated himself to understanding this ancient writing system, even with limited resources.

Early Career at the British Museum

Smith’s dedication and growing knowledge of Assyriology did not go unnoticed. Samuel Birch, an Egyptologist and Director of the Department of Antiquities at the British Museum, was impressed by Smith’s enthusiasm and skill. Recognizing Smith’s potential, Birch introduced him to Sir Henry Rawlinson, a leading Assyriologist who had worked on the cuneiform inscriptions from Mesopotamia. Rawlinson quickly recognized Smith’s natural aptitude for cuneiform studies and arranged for him to work part-time at the British Museum.

Initially, Smith’s role involved sorting and cleaning countless fragile clay tablets and cylinder fragments. Despite the tediousness of this task, he was highly committed, spending hours at the museum’s storage rooms developing his skills in cuneiform reading and interpretation. This exposure to the vast collection of Mesopotamian inscriptions allowed Smith to sharpen his expertise in the ancient language and establish himself as a promising scholar.

First Major Discoveries

In 1866, Smith made his first major breakthrough: he identified the date of a tribute paid by Jehu, king of Israel, to Shalmaneser III of Assyria. This discovery solidified his reputation and demonstrated his keen ability to decode ancient inscriptions. Rawlinson, seeing Smith’s capabilities, recommended him to the trustees of the British Museum for a permanent position.

In 1870, Smith was appointed Senior Assistant in the Assyriology Department, a role that gave him more autonomy and access to resources for pursuing his research.

In 1867, Smith made two significant discoveries that further established his standing in the field. The first involved a cuneiform tablet labeled K51, which contained a record of a solar eclipse that occurred on June 15, 763 BCE. This identification became a cornerstone for ancient Near Eastern chronology, as it provided a reliable anchor date to help synchronize the timelines of Mesopotamian civilizations. Smith’s second discovery involved an inscription describing an invasion of Babylonia by the Elamites around 2280 BCE. Both findings earned him a growing reputation as a meticulous and insightful Assyriologist.

Publication and Translation Work

Smith’s reputation as an Assyriologist grew rapidly as he published his findings. In 1871, he released Annals of Assur-bani-pal, a translation and analysis of the records of Ashurbanipal, the Assyrian king known for his extensive library. That same year, he presented his research on early Babylonian history and deciphered Cypriote inscriptions at the Society of Biblical Archaeology.

However, Smith’s most significant and widely celebrated discovery occurred in 1872. While studying fragments of cuneiform tablets from Nineveh, Smith found an account that bore a striking resemblance to the biblical story of Noah’s flood. This Assyrian account described a massive flood and the survival of a chosen individual, closely paralleling the Genesis narrative. Known as the eleventh tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, this ancient story of a deluge predates the biblical account by centuries. The discovery caused a sensation, as it provided evidence of an ancient flood myth that echoed one of the most well-known stories in the Bible.

Upon realizing the significance of his discovery, Smith reacted with great excitement, famously running through the British Museum’s reading room, filled with joy. His findings garnered immediate public attention, and The Daily Telegraph offered to sponsor an expedition to Nineveh to find missing pieces of the flood story.

Expeditions to Nineveh and Further Discoveries

In early 1873, Smith embarked on his first expedition to Nineveh, funded by The Daily Telegraph. His goal was to locate additional fragments of the flood story and to learn more about Mesopotamian civilization. His expedition was successful: not only did he recover more pieces of the flood narrative, but he also uncovered records detailing the succession of Babylonian dynasties. These findings enriched the historical knowledge of Mesopotamia and provided insight into the political organization of ancient Babylonia.

Later that year, Smith returned to Nineveh, this time with financial support from the British Museum. He continued his excavations at Kouyunjik, the site of ancient Nineveh, and uncovered numerous new artifacts, including tablets that dealt with creation myths and cosmic origins. In 1875, he published Assyrian Discoveries, a comprehensive account of his fieldwork, where he described the cultural and religious context of his findings.

One of Smith’s most notable publications was The Chaldaean Account of Genesis, co-authored with Assyriologist Archibald Sayce. Published posthumously in 1880, this book provided a detailed translation and interpretation of Babylonian creation myths. The work sparked significant interest as it presented narratives from ancient Mesopotamia that paralleled stories in Judeo-Christian traditions, particularly Genesis. Smith’s translations highlighted the shared themes in these ancient cultures and underscored the interconnections between Mesopotamian and later biblical narratives.

Final Expedition and Death

In 1876, the British Museum trustees sent Smith on a final expedition to complete the excavation of the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh. This library, amassed by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, contained thousands of cuneiform texts and was one of the largest collections of ancient knowledge. However, during his travels, Smith encountered difficult conditions and ultimately fell ill with dysentery in a small village called İkizce, northeast of Aleppo. His illness worsened, and he died in Aleppo on August 19, 1876, at just 36 years old.

Smith’s early death was a significant loss to the field of Assyriology, as his work had laid a strong foundation for future scholars. Queen Victoria recognized his contributions by granting an annuity of £150 to his widow, Mary Clifton, and their six children.

Legacy and Impact on Assyriology

George Smith’s contributions to Assyriology are both profound and lasting. His discovery of the Epic of Gilgamesh brought one of the world’s oldest literary works to light, revealing the beliefs, values, and culture of ancient Mesopotamian society. The epic, which includes themes of friendship, the search for immortality, and the inevitability of death, remains one of the most influential pieces of ancient literature.

Smith’s research also had far-reaching implications for understanding Near Eastern chronology. His identification of the solar eclipse in 763 BCE provided a fixed point for aligning the timelines of various ancient civilizations, allowing future scholars to construct a more accurate historical framework. This chronology became essential for placing other Assyrian and Babylonian events within a coherent timeline.

Beyond his literary and historical contributions, Smith’s work highlighted the connections between ancient Mesopotamian and biblical narratives. His translation of the flood account not only attracted public interest but also sparked academic debates on the origins and dissemination of ancient myths. By demonstrating these links, Smith broadened the understanding of cross-cultural influences in the ancient world, showing how Mesopotamian stories and ideas could have influenced later Judeo-Christian traditions.

Conclusion

George Smith’s life exemplifies the power of dedication, intellectual curiosity, and perseverance. From a young man of humble beginnings to a pioneering Assyriologist, he made invaluable contributions to the study of ancient Mesopotamia. His translations, particularly of the Epic of Gilgamesh, opened a window into the beliefs and culture of a long-lost civilization, providing insight into the earliest human literature.

Though he faced personal and professional challenges, Smith’s passion for discovery and knowledge ultimately left a profound impact on archaeology, literature, and history. His contributions continue to inspire scholars and students of ancient history, who build upon his work to further unravel the complexities of Mesopotamian culture and its lasting legacy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was Smith’s family background, and how did it influence his education?

Coming from a working-class family, Smith had limited access to formal education. However, his passion for Assyrian history drove him to self-educate by reading extensively.

Where did Smith work at a young age, and what skills did he develop there?

At age fourteen, Smith began working as an apprentice at the publishing house Bradbury and Evans, where he learned banknote engraving.

How did Smith continue pursuing his interest in Assyriology while working?

Despite his job demands, Smith spent his lunch hours at the British Museum, studying newly unearthed cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia.

Who were some key figures who recognized Smith’s potential in Assyriology?

Samuel Birch, an Egyptologist, and Sir Henry Rawlinson, a prominent Assyriologist, both noticed Smith’s aptitude and supported his early studies.

What was Smith’s first major discovery in Assyriology?

In 1866, Smith identified the date of tribute paid by Jehu, king of Israel, to Shalmaneser III of Assyria, establishing his credibility.

What position did Smith obtain in 1870, and what did it enable him to do?

Smith became a Senior Assistant in the Assyriology Department at the British Museum, allowing him to focus on research and make further discoveries.

What were two significant inscriptions Smith found in 1867?

He discovered a record of a solar eclipse in 763 BCE on Tablet K51 and an inscription noting an invasion of Babylonia by the Elamites in 2280 BCE.

What major translation did Smith present in 1872, and why was it significant?

Smith translated an Assyrian account of a great flood, later recognized as part of the Epic of Gilgamesh. It paralleled the biblical flood story and garnered widespread attention.

How did Edwin Arnold support Smith’s research on the flood narrative?

Arnold, editor of The Daily Telegraph, funded Smith’s expedition to Nineveh to search for additional fragments of the flood story.

What additional discoveries did Smith make during his Nineveh expeditions?

Besides finding more flood story fragments, Smith uncovered records on Babylonian dynasties, shedding light on Mesopotamian rulers’ succession and reigns.

What is the significance of Smith’s work The Chaldaean Account of Genesis, published posthumously in 1880?

The book, co-written with Archibald Sayce, explored Mesopotamian creation myths, revealing ancient narratives that mirrored Judeo-Christian creation stories.

What happened to Smith during his final expedition in 1876?

Smith contracted dysentery during his journey to recover materials from Ashurbanipal’s Library in Nineveh and died on August 19, 1876, in Aleppo.

How did Queen Victoria recognize Smith’s contributions after his death?

Queen Victoria granted Smith’s family an annuity of £150 in acknowledgment of his work.

Image: Queen Victoria

What is Smith’s most notable legacy in the field of Assyriology?

Smith’s translation of the Epic of Gilgamesh brought one of the earliest literary masterpieces to global attention, enhancing our understanding of ancient Mesopotamian culture.

How did Smith’s discoveries contribute to ancient Near Eastern chronology?

His identification of historical dates, such as the 763 BCE solar eclipse, helped scholars anchor ancient Near Eastern timelines.

What impact did Smith’s work have on the study of ancient Mesopotamian and biblical narratives?

His research revealed parallels between Mesopotamian and biblical stories, broadening understanding of ancient cultural and religious connections.