History of Tenochtitlan: When and how was it destroyed by the Spanish?

Tenochtitlán was an Aztec city built on an island in Lake Texcoco (modern-day Mexico City) between 1325 and 1521, featuring a system of canals and causeways for transportation and supply.

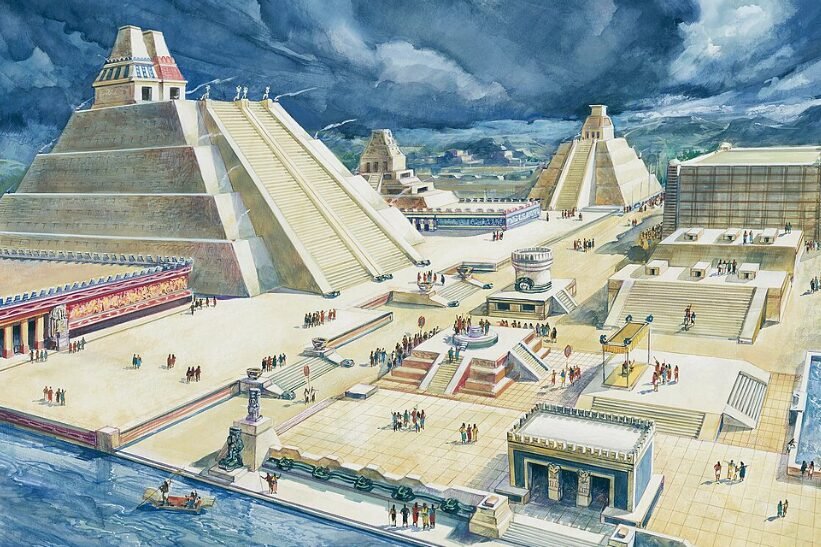

Tenochtitlán was the ancient capital of the Aztec empire, situated in the marshes of Lake Texcoco on the site of modern Mexico City. Image: The Templo Mayor in Mexico-Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital.

What was Tenochtitlán and where was it located?

Tenochtitlan was a remarkable urban center established by the Mexica people on an island in Lake Texcoco, in what is now the heart of Mexico City.

Though historians are not entirely certain of the exact date of its founding, tradition situates it in the early fourteenth century. Over the centuries, it grew into the beating heart of the Mexica Empire, reaching its apex in the fifteenth century as the largest city in the pre-Columbian Americas. This achievement owed much to the civilization’s sophisticated engineering, trade networks, and religious life.

Yet, in 1521, the city fell to Spanish conquistadors and their Indigenous allies, who dismantled much of its ceremonial core.

Despite extensive destruction, remnants of Tenochtitlan lie beneath the historic center of Mexico’s bustling capital, acting as a silent witness to the grandeur of a city once unmatched in Mesoamerica.

“Prickly Pear”

The name “Tenochtitlan” has traditionally been connected to Nahuatl words for “rock” (tetl) and “prickly pear” (nōchtli), which some interpret as “Among the prickly pears growing among rocks.”

However, ambiguity persists in linguists’ analyses of the term, partly because a sixteenth-century manuscript suggests that the second vowel in the word may have been short.

Others believe the name could also be traced back to Tenoch, a key leader whose importance was immortalized in various oral traditions. In any case, the city’s name is deeply woven into Mexica identity.

Geographic Setting

Location of Tenochtitlan

Lake Texcoco, situated in the Valley of Mexico, once supported five interconnected lakes. Tenochtitlan and its sister settlement Tlatelolco lay on a western island in these shallow waters. The lake, created by an endorheic basin, contained brackish water.

Through strategic construction—most famously, the levee of Nezahualcoyotl in the mid-fifteenth century—the Mexica were able to keep fresh water near their island, while limiting the encroachment of brackish water on the eastern side of Lake Texcoco.

In addition, Tenochtitlan was connected to the mainland by causeways and bridges, enabling foot traffic, canoe passage, and the possibility of defense against outside threats.

Urban Infrastructure

At its peak, Tenochtitlan covered an area ranging between 8 and 13.5 square kilometers. The central district was organized around a ceremonial core, while neighborhoods (calpullis) stretched outward in a grid-like layout defined by canals. These canals and causeways allowed residents to traverse the city on foot or by canoe. Freshwater aqueducts, several kilometers long, channeled pure water from springs at Chapultepec.

Tenochtitlán featured several causeways linking it to the mainland, the palace of Montezuma II with hundreds of rooms, and numerous temples.

Although the inhabitants often used this water for washing, wealthier families preferred mountain spring water for drinking. Bathing was culturally significant; many residents bathed daily, and noble families also enjoyed temāzcalli (sweat baths) for ritual purification and relaxation.

Public structures anchored the city’s ceremonial life. Inside a walled square at the heart of Tenochtitlan stood key temples and administrative buildings. The most important was the Templo Mayor, dedicated jointly to Huitzilopochtli (the Mexica patron deity of warfare and the sun) and Tlaloc (the god of rain and fertility). Surrounding it were additional temples, ball courts, and a rack of skulls known as the tzompantli, all of which underscored the city’s religious significance and the prominent role of ritual in Mexica society.

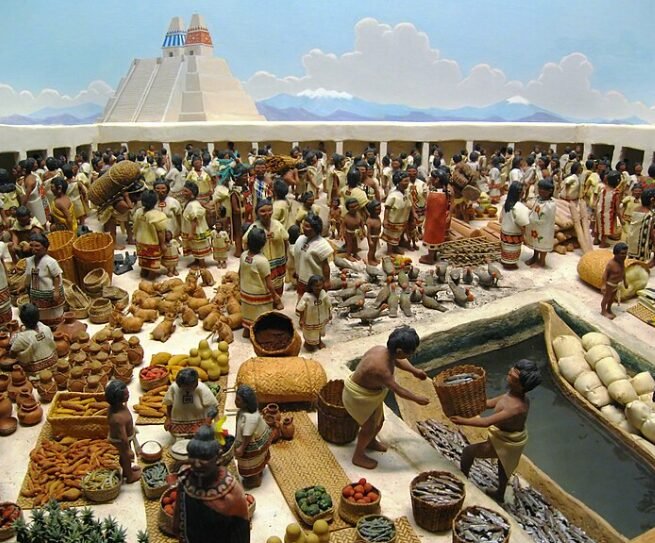

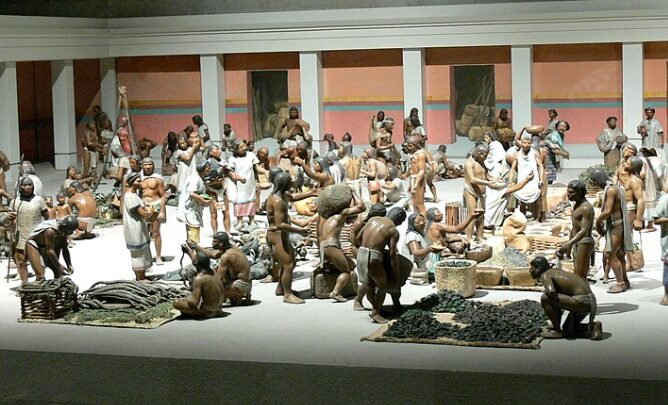

Extensive engineering achievements, from levees to aqueducts, allowed for the maintenance of fresh water and facilitated travel by boat or on foot. Elaborate architectural projects, including temples and palaces, showcased the city’s wealth and imperial reach. Image: The Tlatelolco Marketplace as depicted at The Field Museum in Chicago.

Political Structure and Social Classes

Tenochtitlan was divided into four principal zones, each containing a number of calpullis. A calpulli functioned as a district or clan-based organization, sometimes reflecting kinship ties or a combination of geographic proximity and political alliances.

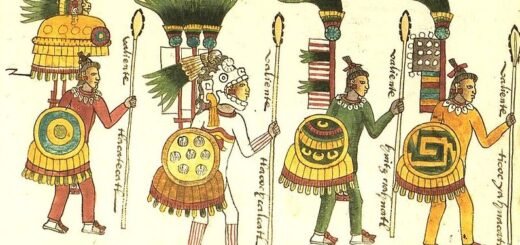

Nobles (pipiltin) managed administrative and ritual duties, whereas commoners (macehualtin) tended crops and performed various trades. Social mobility, while limited, was possible: individuals with exceptional martial prowess might become “eagle nobles,” earning privileges typically reserved for the elite.

Meanwhile, merchants (pochteca) established far-ranging trade networks across Mesoamerica, returning with goods that fueled Tenochtitlan’s economic might. Their wealth, however, came with the expectation of sponsoring important religious ceremonies.

A sophisticated social hierarchy governed everyday life, with calpullis anchoring communities, and distinct classes shaping political power and cultural expression. Image: Reconstruction of an Aztec market in Tenochtitlan in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

Housing also illustrated social boundaries. Commoners inhabited structures of reeds and mud, often with thatched roofs, whereas nobility dwelt in larger masonry compounds. The calpulli’s organization allowed communities to remain relatively cohesive, balancing the obligations of labor, tribute, and cultural customs within a society that, by some estimates, encompassed hundreds of thousands of people in Tenochtitlan alone.

Historical Development and Growth

The Mexica viewed Tenochtitlan’s founding as the culmination of a prophecy: an eagle perched on a cactus, holding a serpent, would signal the place where they were destined to settle. They discovered this sign on a small, marshy island in Lake Texcoco and, despite challenging conditions, gradually transformed that island into a thriving metropolis.

With strategic alliances and military campaigns, the Mexica consolidated power throughout the Valley of Mexico. Their empire expanded beyond neighboring polities to extend its reach across vast swaths of central and southern Mexico.

By the late fifteenth century, Tenochtitlan’s architecture and infrastructure reflected the city’s prosperity. Magnificent temples and palaces, intricate chinampas (raised agricultural beds), and regular marketplaces underscored its role as an economic and cultural powerhouse.

Valuable goods and tribute flowed into Tenochtitlan, fueling a population that some historians estimate to have been between 200,000 and 400,000 inhabitants at its zenith. Tlatelolco’s vast marketplace, reputedly accommodating tens of thousands of traders daily, further enhanced Tenochtitlan’s economic significance.

Conquest and Aftermath

In 1519, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés arrived in the region. Initially, he established alliances with Indigenous groups resentful of Mexica rule. As he advanced toward Tenochtitlan, the city’s ruler, Moctezuma II, chose to greet him diplomatically rather than provoke an immediate military conflict. The Spaniards marveled at Tenochtitlan’s scale and complexity—chroniclers likened its towers and buildings rising from the water to something out of a dream.

Spanish conquistadores, led by Hernán Cortés, besieged and destroyed Tenochtitlán in 1521.

However, diplomacy quickly gave way to tension. Spanish forces committed acts of violence, especially during religious festivals they interpreted as potential traps. Hostilities mounted, and Cortés eventually seized Moctezuma II. A brief respite followed when the Spaniards left the city, but in 1521, Cortés returned with an allied force that included tens of thousands of Indigenous warriors.

The ensuing siege of Tenochtitlan lasted over 90 days. Famine, disease—particularly smallpox—and the superior weaponry of the conquistadors led to the Mexica’s defeat in August 1521. With that collapse, the once-mighty city fell under Spanish control.

Colonial Transition

Following the destruction wrought by the conquistadors, Cortés ordered that Tenochtitlan be rebuilt in a manner reflecting Spanish urban sensibilities. The city’s ceremonial heart—most notably the Templo Mayor—was methodically demolished, and a cathedral rose in its place.

As Mexico City (which absorbed Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco) emerged as a colonial center, Spanish authorities established a jurisdiction known as the traza for Europeans, surrounded by Indigenous districts.

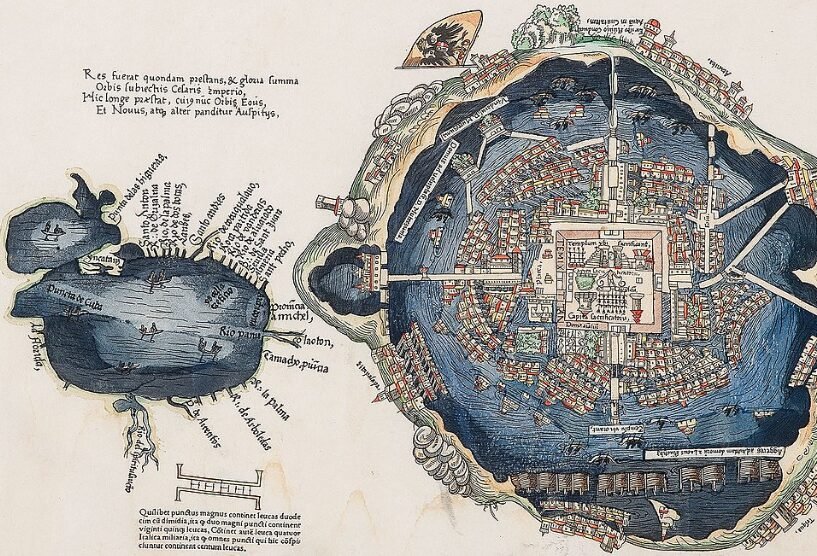

First European map of Tenochtitlan, 1524

Although many Mexica had perished or fled during the siege, Indigenous communities continued to inhabit portions of the city. Over time, Spanish governance introduced new social and economic structures, yet the local population resisted complete assimilation, retaining many linguistic and cultural traditions.

Documentation from the colonial era, including legal disputes over property and tribute obligations, reveals the resilience of Indigenous social frameworks. Even under foreign rule, many Mexica leaders maintained a degree of autonomy in their neighborhoods, though subject to Spanish crown authorities. This dual arrangement shaped Mexico City’s early colonial identity, blending Spanish-imposed institutions with remnants of Mexica communal organization.

Contemporary Remnants

Today, much of Tenochtitlan lies buried beneath the streets of modern Mexico City’s historic center. Nonetheless, archaeologists continue to uncover vestiges of its glorious past. In the late 1970s, workers stumbled upon a massive stone disc depicting the dismembered moon goddess Coyolxauhqui. This find led to significant excavations around the Templo Mayor, where layers of construction reveal successive eras of temple expansion and remodeling.

Modern-day Mexico City overlays Tenochtitlán’s ruins, and archaeological discoveries like the Templo Mayor, ball courts, and ceremonial artifacts reveal its historical and cultural significance. Image: Templo Mayor of Mexico-Tenochtitlan ruins.

Other evidence of Tenochtitlan’s infrastructure appears in the city’s layout. Several major avenues trace the paths of ancient causeways once used for trade and defense. Visitors to the capital can explore museums and exhibits containing artifacts, from ritual sculptures to everyday household items.

Timeline

1521 marks the fall of Tenochtitlán and the Aztec Empire to Hernán Cortés and his conquistadors, a foundational moment often viewed through a European perspective that has dominated the narrative for centuries. Image: A Mexico City monument commemorating the founding of Tenochtitlan

- 1325: The Mexica found Tenochtitlán on an island in Lake Texcoco, guided by an omen of an eagle perched on a cactus. They construct the earliest dwellings amid terrain.

- 1428: The city breaks free from powerful Azcapotzalco. Forming strategic alliances, Tenochtitlán quickly becomes a dominant force in the region.

- Mid-15th century: Monumental architecture flourishes, including the Templo Mayor. The Mexica refine causeways, canals, and aqueducts, enhancing the city’s water supply.

- 1486–1502: Ruler Ahuitzotl oversees reconstruction after flooding, expanding Tenochtitlán’s influence through trade and conquest.

- 1519: Hernán Cortés arrives. Emperor Moctezuma II welcomes him, hoping diplomacy will avert hostilities.

- 1520: During the Toxcatl festival, Spanish forces led by Pedro de Alvarado attack, igniting unrest.

- 1521: After a protracted siege and the spread of smallpox, Tenochtitlán falls. Cortés establishes a new colonial center, reshaping the city’s layout.

- 1522: European prints depicting the city emerge, showing its grandeur and the complexity of its urban planning.

- 1925: Authorities choose 13 March 1325 as the official date to honor the city’s six-century legacy.

- 1978: Workers discover the Coyolxauhqui Stone, prompting excavations of the Templo Mayor.

- 1987: Archaeologists unearth a mass of human bones near Templo Mayor, offering insights into Mexica rituals.

Frequently Asked Questions

A photo of Tenochtitlan and Templo Mayor model at Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology.

Who were the Mexica, and how does this term differ from Aztecs?

The Mexica were the people of Tenochtitlán, while “Aztec” broadly refers to various groups within the broader Aztec civilization of Central Mexico. Not all Aztecs were Mexica, though the terms are often used interchangeably.

The distinction between Mexica and Aztecs important because it reflects a deeper understanding of the cultural and linguistic diversity of the region and highlights the complexities of identity within the Aztec civilization.

When and where was Tenochtitlan founded?

It was established around 1325 on two small islands in Lake Texcoco and later expanded by building artificial islands.

How large and populous was it by 1519?

By 1519, Tenochtitlán covered about five square miles (13 square km) and had a population of about 400,000 people, making it the largest concentration in Mesoamerica.

Tenochtitlán joined with Texcoco and Tlacopán, becoming the Aztec capital by the late 15th century. Image: Panoramic view of Templo Mayor showcasing archaeological remains in Mexico City’s Historic Center.

What was the significance of the Templo Mayor?

The Templo Mayor was a sacred pyramid dedicated to Huitzilopochtli (god of war) and Tlaloc (god of rain). It was a site for rituals, including human sacrifices, central to Aztec religion.

How was Tenochtitlán socially and politically organized?

The city was divided into clan groups (calpulli) led by nobles (pipiltin), with a strict class hierarchy dictating social roles, attire, and property. Education emphasized morality, religion, and physical discipline.

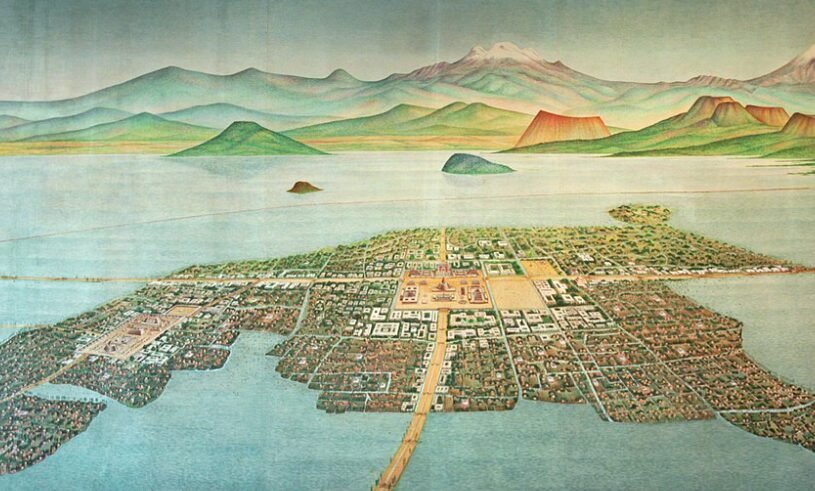

The city became an economic hub after conquering Tlatelolco in 1474, using bartering systems with cacao beans, cotton blankets, and gold dust. Metallurgy also played a significant role. Image: Tenochtitlan and Lake Texcoco in 1519

What writing system did the Aztecs use?

The Aztecs used a pictorial writing system, blending images and symbols. Codices made from fig tree bark documented their history but were mostly destroyed by Spanish priests.

What led to the destruction of Tenochtitlán?

Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés besieged and largely destroyed Tenochtitlán in 1521, aided by a smallpox epidemic and alliances with local enemies of the Aztecs.

Initially welcomed with gifts, Cortés imprisoned Motecuhzoma II, leading to political turmoil. After a brief retreat, he returned with an army of Spaniards and native allies to conquer the city.

What were the key factors in the fall of Tenochtitlán?

The siege combined military strategies, destruction of the aqueduct, food shortages, and a devastating smallpox epidemic, culminating in the city’s collapse in August 1521.