Clotho: Spinner of the Thread of Human Life

Clotho (Roman equivalent Nona) spun the thread of life from her distaff onto her spindle. Image: Bas relief of Clotho, lampstand at the U.S. Supreme Court

Clotho, one of the Three Fates (Moirai) in Greek mythology, is a powerful figure who holds significant influence over the course of human life.

As the spinner of the thread of life, Clotho is responsible for initiating the journey of every being, mortal and divine, by determining the moment of their birth.

Her role is essential in Greek mythological narratives, symbolizing the beginning of life and the inevitable progression toward its end.

Alongside her sisters, Lachesis and Atropos, Clotho weaves a narrative of destiny that is inescapable for all, including the gods themselves.

The Role of Clotho in the Moirai

In Greek mythology, the Moirai—Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos—were the personifications of fate. Together, they controlled the destiny of every individual. Clotho, the youngest, was responsible for spinning the thread of life, thus beginning each person’s existence.

Clotho’s sister Lachesis measured the length of the thread, determining how long a life would last, while Atropos, the eldest, cut the thread, signifying death.

Clotho was seen as having immense power over the very fabric of human and divine existence.

The Moirai were feared and respected for their control over life and death, a power that even the gods could not alter.

Clotho’s role as the spinner of life underscores the ancient Greek belief in the fragility and preordained nature of existence. The thread she spun represented not only the physical lifespan of an individual but also the events, choices, and experiences that would shape their life. By controlling the beginning of life, Clotho was seen as having immense power over the very fabric of human and divine existence.

Origins and Lineage of Clotho

Clotho, like her sisters, has varying origin stories in Greek mythology. One of the earliest accounts of the Moirai comes from Hesiod’s Theogony, where they are described as the daughters of Nyx, the primordial goddess of Night. This origin emphasizes their connection to the darker, more mysterious aspects of existence, such as death and fate.

However, later in Theogony, the Moirai are also described as the daughters of Zeus, the king of the gods, and Themis, the goddess of divine law and order. This version aligns the Fates with the moral order of the cosmos, indicating that their control over life and death is part of the universe’s lawful structure.

In Plato’s Republic, Clotho is further depicted as the daughter of Ananke, or Necessity. Ananke was a figure representing the inevitable and unalterable nature of fate, thus reinforcing Clotho’s role in ensuring that life unfolds according to a predetermined plan. This philosophical interpretation suggests that Clotho’s actions, though impactful, are not random or arbitrary, but rather part of a larger cosmic order.

In Roman mythology, Clotho’s equivalent is known as Nona, named after the ninth month of pregnancy, a symbol of her association with birth and the beginning of life. In this way, the Romans adapted Clotho’s role to their own cultural context, linking her with the crucial moments of human existence.

READ MORE: The Birth of the Gods, according to ancient Greek poet Hesiod

Clotho’s Powers and Influence

Clotho’s influence extended beyond merely spinning the thread of life. In many myths, she had the power to make significant decisions about who would live or die, and even the ability to restore life.

One of the most famous examples of her life-giving powers is found in the myth of Tantalus, a man who killed and served his son Pelops to the gods. When the gods realized what Tantalus had done, they restored Pelops to life, with Clotho playing a central role in this resurrection. This story highlights her ability to manipulate life and death in ways that even other gods could not.

Clotho was also involved in other major mythological events. For example, she is said to have weakened the monstrous Typhon by feeding him poisoned fruit, helping the gods defeat this powerful enemy.

Together with her sisters and Hermes, Clotho was credited with inventing the alphabet.

In another myth, Clotho helped persuade Zeus to kill Asclepius, the god of medicine, when his abilities to heal and even resurrect the dead were seen as a threat to the natural order of life and death. These stories underscore Clotho’s role in maintaining balance in the universe, ensuring that no one, not even a god, could overturn the fate she and her sisters had woven.

Furthermore, Clotho’s influence extended to the realm of human civilization. Along with her sisters and the god Hermes, Clotho was credited with the invention of the alphabet, a symbol of the importance of communication, knowledge, and the recording of human events. This further cements her role as a figure who not only controls life’s beginning but also plays a part in shaping human culture and history.

Myths Involving Clotho

Clotho appears in various myths, often playing a pivotal yet understated role in the unfolding of events.

One of the more intriguing myths involving her is that of Alcestis and Admetus. Admetus, a mortal king, was granted the favor of living beyond his destined time if he could find someone to die in his place. His wife, Alcestis, offered herself, and as she was being taken to the underworld, Heracles (Hercules in Roman Mythology) intervened. In some versions of the myth, it is Clotho who facilitates the agreement that allows Admetus to live longer, showcasing her ability to alter fate under certain conditions.

Another myth that highlights the Fates’ power over life and death is the story of Meleager. When Meleager was born, the Moirai prophesied that he would die when a particular log in the hearth was consumed by fire. His mother, Althaia, saved the log to protect her son. However, in a fit of rage after Meleager killed her brothers, she threw the log into the fire, thus sealing his fate. This tale illustrates how Clotho, by spinning the thread of life, sets in motion a series of events that even familial love or anger cannot prevent.

READ MORE: The Moirai and Meleager in Greek Mythology

Worship of Clotho and the Moirai

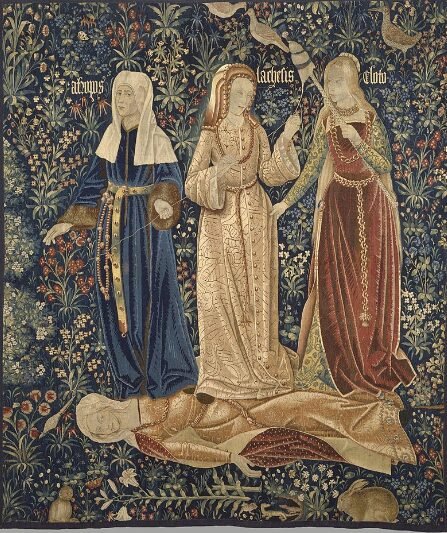

Image: The three Moirai, or the Triumph of death, Flemish tapestry, c. 1520 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

In ancient Greece, Clotho and her sisters were worshipped as goddesses of fate. They were revered in many cities, with temples and altars dedicated to them. The Moirai were often invoked during important life events, such as births, marriages, and funerals, as these were the moments where fate was most apparent. People believed that the Moirai could be placated or appeased through offerings and prayers, in the hope of securing a favorable destiny.

Clotho’s presence in religious practices often overlapped with other deities associated with life and death, such as the Keres (spirits of violent death) and the Erinyes (Furies), goddesses of vengeance. These connections reinforce the idea that Clotho was not only a bringer of life but also a guardian of the natural balance, ensuring that those who defied fate or the moral order were punished.

Brides in ancient Greece sometimes offered locks of their hair to Clotho and her sisters, symbolizing their submission to fate as they entered a new chapter of life. Similarly, women would swear oaths by the Moirai, indicating the deep respect and reverence the ancient Greeks had for these goddesses. The Moirai were also frequently invoked during childbirth, as Clotho was believed to be responsible for the fate of the newborn.

Symbolism of Clotho

The symbolism of Clotho is deeply tied to the fragility of life and the inescapability of fate. Her spinning of the thread represents the beginning of life, but it also underscores how life is interconnected with time, chance, and the decisions made by higher powers. The thread itself is a powerful metaphor for the human lifespan, suggesting that life is both delicate and subject to forces beyond individual control.

Clotho’s spindle, the tool with which she spins the thread of life, is a key symbol in Greek mythology. The spindle represents creation and the continuity of life, but it also highlights the mechanical, almost impersonal nature of fate. While individuals may make choices throughout their lives, their ultimate fate is determined by the thread that Clotho spins, emphasizing the tension between free will and destiny.

Though worshiped as goddesses, Clotho’s role focused on representing the inevitability of fate in human existence.

Moreover, the imagery of Clotho spinning life’s thread has influenced later representations of fate in art, literature, and philosophy. In many cultures, the act of spinning is associated with creativity, continuity, and the unfolding of time. Clotho’s role as the spinner of life taps into these universal themes, making her a figure whose influence extends far beyond ancient Greece.

Parallels in Other Cultures

The concept of fate and the personification of its control by supernatural figures is not unique to Greek mythology. Many cultures have similar deities or entities that oversee destiny.

In Norse mythology, the Norns—Urðr (fate), Verðandi (becoming), and Skuld (debt)—are three female figures who, like the Moirai, control the destiny of gods and men. They are often depicted as weaving the threads of life at the base of Yggdrasil, the world tree, mirroring the Moirai’s role in Greek mythology.

The norns Urðr, Verðandi, and Skuld beneath the world tree Yggdrasil (1882) by German painter Ludwig Burger.

In Roman mythology, Clotho is equivalent to Nona, who, along with her sisters Decima (Lachesis) and Morta (Atropos), governs the fate of all beings. These Roman Fates, or Parcae, had a similar function to the Greek Moirai but were often associated with more Roman-specific cultural ideas about birth and life.

In Baltic mythology, the goddess Laima, along with her sisters Kārta and Dēkla, performed roles similar to the Moirai, determining the fate of individuals, particularly newborns. Like Clotho, Laima was associated with the beginnings of life, further demonstrating the widespread cultural belief in the inevitability of fate.

In Roman mythology, her equivalent was Nona. Image: The Triumph of Truth (The Three Parcae Spinning the Fate of Marie de Medici) (1622–1625), by Flemish artist Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Did you know…?

There isn’t a singular epic tale where the Fates are the main focus, but they play crucial roles in many stories involving gods and mortals.

Inescapable nature of fate

Clotho’s legacy in Greek mythology extends far beyond her role as one of the Three Fates. As the spinner of life, she is a symbol of creation and destiny, embodying the ancient Greek understanding of life’s transience and the inescapable nature of fate. Her role in myths and religious practices highlights the importance of recognizing the limits of human control over life’s events and outcomes.

In literature and philosophy, Clotho has continued to inspire reflections on fate, free will, and the meaning of life. The image of the spinning thread has become a powerful metaphor for the human condition, representing both the beauty and fragility of existence. Image: Clotho, 1893 by French sculptor Camille Claudel.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who are the Three Fates in Greek mythology, and what are their roles?

The Three Fates are Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos. Clotho spins the thread of life, Lachesis measures it, and Atropos cuts it, determining the moment of death.

What are the different origin stories of the Moirai in Greek mythology?

In Hesiod’s Theogony, the Moirai are either daughters of Nyx (Night) or daughters of Zeus and Themis. Plato’s Republic describes Clotho as the daughter of Necessity, a representation of fate’s inevitability.

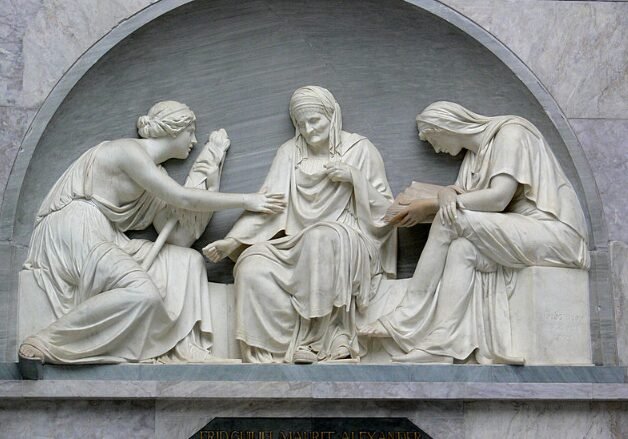

Clotho’s sisters, Lachesis and Atropos, respectively measured and cut the thread, determining a person’s lifespan and death. Image: The three Moirai, relief, grave of Alexander von der Mark [de] by Johann Gottfried Schadow (Old National Gallery, Berlin)

In Roman mythology, Clotho is considered the daughter of Uranus and Gaia, reinforcing the Fates’ connection to primordial forces.

What significant events does Clotho influence in Greek mythology?

Clotho helps create the alphabet with Hermes, weakens the monster Typhon with poisoned fruit, and persuades Zeus to kill Asclepius to maintain the natural order of life and death.

In ancient Greek religion, the Moirai were female deities who controlled human and divine destinies, determining birth, death, and suffering. They are the Roman equivalent of the Parcae. Image: Les Parques (“The Parcæ”), French painter Alfred Agache, c 1885

How does Clotho demonstrate her power in the myth of Tantalus and Pelops?

After Tantalus kills his son Pelops, Clotho uses her life-giving powers to resurrect Pelops, except for a shoulder, which is replaced with ivory.

Beyond spinning life’s thread, Clotho had the power to save or end lives, such as when she resurrected Pelops. Image: Pelops and Hippodamia racing in a bas-relief (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

What is Clotho’s role in the myth of Alcestis and Admetus?

Alcestis tricks Clotho and the Fates into revealing that Admetus could escape death if someone replaced him. Alcestis offers herself, but Heracles later intervenes and saves her, allowing her to reunite with Admetus.

How do the Fates play a role in the story of Meleager?

The Fates prophesy that Meleager’s life will end when a burning log is consumed. His mother, Althaia, eventually ignites the log in a fit of rage, leading to Meleager’s death.

What do the Moirai symbolize in Greek mythology?

The Moirai symbolize the inescapable nature of fate and destiny, governing life and death for both mortals and gods.

How were the Fates, including Clotho, worshipped in ancient Greece?

The Fates were honored throughout Greece, often associated with deities like the Keres and Erinyes, reflecting their roles in both life, death, and the moral order.