How was the Iran-Contra Affair Exposed?

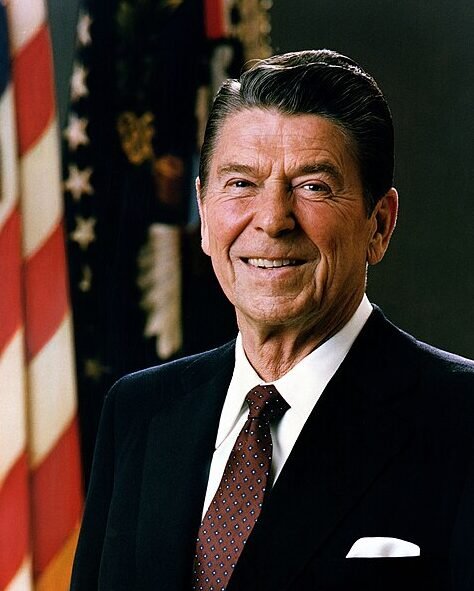

The Iran-Contra Affair was a complex political scandal that unraveled during Ronald Reagan’s second term as president in the 1980s. The affair involved secret arms sales to Iran, a country under an arms embargo, and the illegal diversion of the proceeds to fund the Contras, an anti-communist rebel group in Nicaragua. This circumvented U.S. law, specifically the Boland Amendment, which prohibited further U.S. aid to the Contras.

The affair was marked by clandestine operations, internal disputes within the Reagan administration, and a subsequent cover-up attempt.

However, through a combination of investigative journalism, leaks, and government inquiries, the Iran-Contra Affair came to light, exposing the intricate web of illegal activities and political maneuvering at its core.

Early Clues and Leaks

The early stages of the Iran-Contra Affair began with the Reagan administration’s efforts to secure the release of American hostages held by Hezbollah, a Lebanese militant group with ties to Iran. The administration sought to use arms sales to Iran, despite an arms embargo on the country, as a bargaining chip to influence Hezbollah. The idea was that Iran, a Shiite power with influence over Hezbollah, could pressure the group into releasing the hostages.

The arms sales began in secret, with Israel acting as an intermediary in the initial exchanges. Israel sold U.S. arms to Iran, and the United States replenished Israel’s supplies. The proceeds from these sales were then diverted to fund the Contras, despite Congress explicitly forbidding this through the Boland Amendment.

Although these operations were covert, some in the media, Congress, and the intelligence community began to notice irregularities. For instance, by the mid-1980s, U.S. government officials and journalists had started to raise questions about the administration’s involvement with the Contras, as well as the nature of U.S.-Iran relations, which were meant to be hostile.

Israel-United States Relation and its impact on the Middle East Peace Process

Public Exposure Begins: The Lebanese Press

The first major breakthrough came not from American media, but from the Middle East. On November 3, 1986, the Lebanese newspaper Al-Shiraa published an explosive report, revealing that the United States had secretly sold arms to Iran in exchange for the release of American hostages. The article disclosed details about U.S. officials negotiating with Iranian intermediaries, which sent shockwaves through the political world, both in the U.S. and abroad.

Al-Shiraa’s report caught the attention of global media outlets, and it wasn’t long before American news organizations began investigating the story. While Al-Shiraa focused on the hostages-for-arms aspect of the scandal, subsequent investigations began to uncover more disturbing facts about the diversion of funds to the Nicaraguan Contras. This was the first major step in exposing the scandal and set in motion a chain of events that would eventually lead to broader government investigations.

The Iran-Contra Affair revealed a covert network of operations within the Reagan administration, involving the illegal sale of arms to Iran and the funding of Nicaraguan rebels in defiance of congressional restrictions. Image: An official portrait of President Raegan.

The Role of the U.S. Media

American journalists quickly followed up on the Lebanese report. Some reporters had already been investigating U.S. involvement in Nicaragua, particularly the Reagan administration’s covert support for the Contras. These early investigations into Contra funding had raised suspicions, but there had not yet been enough solid evidence to implicate the administration in illegal activities. Now, with the arms sales to Iran exposed, there was an undeniable link that tied the two scandals together.

Investigative reporters, including those at major outlets like The New York Times and The Washington Post, began to delve deeper into the operations. This led to more revelations about how the Reagan administration had circumvented congressional restrictions by using the profits from the arms sales to fund the Contras. The American media’s reporting increased pressure on the Reagan administration to answer for these actions.

The Reagan Administration’s Response

Once the media picked up on the story, the Reagan administration found itself in a precarious position. On November 13, 1986, just ten days after Al-Shiraa’s report, President Reagan addressed the nation, acknowledging that arms had been sold to Iran but denied that they were part of a deal to release hostages. Reagan maintained that the U.S. had not “traded arms for hostages,” a claim that would later be challenged as more details about the operation came to light.

Despite this public denial, cracks began to appear in the administration’s narrative. Reagan’s comments raised more questions than they answered, and the media continued to investigate. The administration struggled to contain the growing scandal, especially as more insiders within the government came forward with information.

Whistleblowers and Congressional Inquiries

Amid growing media scrutiny, members of the Reagan administration and the intelligence community began to leak information to Congress. Whistleblowers, including those involved in the National Security Council (NSC), feared the consequences of the administration’s actions. Among these was Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, a key player in the affair, who had been responsible for overseeing much of the diversion of funds to the Contras.

Congress quickly launched inquiries into the administration’s actions. On November 25, 1986, Attorney General Edwin Meese revealed that, in fact, some of the proceeds from the Iran arms sales had been diverted to fund the Contras. This was a significant admission and marked the first official acknowledgment of the illegal activity at the heart of the scandal.

Soon after, North was fired from his position at the NSC, and his superior, National Security Advisor John Poindexter, resigned. As the scandal widened, Congress began to hold hearings to uncover the full extent of the operation.

Congressional Hearings and the Tower Commission

In response to the mounting public pressure, Congress launched multiple investigations, including highly publicized televised hearings in which key figures involved in the scandal were called to testify. These hearings exposed a broad network of covert operations and secret deals, implicating numerous officials within the Reagan administration.

Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North’s testimony became one of the most memorable moments of the hearings. North admitted to his role in the diversion of funds but claimed he was only following orders to support the administration’s anti-communist agenda.

Simultaneously, President Reagan appointed the Tower Commission in late 1986 to conduct an independent investigation into the affair. Chaired by former Senator John Tower, the commission sought to examine the role of the National Security Council and other federal agencies in the scandal. The Tower Commission’s report, published in February 1987, criticized the Reagan administration for its lack of oversight and control, particularly over the activities of the National Security Council.

The commission concluded that Reagan had not directly authorized the diversion of funds to the Contras but had allowed an environment of “inaction and neglect” to develop within his administration. The report also suggested that Reagan might have been unaware of the full extent of the operation but held him responsible for failing to manage his subordinates effectively.

Independent Counsel and Criminal Investigations

In December 1986, in addition to the Tower Commission, a special prosecutor was appointed to investigate potential criminal actions stemming from the Iran-Contra affair. Lawrence Walsh, the appointed independent counsel, pursued the legal aspects of the case, leading to multiple high-profile indictments.

Oliver North, among others, faced charges of conspiracy, lying to Congress, and destruction of evidence. North was convicted on several charges but later had his convictions vacated on appeal due to legal technicalities, particularly concerning his immunity during testimony. John Poindexter, Reagan’s National Security Advisor, was also convicted but had his convictions overturned.

The independent counsel’s investigation continued for several years, uncovering more evidence of the lengths to which administration officials had gone to conceal their actions. Walsh’s investigation resulted in the indictment of several top officials, including Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger, whose notes and testimonies revealed important details about the affair. However, in the final days of President George H.W. Bush’s term, Weinberger and several others were pardoned, preventing further legal ramifications.

While the Tower Commission and subsequent investigations criticized the Reagan administration for its lack of oversight, President Reagan himself was never directly implicated in authorizing the diversion of funds. Image: President Reagan (center) receives the Tower Commission Report in the Cabinet Room. Seated at the left is John Tower, leader of the Tower Commission.

Reagan’s Televised Apology and Impact on His Presidency

As investigations into the Iran-Contra affair deepened, President Reagan’s popularity took a hit. By early 1987, public trust in Reagan had declined due to the scandal and the administration’s failure to explain its actions clearly. To address the growing public dissatisfaction, Reagan delivered a televised address on March 4, 1987, in which he took full responsibility for the affair. He admitted that “what began as a strategic opening to Iran deteriorated, in its implementation, into trading arms for hostages.”

Despite this admission, Reagan stopped short of acknowledging personal involvement in the diversion of funds to the Contras. Nevertheless, his speech, in which he appeared genuinely regretful, helped to mitigate some of the damage to his presidency. Reagan’s approval ratings, which had plummeted in the wake of the scandal, gradually recovered as the investigations wound down.

The Iran-Contra affair remains a significant event in U.S. political history, as it highlighted the tensions between executive authority, congressional oversight, and the use of covert operations in foreign policy. The scandal underscored the dangers of circumventing the checks and balances built into the U.S. political system and raised questions about accountability at the highest levels of government.

Questions and Answers on the Iran-Contra Affair

What exactly was the Iran-Contra affair?

The Iran-Contra affair was a political scandal during Ronald Reagan’s second term as president (1981-1986). It involved senior U.S. officials secretly selling arms to Iran, a country under an arms embargo, and illegally diverting the profits to fund the Contras, a rebel group fighting the socialist Sandinista government in Nicaragua. This violated the Boland Amendment, which prohibited further U.S. funding of the Contras.

Why were arms sold to Iran during the affair?

Officially, the arms were sold to Iran as part of an effort to secure the release of seven American hostages held by Hezbollah in Lebanon. The Reagan administration hoped that by selling arms to Iran, a country with influence over Hezbollah, they could facilitate the hostages’ release.

What role did Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North play in the scandal?

Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, a National Security Council officer, orchestrated the diversion of profits from the arms sales to Iran to fund the Contras in Nicaragua. He claimed that this idea was suggested by Manucher Ghorbanifar, an Iranian arms dealer. North’s role in facilitating this illegal activity became a central part of the scandal.

Image: A 2010 photo of Oliver North.

Did President Reagan know about the arms-for-hostages deal and the diversion of funds?

While President Reagan was a strong supporter of the Contra cause, evidence is unclear whether he personally authorized the diversion of funds. Handwritten notes from Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger suggest Reagan was aware of arms sales to Iran and the potential for hostage releases. However, Reagan later denied trading arms for hostages and claimed no knowledge of the illegal diversion of funds.

What happened after the scandal was revealed?

After the arms sales were exposed in November 1986, Reagan publicly acknowledged the transfers but denied that the U.S. traded arms for hostages. Following further investigations, he admitted in March 1987 that the arms-for-hostages arrangement had occurred. Several documents related to the scandal were destroyed, complicating the investigation.

What were the outcomes of the investigations?

The Iran-Contra affair was investigated by Congress and the Tower Commission, but neither found conclusive evidence that Reagan knew the full extent of the operation. Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh conducted a criminal investigation, leading to indictments of several officials, including Defense Secretary Weinberger. Eleven convictions resulted, though many were later overturned on appeal.

Were those involved in the scandal pardoned?

In the final days of George H. W. Bush’s presidency, all remaining officials indicted or convicted in connection with the Iran-Contra affair were pardoned. Bush, who had been vice president during the affair, faced criticism from Independent Counsel Walsh, who suggested the pardons were intended to prevent further legal implications for Bush and other senior officials.