What was the Committee of Union and Progress?

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), known in Ottoman Turkish as İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, was a political organization active from 1889 to 1926.

Summary

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) was one of the most influential political entities during the twilight years of the Ottoman Empire.

Active between 1889 and 1926, the CUP began as a secret society founded by medical students and eventually transformed into a wide-reaching political party that reshaped the empire’s final decades. While it initially advocated constitutionalism, liberal reforms, and modernization, the CUP later orchestrated dictatorial rule and orchestrated genocidal campaigns against Christian minorities.

Beyond merely ending the absolute monarchy of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, the CUP would become an unrivaled force in Ottoman politics, ushering in significant governmental transitions, influencing World War I alliances, and leaving a contested legacy in the Republic of Turkey. This explanation outlines the CUP’s emergence, ideological shifts, consolidation of power, and ultimate downfall.

Despite early persecution by the autocratic Hamidian regime (1876–1909), the CUP was able to cultivate extensive networks of supporters both within the empire and among émigrés in Europe. Following a series of failed insurrections, splits, and exiles, CUP operatives capitalized on dissatisfaction in Ottoman Macedonia, guiding the 1908 Young Turk Revolution. Thereafter, the organization alternated between clandestine maneuvering and direct governmental control, consistently centralizing power and pushing for reforms.

Emblem of Committee of Union and Progress.

Over time, it drifted from its initial constitutional ideals toward an exclusionary nationalist agenda. During World War I, the CUP’s leaders—famously known as the Three Pashas—secured a German alliance and pursued policies that devastated the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian communities, contributing to tragic chapters of ethnic cleansing.

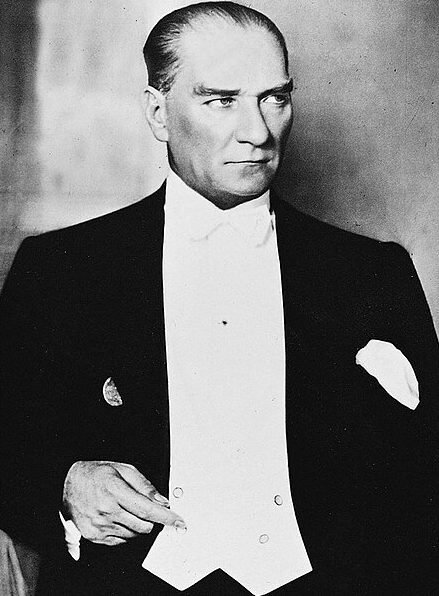

After the empire’s defeat, the CUP formally dissolved, but many of its members continued their political careers under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s new republic, influencing Turkish politics well into the twentieth century.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Origins and Formation

In 1889, a group of students at the Imperial Military School of Medicine in Constantinople (Istanbul) founded a secret society called the Committee of the Ottoman Union. These young reformists, inspired by Enlightenment ideals, sought to reinstate the constitution that Sultan Abdul Hamid II had suspended in 1878. They believed that constitutionalism would revitalize a weakening empire confronted with staggering debts, uprisings by non-Muslim populations, and the burden of foreign intervention. Early on, the sultan’s regime underestimated this youthful circle, dismissing them as an innocuous student group.

The CUP was founded on February 6, 1889, as the Committee of the Ottoman Union (İttihad-ı Osmanî Cemiyeti) by students at the Imperial Military School of Medicine in Constantinople.

Their existence became more precarious when they attempted a coup in 1896, resulting in arrests, exiles, and deep internal divisions. During these exilic years, various factions formed, with some prioritizing liberal reform and others championing more radical measures. These émigré intellectuals and officers, scattered in major European cities, collectively laid the foundation for what would eventually evolve into the CUP.

By forging ties with Freemasons, journalists, and disaffected Ottoman bureaucrats, the group managed to survive political crackdowns. As they rebranded themselves the Committee of Union and Progress, they unified under the shared cause of restoring constitutional rule, even if they still squabbled over strategy and ideology.

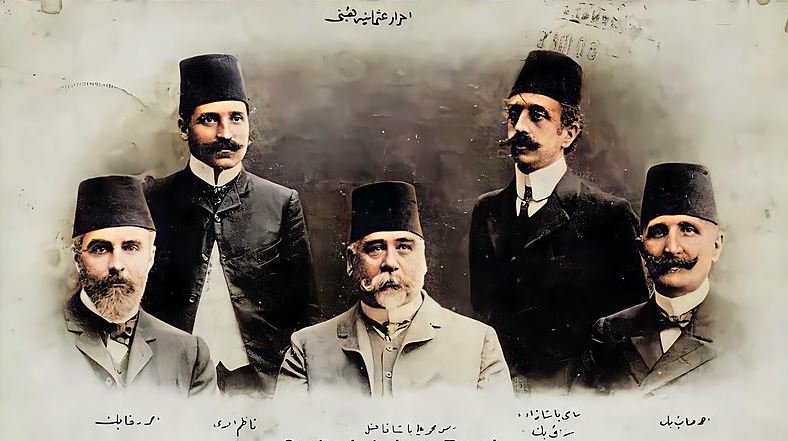

Emerging as part of the Young Turk movement, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) played a significant role in the late Ottoman Empire. It transitioned from a secret revolutionary group to a ruling political force. Image: The Committee of Union and Progress (Young Turks) in 1909.

Revival in Ottoman Macedonia

The reemergence of the CUP at the start of the twentieth century was closely tied to events in Ottoman Macedonia, a region rife with conflict among Bulgarian, Greek, Serbian, and other armed factions. Local Ottoman officers, exasperated by the incessant violence and foreign meddling, began to see the restoration of the constitution as a solution. Secret societies multiplied among junior officers, who believed that guaranteeing rights for all communities within a constitutional framework would restore peace.

By 1906, the Ottoman Freedom Committee had emerged in Salonica (Thessaloniki), eventually merging with the CUP’s Paris-based branch. Talât Bey (later Talât Pasha), an influential local official, became the movement’s leading strategist. A dedicated network of conspirators formed across Rumelia (Ottoman Europe), recruiting officers, bureaucrats, and intellectuals determined to overthrow Abdul Hamid II.

Emulating the clandestine methods of nationalist and revolutionary organizations in the Balkans, the CUP’s “komitecilik,” or rule by secret committee, expanded. Recruits swore unwavering loyalty to the leadership, with disobedience punishable by death. The stage was set for the biggest upheaval the empire had seen in decades.

The 1908 Young Turk Revolution

In 1908, fears arose that foreign powers, especially Britain and Russia, might partition Ottoman Europe under the pretext of protecting Christian minorities. Rumors that the Great Powers were on the verge of dismantling what remained of the empire galvanized pro-constitution Ottoman officers. Two leading revolutionaries, Enver Bey (later Enver Pasha) and Ahmed Niyazi, mobilized militias in the hinterlands of Macedonia, demanding the restoration of the 1876 Constitution.

Initially, Abdul Hamid attempted to negotiate. However, the mutinous Third Army threatened to move directly on Constantinople, and rebellious fervor spread to other units. Confronted with insurrection, Abdul Hamid II capitulated on July 24, 1908, reinstituting the constitution and reconvening the parliament. In a moment of euphoria, crowds celebrated across the empire, believing this “Young Turk Revolution” would herald an era of liberty, equality, and fraternity for Ottoman citizens of all backgrounds.

The CUP, having orchestrated the revolution, gained considerable moral authority, yet it chose not to depose the sultan immediately, focusing instead on influencing governance from the shadows.

Young Turk Revolution Declaration – Armenian, Greek Orthodox & Muslim religious leaders

Second Constitutional Era and Political Rivalries

Following the revolution, the empire entered a period now known as the Second Constitutional Era (1908–1918). The CUP emerged as a formidable bloc within the newly elected parliament after the 1908 elections. However, the party struggled to reconcile its revolutionary methods with its professed commitment to liberal governance. Although it championed modernization—expanding infrastructure, education, and administrative centralization—it also stifled dissent and routinely meddled in ministries.

Their principal rival was the Freedom and Accord Party (also called the Liberal Entente), representing a more decentralized outlook. While Freedom and Accord included conservatives, provincial notables, and minority representatives seeking autonomy, the CUP favored a highly centralized, Turkish-dominated state.

Tensions grew as each side accused the other of plotting coups. In 1909, an attempted counterrevolution, known as the 31 March Incident, threatened to restore Abdul Hamid’s absolutism. The CUP mobilized the “Action Army,” deposed the sultan, and solidified its influence. Yet even after this victory, the CUP’s authority did not go uncontested, and behind-the-scenes machinations continued to shape the empire’s turbulent politics.

Ascendance to One-Party Dominance

Defeats in foreign conflicts—including the loss of territories in the Balkans—fueled CUP radicalization and nationalist fervor. In the aftermath of the catastrophic First Balkan War (1912–1913), the CUP perceived itself as the empire’s only savior.

With massive Muslim refugee crises, patriotic resentment against European interference, and disillusionment with multi-ethnic coexistence, CUP hardliners leaned toward an aggressive Turkish nationalism.

The 1913 Ottoman coup d’état, known as the Raid on the Sublime Porte, removed the government of Kâmil Pasha, whom the CUP considered overly conciliatory toward European powers. During this coup, War Minister Nazım Pasha was assassinated, and CUP loyalists forced the grand vizier to resign at gunpoint.

A triumvirate, often called the Three Pashas—Talât Pasha (Minister of the Interior), Enver Pasha (Minister of War), and Cemal Pasha (Minister of the Navy)—took effective control. From 1913 to 1918, they governed as a dictatorship, introducing martial law, banning opposition parties, and prosecuting critics. The sultan’s role was minimized, and final authority lay in the CUP’s Central Committee, which directed policy in secrecy.

Entry into World War I

Hoping to retrieve lost Balkan territories and counter Russian expansion, the CUP sought a powerful ally. Although various Ottoman officials favored neutrality, the triumvirate established a secret alliance with Germany. The presence of German advisors in the Ottoman military grew, and the controversial arrival of German warships in Constantinople sealed the empire’s fate. In late October 1914, Ottoman forces bombarded Russian Black Sea ports, effectively dragging the empire into the First World War on the side of the Central Powers.

While it initially championed constitutional reform, the CUP later became a dictatorial regime infamous for its nationalist policies and its role in ethnic genocides during World War I.

At first, the CUP leadership planned bold offensives, such as Enver’s disastrous winter campaign against Russia in the Caucasus. Nonetheless, the Ottomans achieved some surprising successes, notably at Gallipoli, which boosted CUP prestige. Simultaneously, the CUP exploited wartime conditions to suppress domestic opposition. Freedom and Accord leaders were either exiled or forced underground, leaving the CUP unchallenged. Rhetorically, CUP propagandists increasingly invoked jihad and pan-Turanism, envisioning a vast union of Turkic peoples stretching into Central Asia—dreams that proved unrealistic against formidable Russian defenses.

Genocidal Campaigns Against Minorities

Amid wartime chaos, the CUP implemented policies of ethnic homogenization, targeting Christian minorities. Already distrustful of the empire’s non-Muslim communities, the CUP leadership used the pretext of national security to deport Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians en masse from strategic areas. These forced relocations were accompanied by systematic massacres, orchestrated largely through paramilitary formations such as the Special Organization.

While the anti-Greek measures in 1914 were often overshadowed by Germany’s desire to keep Greece neutral, the empire nonetheless expelled or terrorized hundreds of thousands of Greeks from coastal regions. Once war with Russia intensified, Armenian communities became the principal targets.

Beginning in April 1915, intellectuals and community leaders were rounded up in Constantinople, followed by sweeping deportations into Syria’s deserts. These events, recognized by many scholars as the Armenian Genocide, resulted in at least one million deaths through starvation, forced marches, and massacres. Similar atrocities befell Assyrian communities. The CUP’s vision of a Turkish-dominated Anatolia left behind a tragic legacy of dispossession and demographic engineering.

Exile, Trials, and Republican Aftermath

By 1918, the Central Powers were in retreat. The Ottoman Empire’s capitulation at the Armistice of Mudros spelled the end of CUP rule. Talât, Enver, and Cemal fled into exile, aware that Allied powers were poised to hold them responsible for mass atrocities. As a successor administration scrambled to negotiate peace, key CUP figures either vanished or were captured. Several were taken to Malta for war-crimes proceedings. Meanwhile, Armenian revolutionaries from the Dashnak party embarked on Operation Nemesis, assassinating several CUP leaders, including Talât and Cemal, in retaliation for the genocide.

In Constantinople, a series of Ottoman courts martial tried CUP figures for crimes against humanity and wartime aggression. Although a handful were executed or imprisoned, many avoided long sentences.

With Allied and royalist authorities attempting to dismantle CUP networks, some surviving Unionists aligned with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s nationalist movement, seeing it as the best hope for resisting partition and foreign occupation.

Consequently, CUP legacies persisted into the Turkish War of Independence. Once Atatürk formed the Republic of Turkey, many former Unionists joined his single-party government under the Republican People’s Party (CHP). They continued certain modernization initiatives once proposed by the CUP, including secularizing reforms and educational expansions.