Amasa J. Parker: Life and Career

Amasa Junius Parker’s life and career were marked by a deep commitment to law, education, and public service. From his early years as a teacher and lawyer to his tenure as a judge and political figure, Parker made enduring contributions to the state of New York and the country. His legacy continues to be remembered in legal, educational, and public service circles.

Early Life and Education

Amasa Junius Parker was born on June 2, 1807, in Sharon, Connecticut. His parents, Reverend Daniel Parker, a Congregational minister, and Anna (Fenn) Parker, played significant roles in his early development. His father, in addition to his ministerial duties, also worked as a teacher in various locations, including Greenville, New York. This intellectual environment no doubt influenced Parker’s academic pursuits.

In 1816, when Parker was just nine years old, his family moved to Hudson, New York. There, his education was primarily managed by his father, supplemented by instruction from private tutors. By the age of 16, Parker’s academic prowess had advanced to the point that he was hired as both a teacher and the principal of Hudson’s academy, a notable position for someone so young. He held this role from 1823 until 1827, establishing a foundation for his lifelong dedication to education.

While teaching, Parker took a major step forward in his education. In 1825, he underwent a rigorous comprehensive examination at Union College. This examination covered the entire four-year curriculum, a feat of intellectual rigor that Parker passed with ease. The college awarded him a degree, classifying him as part of that year’s graduating class, even though he had not attended the college in a traditional manner. His performance in this examination was a testament to his intelligence and discipline, and it marked the beginning of his formal legal education.

Legal Training and Early Career

In 1827, Parker transitioned into the legal profession. He initially studied law under the tutelage of John W. Edmonds, an attorney with whom he had a close professional relationship. To further refine his legal skills, he completed his studies in Delhi, New York, under the guidance of his uncle, Amasa Parker, a respected lawyer in the area. Parker’s admission to the bar came in 1828, and he immediately entered into legal practice with his uncle.

Parker’s early legal career flourished in Delhi. He quickly built a solid reputation, practicing law across several counties in New York. His work brought him into frequent contact with both state circuit and chancery courts, expanding his influence and gaining recognition within legal circles. He handled various legal matters, helping to establish a successful and respected legal practice. His ability to navigate complex legal terrain set him on a path toward public service.

Political Career Begins

Parker’s rise to political prominence began with his election as District Attorney of Delaware County in 1833, a position he held until 1836. His effectiveness as a prosecutor garnered attention, and he quickly became a trusted figure in local politics. The Democratic Party, with which Parker was affiliated, saw his potential early on. In 1834, he was elected to the New York State Assembly, representing Delaware County. Serving in the 57th New York State Legislature, Parker began to make his mark in the state’s legislative body.

Parker’s legal and political acumen was further recognized when, in 1834, he was elected as a regent of the University of the State of New York. At the time, he was the youngest individual ever to serve on the board, a clear indicator of his growing influence. His tenure as a regent lasted from 1835 to 1844, during which time he remained deeply involved in shaping New York’s educational policies.

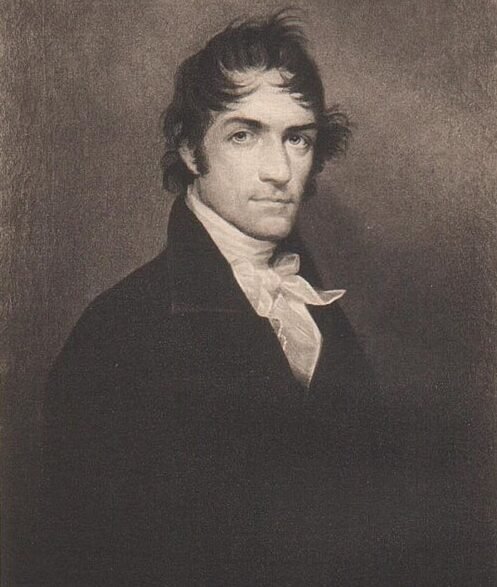

Image: A picture of Parker.

U.S. Congress and National Politics

Parker’s political career reached the national stage in 1837 when he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Representing Delaware and Broome counties, he served in the 25th Congress from 1837 to 1839. During his tenure in Congress, Parker supported President Martin Van Buren and his Democratic administration. He focused on key issues of the time, including the Independent Treasury Bill, which Van Buren championed but initially failed to pass. The bill was designed to create a system independent of state and private banks for handling government funds, a critical issue in the post-Jacksonian economic landscape.

Parker was also involved in discussions related to the Mississippi election case, which saw two Democratic House members replaced by Whigs. Additionally, he worked on issues concerning the operations of the U.S. General Land Office and its processes for disposing of public land, a hot topic as the U.S. continued to expand westward. Parker was engaged in the political debates of the time, including the aftermath of the fatal duel between Congressman Jonathan Cilley and William J. Graves, which captured national attention.

Despite Parker’s active role in Congress, he chose not to seek re-election after his first term, returning instead to his legal practice in New York. However, his foray into national politics had raised his profile significantly.

Judicial Career and the Anti-Rent War

In 1844, Parker moved to Albany, New York, after being appointed judge of the Third Circuit of the New York State Circuit Courts. This judicial appointment proved to be a defining period in his career. As a circuit court judge, Parker presided over several critical cases, including the trial of Smith A. Boughton, a leader in the Anti-Rent War. The Anti-Rent War was a conflict between tenants and large landowners in upstate New York, sparked by the remnants of the old feudal-like manor system. Parker’s handling of the trial became controversial when he declared a mistrial, necessitating a retrial under another judge, John W. Edmonds. Ultimately, Boughton was convicted and sentenced to life in prison, though his sentence was later commuted.

In 1847, Parker was elected to the New York Supreme Court, where he served until 1855. His judicial service also extended to the New York Court of Appeals in 1854, as one of the ex officio judges. One of his most significant rulings came in the Snedeker v. Warring case, which involved whether a large ornamental statue on a country estate should be classified as real property or personal property. Parker ruled that the statue was real property, a decision that was upheld by a 5-2 vote in the Court of Appeals. This case became a landmark in the field of fixtures law, helping to clarify legal distinctions in property classification.

Return to Law and Political Candidacies

After his Supreme Court tenure ended in 1855, Parker returned to private law practice. He established a law firm in Albany, partnering with his son, Amasa J. Parker Jr., and former judge Edwin Countryman. During this phase of his career, Parker took on high-profile cases, including one that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. He successfully argued that national banks were subject to state taxation, marking another important victory in his legal career.

In addition to his legal work, Parker was instrumental in founding Albany Law School in 1851. He served as a faculty member for over twenty years, helping to train future generations of lawyers.

Despite his focus on legal practice, Parker remained politically active. He ran twice for governor of New York on the Democratic ticket, in 1856 and 1858. However, both campaigns were unsuccessful; he lost to John Alsop King in 1856 and Edwin D. Morgan in 1858. His losses reflected the growing strength of the newly formed Republican Party in the state during the tumultuous pre-Civil War period.

Civil War and Later Career

As tensions over slavery and states’ rights intensified leading up to the Civil War, Parker remained loyal to the Democratic Party, advocating a moderate approach in the hope that compromises might prevent bloodshed. When the war broke out in 1861, Parker supported the Union cause but was critical of certain actions by President Abraham Lincoln’s administration, particularly concerning civil liberties. In 1864, Parker successfully argued in Palin v. Murray, a case about false imprisonment by federal authorities, securing a favorable judgment for his client. The case was later moved to federal court, where the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the decision in favor of the plaintiff in 1869.

In 1867, Parker was a delegate at the New York State Constitutional Convention. His contributions to this convention were substantial, especially his advocacy for court reforms, including the abolition of chancery courts and the merging of law and equity powers within the same courts. This marked a significant modernization of New York’s legal system.

Parker continued to practice law into his later years, though he took on fewer criminal defense cases. One notable exception was his defense of George W. Cole in 1868, in which Parker secured an acquittal for Cole on the grounds of temporary insanity. Despite his success in this case, Parker declined lucrative offers, including a substantial retainer to represent William “Boss” Tweed during his corruption trials, reflecting his principled approach to law.

Contributions to Education and Public Service

Throughout his career, Parker remained deeply committed to education and public service. In addition to his work at Albany Law School, he served as a trustee of several educational institutions, including Union College, Cornell University, Albany Medical College, and Albany Female Academy. His advocacy for mental health care led him to champion the creation of a state hospital for the insane. He was eventually appointed to the board of trustees for the Hudson River State Hospital, a position he held until 1881.

Parker’s involvement in public service extended beyond education and law. After the death of Harmanus Bleecker, a prominent Albany philanthropist, Parker helped manage Bleecker’s estate. His work led to the construction of the Harmanus Bleecker Hall, a library and theater complex, which laid the foundation for the Albany public library system.

Later Life and Legacy

Parker continued to practice law well into his old age, arguing his final case before the New York Court of Appeals just a week before his death. On May 13, 1890, Amasa J. Parker passed away in Albany, New York. He was laid to rest in Albany Rural Cemetery.

Parker’s legacy is multifaceted. He contributed significantly to New York’s legal system through his judicial rulings, legal practice, and educational efforts. His work as a regent and trustee for numerous educational institutions left a lasting impact on higher education in the state. His involvement in public service, from promoting mental health care to advocating for court reforms, further underscores his dedication to improving society. Parker’s influence extended to his family as well; his son, Amasa J. Parker Jr., and daughter Mary Parker, who married Erastus Corning, both carried on his legacy of public service.

His letters to his wife

On December 31, 1837, Amasa J. Parker sat in his quarters at Mrs. Pittman’s boarding house in Washington, D.C., writing a letter to his wife, who was home in Delhi, New York.

Parker included a seating chart of Mrs. Pittman’s regular diners, which featured future presidents Millard Fillmore of New York and James Buchanan of Pennsylvania.

The Amasa J. Parker Papers (1836-1875) contain more than sixty letters Parker wrote to his wife during his 1837-1839 congressional term. His frustration over being far from home during his wife’s illness may have influenced his decision not to seek reelection.

At the end of his term, Parker returned to Delhi, resumed his law practice, and continued his political career within New York State. He later became a circuit judge in Albany and one of the founders of Albany Law School.

Questions and Answers about Amasa Junius Parker

When and where was Amasa Junius Parker born?

Amasa Junius Parker was born on June 2, 1807, in Sharon, Connecticut.

Who were Amasa Junius Parker’s parents?

Parker’s parents were Anna (Fenn) Parker and Reverend Daniel Parker, a Congregational minister and teacher.

Where did Parker receive his early education?

Parker received his early education from his father and private tutors. He later worked as a teacher and principal at Hudson’s academy before attending Union College, where he earned his degree in 1825.

How did Amasa Junius Parker become a lawyer?

Parker studied law under attorney John W. Edmonds and later completed his legal training in the office of his uncle, Amasa Parker, in Delhi, New York. He was admitted to the bar in 1828.

What legal and political roles did Parker hold in Delaware County, New York?

Parker was elected District Attorney of Delaware County in 1833, serving until 1836. He also represented Delaware County in the New York State Assembly in 1834.

When did Parker serve as a U.S. Representative, and what were some of the key issues he worked on?

Parker served as a U.S. Representative from 1837 to 1839. He worked on significant issues, such as supporting President Martin Van Buren’s Independent Treasury bill and addressing matters related to public land sales.

What was Parker’s role in the founding of Albany Law School?

Parker helped found Albany Law School in 1851 and served on its faculty for over two decades.

What was Parker’s position on slavery and the Civil War?

Before the Civil War, Parker remained loyal to the Democratic Party and advocated for a moderate stance on slavery, hoping to avoid conflict. Once the war began, he supported the Union but was critical of some of the Lincoln administration’s policies.

Did Parker take on criminal defense cases?

Yes, in 1868, Parker successfully defended George W. Cole, securing an acquittal based on temporary insanity after Cole was charged with murder.

What were Parker’s contributions to education and public institutions?

Parker was a trustee of Union College, Cornell University, and Albany Medical College. He also advocated for the establishment of a state hospital for the insane and served as a trustee of the Hudson River State Hospital.

Parker was involved in managing the estate of Harmanus Bleecker, which led to the construction of Harmanus Bleecker Hall, a library and theater complex. This later contributed to the development of Albany’s public library system. Image: Harmanus Bleecker (1779 – 1849).

When did Parker die, and where is he buried?

Amasa Junius Parker died on May 13, 1890, in Albany, New York. He is buried in Albany Rural Cemetery.

Who was Amasa Junius Parker’s wife, and who were their notable children?

Parker married Harriet Langdon Roberts on August 27, 1834. They had several children, including Amasa J. Parker Jr., and Mary Parker, who married Erastus Corning.