The assassination of Julius Caesar on March 15, 44 BCE, known as the Ides of March, remains one of history’s most famous acts of political betrayal. This event marked a dramatic turning point in Roman history, leading to the end of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

Caesar’s assassination was orchestrated by a group of Roman senators who viewed his accumulation of power as a direct threat to Rome’s republican ideals.

These conspirators, often collectively referred to as “The Liberators,” believed they were saving the Republic from tyranny. However, their actions instead plunged Rome into chaos, sparking civil wars that ultimately cemented the power they sought to prevent.

Background: Caesar’s Rise to Power and Increasing Influence

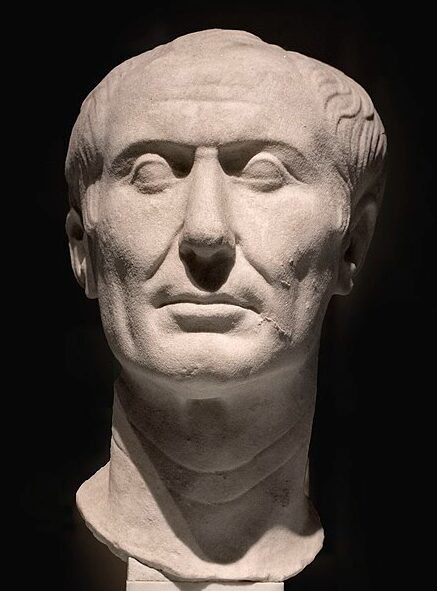

Caesar as portrayed by the Tusculum portrait

Julius Caesar was a celebrated military general and a prominent political figure in Rome who had gained extraordinary power by the mid-1st century BCE. After successful campaigns in Gaul (modern-day France and Belgium), he returned to Rome as a war hero, bringing immense wealth to the Republic.

His popularity and influence allowed him to challenge the traditional structures of Roman governance, which relied on a system of checks and balances among elected officials and institutions like the Senate.

Vercingetorix Throws Down His Arms at the Feet of Julius Caesar, 1899, by French painter Lionel Noel Royer

In 49 BCE, Caesar crossed the Rubicon River with his army, defying Roman law and initiating a civil war against the forces of the Senate, led by his former ally Pompey the Great. Caesar emerged victorious, and in 45 BCE he was appointed “dictator for life.” This title, combined with the honors and powers he accumulated, led many in the Senate to fear that Caesar intended to become a monarch—something that was anathema to the Roman Republic. Though Caesar publicly denied any ambition for kingship, he accepted honors and titles that were traditionally associated with absolute rule.

This concentration of power, alongside Caesar’s reforms that often bypassed or undermined the Senate, caused alarm among many senators. These senators saw themselves as defenders of the Republic and believed that Caesar’s death was the only way to restore traditional Roman governance.

READ MORE: The Gauls’ Long Struggle Against the Romans

Key Conspirators and Their Motivations

The plot to kill Caesar involved over 60 senators, though the primary conspirators were a smaller group led by prominent figures, each with personal and political motivations:

Marcus Junius Brutus

Brutus on Ides of March coin, minted shortly before his assassination

Brutus was perhaps the most famous conspirator, due to his close relationship with Caesar. Though Caesar had shown him favor and even treated him as a protégé, Brutus was torn between his loyalty to Caesar and his commitment to the Republic’s ideals. Brutus’ ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, had expelled Rome’s last king, establishing the Republic. Many believe that Brutus felt a personal duty to prevent any return to monarchy, and this sense of ancestral obligation may have driven him to join the conspiracy.

Gaius Cassius Longinus

The “pseudo-Corbulo” bust, likely depicting Cassius Longinus

Cassius was another leading conspirator, known for his intense opposition to Caesar’s power. Cassius was a skilled military commander but had become frustrated with Caesar’s concentration of power, which he felt undermined the traditional republican values of Rome. Unlike Brutus, Cassius harbored personal resentment toward Caesar, which may have intensified his role in the conspiracy. Cassius also played a key role in recruiting other senators to the cause, including Brutus.

Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus

Denarius of Decimus Brutus, minted in 48 BC. The obverse reads “Aulus Postumius consul,” though the specific consul is unclear (six held the title). The reverse’s wheat-ear wreath may reference a wheat supply initiated by him.

Decimus Brutus, a different Brutus than Marcus, was also a close associate of Caesar and had served under him in Gaul. Caesar trusted him, even naming him in his will as a secondary heir. However, Decimus was a staunch supporter of republican values and believed Caesar’s rule threatened the traditional governance of Rome. His involvement added credibility to the conspiracy, as he was seen as a loyalist close to Caesar.

Casca and Other Senators

Publius Servilius Casca, Tillius Cimber, and several other senators also joined the plot, each driven by a mixture of fear for the Republic and personal grievances. Casca was the first to strike Caesar during the assassination, a symbol of the urgency and desperation among the conspirators. Many of the lesser-known senators were motivated by a shared belief in protecting the Republic, but others likely joined out of a desire for personal advancement or from resentment toward Caesar’s perceived favoritism and disregard for Senate authority.

The Assassination Plot

The conspirators carefully planned Caesar’s assassination, choosing to strike on the Ides of March, when Caesar was scheduled to attend a Senate meeting at the Theatre of Pompey.

The venue itself was symbolic; Pompey the Great had been Caesar’s rival, and the Senate meetings there were a reminder of the Republic’s earlier power structure.

The conspirators expected Caesar to arrive without his bodyguard, as he often did when among senators, whom he viewed as his peers and trusted colleagues.

Julius Caesar

Reports suggest that Caesar was warned of the plot by various omens and individuals, including a soothsayer famously telling him to “beware the Ides of March.” His wife, Calpurnia, also had troubling dreams and urged him to stay home. However, Caesar ultimately dismissed these warnings, either out of confidence or a sense of fatalism, and attended the Senate meeting as planned.

The Ides of March: Assassination in the Senate

On 15 March 44 BC, Octavius’s adoptive father Julius Caesar was assassinated by a conspiracy led by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome. Image: The Death of Caesar by Italian painter Vincenzo Camuccini (1771-1844).

On March 15, 44 BCE, Caesar entered the Theatre of Pompey, where the Senate had convened. As he took his seat, he was surrounded by the conspirators. Tillius Cimber approached Caesar, ostensibly to present a petition. As Caesar refused the request, Cimber grabbed his toga, signaling the other assassins to strike. Casca was the first to attack, stabbing Caesar in the shoulder.

The first wound Caesar sustained was to the neck. It was delivered by Servilius Casca, and soon, Caesar found himself under attack by a mob of mutinous senators.

Chaos erupted as the other conspirators joined in, stabbing Caesar a total of 23 times. According to historical accounts, Caesar initially attempted to fight off his attackers but stopped resisting when he saw Brutus among them.

Caesar was stabbed across his entire body, from his face, back, and thighs. He was stabbed a total of 23 times.

Caesar’s famous last words, “Et tu, Brute?” (And you, Brutus?), though likely apocryphal, have become legendary as a symbol of ultimate betrayal. In reality, some historians believe Caesar may have said nothing, or merely uttered a resigned exclamation upon realizing Brutus was involved.

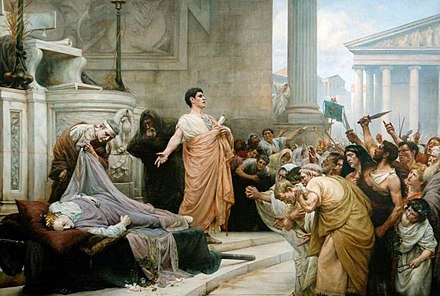

Following the assassination of Julius Caesar, Rome descended into chaos as supporters of the slain dictator fought against the senate. Image: La Mort de César by French painter Jean-Léon Gérôme

Immediate Aftermath and Public Reaction

The conspirators expected to be hailed as heroes who had saved the Republic. However, their actions had unintended consequences. Caesar’s death shocked the Roman populace, many of whom admired him for his military successes and reforms. Instead of viewing the assassination as an act of liberation, the public reacted with confusion, fear, and, in some cases, anger.

Mark Antony, Caesar’s loyal ally, skillfully managed public sentiment in the days following the assassination. During Caesar’s funeral, Antony delivered a powerful oration that emphasized Caesar’s achievements and subtly condemned the assassins. By displaying Caesar’s bloodstained toga and reading his will—which generously left money to Roman citizens—Antony stirred the people’s emotions, turning the public against the conspirators.

Riots broke out in Rome, and the conspirators were forced to flee. Their vision of restoring the Republic quickly disintegrated, as civil unrest led to further power struggles.

Marc Antony’s Oration at Julius Caesar’s Funeral as depicted by George Edward Robertson

The Civil War and the End of the Republic

Following Caesar’s death, Rome descended into chaos. Mark Antony, Octavian (Caesar’s adopted heir), and Marcus Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate, a political alliance aimed at avenging Caesar and restoring order. The Triumvirate waged a brutal campaign against Caesar’s assassins and their supporters. Cassius and Brutus, who had fled to the eastern provinces to raise armies, were defeated in the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE, where both committed suicide rather than face capture.

The civil war following Caesar’s assassination devastated Rome and ultimately led to the collapse of the Republic. Octavian eventually emerged as the victor, consolidating power under the title Augustus and becoming Rome’s first emperor. Ironically, the assassins’ attempt to preserve the Republic instead ushered in a new era of imperial rule, marking the beginning of the Roman Empire.

Legacy of Caesar’s Assassination

Possible posthumous bust of Julius Caesar, marble portrait, dated 44–30 BCE, Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums.

The assassination of Julius Caesar is remembered as a profound act of political violence, motivated by a complex mix of ideals, personal grievances, and political calculations. The conspirators viewed themselves as liberators defending republican values, yet their actions led to the very outcome they had sought to prevent. Caesar’s death did not restore the Republic; rather, it exposed the deep divisions within Roman society and accelerated the transition from republic to empire.

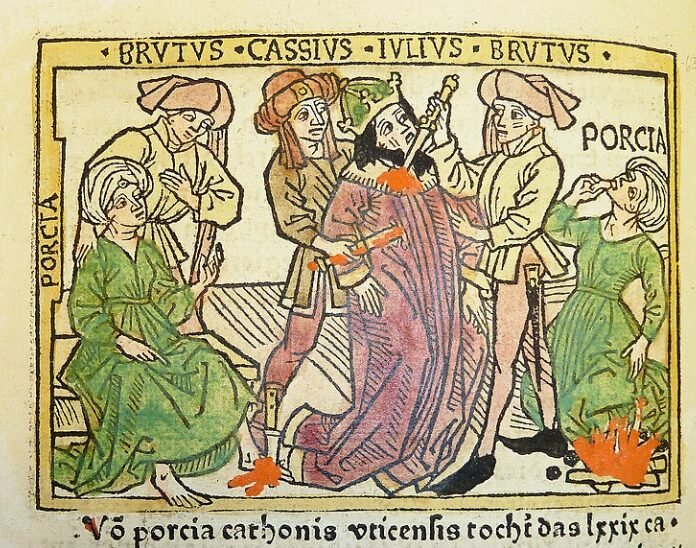

A woodcut manuscript illustration by Johannes Zainer, anachronistic, circa 1474.

Caesar’s assassination has resonated through history as a symbol of betrayal and the dangers of unchecked ambition. The event has inspired countless works of literature, most famously William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, which explores themes of loyalty, power, and the consequences of political assassination. The Ides of March, once a simple date on the Roman calendar, is now remembered worldwide as a warning against betrayal and the potential consequences of political violence.

In modern times, Caesar’s assassination continues to be studied as a pivotal moment that exemplifies the complexity of political power, loyalty, and the unpredictable consequences of radical actions. The assassins believed they were rescuing Rome from tyranny, but instead, they set in motion a chain of events that would forever alter the course of Roman—and world—history.

Tillius Cimber (center) presents the petition, pulling Caesar’s tunic, as Casca behind readies to strike; painting by German painter Karl von Piloty.