The End of Japanese Occupation in Singapore

Japan’s surrender at Singapore marked the end of three years of brutal occupation during World War II. The surrender took place on September 12, 1945, at the Municipal Building (now known as City Hall) in Singapore. Image: The Japanese delegation exits the Municipal Building following the surrender ceremony on September 12, 1945.

On September 13, 1945, British forces, led by Lord Louis Mountbatten, officially accepted the Japanese surrender in Southeast Asia, marking the end of the Japanese occupation of Singapore during World War II.

The surrender was a monumental event, not only because it marked the end of a brutal three-and-a-half-year occupation but also because it catalyzed Singapore’s journey toward self-governance and, eventually, independence.

The Japanese occupation left deep scars on Singaporean society, affecting the local population both emotionally and politically, and highlighted the limitations of colonial rule. The surrender at the Municipal Building (now City Hall) signified the restoration of British control but also marked the beginning of a long path toward Singapore’s autonomy.

The Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942-1945)

The Fall of Singapore

Singapore, known as the “Gibraltar of the East,” was a strategic British stronghold in Asia, guarding the key maritime routes between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. However, in February 1942, after just seven days of fighting, Singapore fell to the Japanese in what Winston Churchill called the “worst disaster” in British military history.

The Japanese occupation of Singapore was part of their larger campaign to control Southeast Asia and secure vital resources during World War II. The British surrender was a massive psychological blow, not just to the people of Singapore, but also to the British Empire, as it demonstrated the vulnerability of its colonies.

Image: Britain surrenders Singapore to Japan. Lieutenant-General Yamashita (seated, third from left) confronts Lt. Gen. Percival (seated, back to camera).

Life Under Japanese Rule

For the people of Singapore, the occupation was a period of severe hardship, marked by widespread atrocities, food shortages, and fear. The Japanese renamed Singapore Syonan-to (“Light of the South”), and imposed their authority with ruthless efficiency.

One of the most notorious events was the Sook Ching massacre, a mass execution of suspected anti-Japanese elements, primarily targeting the Chinese community. It is estimated that between 25,000 and 50,000 people were killed during the operation, leaving a legacy of trauma that endures in Singapore’s collective memory.

In addition to violence and repression, the Japanese occupation brought about economic difficulties. Food and medical supplies became scarce, and the local population was subjected to forced labor, conscription, and military duties.

The introduction of Japanese currency, known as “banana money,” further worsened the economy, leading to rampant inflation. By the end of the occupation, Singapore’s infrastructure was in ruins, and the population had suffered immense psychological and material losses.

The Surrender: September 13, 1945

The Road to Surrender

Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, brought an end to World War II in the Pacific. However, the formalities of surrender in Southeast Asia, including Singapore, took several weeks to organize. The British planned a careful and symbolic reoccupation of Singapore, with Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Supreme Allied Commander of Southeast Asia, overseeing the operation.

Mountbatten’s strategy was to reassert British authority and begin the process of rebuilding the city. By the time of the formal surrender on September 13, Singapore had been without effective government for weeks, and the local population was eager for stability.

The Formal Surrender Ceremony

The formal surrender took place at the Municipal Building in Singapore, where General Itagaki Seishiro, representing the Japanese forces in Southeast Asia, signed the surrender documents. In the presence of Mountbatten and other Allied military leaders, the Japanese surrender marked the end of three and a half years of brutal occupation.

The ceremony was steeped in symbolism, emphasizing the restoration of British control and the military defeat of Japan. The Union Jack was raised once again, and Mountbatten gave a speech that signaled the return of order and the start of rebuilding efforts. For many Singaporeans, the surrender represented the end of a dark chapter in their history, and there was a sense of relief and hope that life would soon return to normal.

Post-Occupation Singapore: Relief and Reconstruction

Image: A cheering crowd greets the return of British forces on September 5, 1945.

Initial Reactions to British Return

The return of British forces was met with mixed reactions. On the one hand, there was widespread relief that the Japanese occupation had ended and that a more stable administration was being restored. The British immediately set about restoring law and order, reopening schools, reestablishing the civil service, and initiating reconstruction efforts to repair the infrastructure damaged during the war.

However, the occupation had also shattered the illusion of British invincibility. Many Singaporeans had seen firsthand the failure of the colonial government to defend them against the Japanese and had suffered under the brutal regime that followed. This experience fostered a growing desire for greater self-determination and independence.

Economic and Social Recovery

In the aftermath of the Japanese surrender, Singapore faced significant challenges. The economy had been severely weakened, and many of the city’s buildings, roads, and utilities were in disrepair. Food shortages persisted, and many people remained displaced. The British Military Administration (BMA) took charge of the recovery efforts, focusing on rebuilding essential services, restoring water and electricity, and clearing the streets of debris.

The return of British rule also meant a return to pre-war policies in some areas. However, the experiences of the occupation had changed the political landscape, and many Singaporeans—particularly the Chinese community—were no longer content to accept British rule without question. The seeds of future political movements, calling for independence and self-government, began to take root during this period.

The Sook Ching Massacre and Its Legacy

The Atrocities of the Japanese Occupation

One of the most horrific aspects of the Japanese occupation was the Sook Ching massacre, which targeted suspected anti-Japanese individuals, particularly from the Chinese community. The massacre was carried out between February and March 1942, shortly after the Japanese took control of Singapore. Men between the ages of 18 and 50 were rounded up, interrogated, and executed. The killings took place in various locations across Singapore, including Changi Beach and Punggol Beach.

The full scale of the massacre remains unclear, but estimates of the number of victims range from 25,000 to 50,000. The Sook Ching massacre left an indelible mark on Singapore’s history, and the trauma it inflicted would resonate for generations.

Post-War Trials and Accountability

In the years following the end of World War II, Allied forces sought to bring Japanese war criminals to justice. General Tomoyuki Yamashita, the commander of the Japanese forces during the invasion of Singapore, was tried for war crimes, including his involvement in the Sook Ching massacre. He was found guilty and executed in 1946.

However, many of the individuals responsible for the massacre escaped justice, and the event remains a source of deep historical pain for Singaporeans. In modern Singapore, memorials and museums commemorate the victims of the massacre, ensuring that the horrors of the occupation are not forgotten.

The Path Toward Independence

Political Awakening in Singapore

The Japanese occupation was a turning point in the political consciousness of the people of Singapore. Before the war, there had been limited calls for self-rule, and the British colonial government maintained tight control over the political system. However, the war exposed the vulnerability of colonial powers and the inability of the British to protect their colonies from external threats.

In the post-war years, a growing nationalist movement began to emerge in Singapore. The return of British rule was initially accepted as a temporary measure to restore order, but many Singaporeans began to push for greater political representation and autonomy. This led to the formation of political groups and labor unions that advocated for self-government.

Steps Toward Self-Governance

In 1946, Singapore became a separate Crown Colony, no longer administered as part of the Straits Settlements, which had included Malaya. This shift marked the beginning of a more direct British administration, but it also laid the groundwork for future demands for self-rule.

By the 1950s, political movements such as the People’s Action Party (PAP), founded by Lee Kuan Yew, gained momentum, pushing for greater autonomy and eventually independence. In 1959, Singapore achieved self-government, with Lee Kuan Yew becoming its first Prime Minister. However, full independence would come later, following a brief and tumultuous period of union with Malaysia.

The Civilian War Memorial in War Memorial Park, Beach Road, symbolizes Singapore’s four major races: Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Eurasian.

The Road to Independence in 1965

Merger with Malaysia and Separation

Singapore’s path to full independence took a complex turn in the early 1960s, when the island joined with Malaysia in a political union. The merger, which took place in 1963, was seen by both the British and Singaporean leadership as a way to secure Singapore’s economic and political future. However, deep-rooted cultural and political differences between Singapore and the rest of Malaysia soon surfaced.

By 1965, tensions between the predominantly Chinese Singapore and the Malay-majority Malaysian government had reached a breaking point. On August 9, 1965, Singapore was expelled from Malaysia and became an independent nation. This moment, although fraught with uncertainty, marked the beginning of Singapore’s transformation into a sovereign state.

The Legacy of the Japanese Occupation

The legacy of the Japanese occupation played a significant role in shaping Singapore’s post-war political identity. The occupation exposed the fragility of colonial rule and galvanized a generation of Singaporeans who sought a future free from foreign domination. The suffering endured during the occupation, particularly during events like the Sook Ching massacre, left a lasting imprint on Singapore’s collective memory and contributed to the desire for self-determination.

Conclusion

The Japanese surrender on September 13, 1945, marked the end of one of the darkest periods in Singapore’s history and the beginning of a new chapter in the island’s development. While the return of British forces brought relief and stability to the war-ravaged population, it also signaled the beginning of a shift in Singapore’s political landscape. The occupation had exposed the limitations of colonial rule, and in the years that followed, Singaporeans increasingly sought control over their own destiny.

The events of September 13, 1945, set Singapore on a path toward self-governance, eventual independence, and the development of a modern, prosperous nation. Today, Singapore stands as a testament to the resilience of its people and their ability to overcome the challenges of occupation and colonialism to build a vibrant, independent state.

Questions and Answers

When did the Japanese officially surrender to the Allied Powers, marking the end of World War II?

The Japanese officially surrendered on September 2, 1945, aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

Who accepted the Japanese surrender in Southeast Asia on September 12, 1945?

Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Supreme Allied Commander of Southeast Asia, accepted the Japanese surrender at the Municipal Building in Singapore.

Who were the key Japanese representatives during the surrender aboard the USS Missouri?

The Japanese delegation included Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, General Yoshijiro Umezu, and nine other representatives from the Japanese government, navy, and army.

Japanese foreign affairs minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signs the Japanese Instrument of Surrender aboard the USS Missouri as American General Richard K. Sutherland watches, 2 September 1945.

What request did the Japanese delegation make regarding the signing of the Instrument of Surrender, and was it accepted?

The Japanese requested to sign “on behalf of the Emperor” in accordance with the Japanese constitution, but this request was denied.

Which Allied representative signed the Instrument of Surrender on behalf of the Allied Powers?

General Douglas MacArthur signed the Instrument of Surrender on behalf of the Allied Powers.

Who were some of the other Allied representatives who signed the surrender aboard the USS Missouri?

Representatives included Admiral C. W. Nimitz for the U.S., Admiral B. Fraser for Britain, and General T. A. Blamey for Australia.

What role did General MacArthur play after the Japanese surrender?

MacArthur oversaw the occupation of Japan, which lasted until 1952. During this period, many high-ranking Japanese officials were tried for war crimes.

The 5th Indian Division marches through the streets shortly after arriving as part of the reoccupation force.

What happened during the surrender ceremony in Singapore on September 12, 1945?

Lord Mountbatten inspected the Guards-of-Honour from various Allied forces while a band played “Rule Britannia” and the Royal Artillery fired a 17-gun salute. General Itagaki signed the surrender on behalf of Field Marshal Count Hisaichi Terauchi.

Why did Field Marshal Count Hisaichi Terauchi not attend the Singapore surrender ceremony?

Terauchi was unable to attend due to illness after suffering a stroke.

What notable items did Field Marshal Terauchi later surrender to Mountbatten in Saigon?

Terauchi surrendered two swords: a 16th-century short sword and a 13th-century long sword.

How many copies of the Instrument of Surrender were signed during the ceremony in Singapore?

A total of 11 copies were signed, including one for each Allied nation, King George VI, and the South East Asia Command.

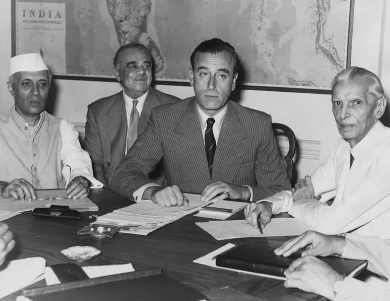

Lord Mountbatten meeting with Nehru and Jinnah

Who witnessed the surrender ceremony in Singapore?

The ceremony was witnessed by 400 spectators, including Allied commanders, community leaders, and former prisoners of war.

What was significant about the Union Jack used during the surrender ceremony in Singapore?

The Union Jack raised at the ceremony was the same flag that had flown over Government House before the war and had been hidden by Mervyn Cecil Frank Sheppard during his imprisonment at Changi Prison.