Life and Major Works of Jupiter Hammon, the founder of African-American Literature

Jupiter Hammon is widely regarded as the founder of African-American literature, owing to his landmark status as the first Black poet to be published in North America. His life, however, remains only partially documented, but through his writings, one can glimpse his intellectual insights, spiritual dedication, and nuanced views on the institution of slavery.

Born into slavery in the early 18th century, Hammon lived his entire life on Long Island, New York, serving the Lloyd family, a prominent family known for their wealth and influence. Over the years, he emerged as an educated and respected poet, preacher, and clerk, producing a small but impactful body of work that has resonated with readers for its subtle criticism of slavery and powerful religious themes.

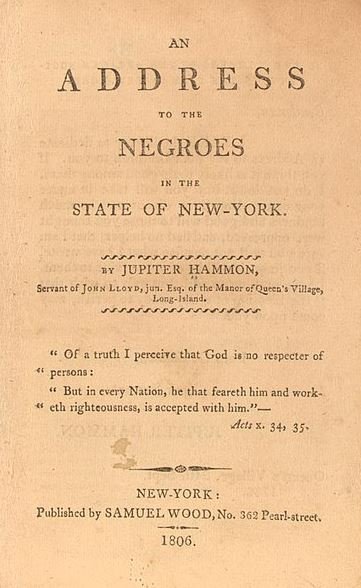

Jupiter Hammon (October 17, 1711 – c. 1806) is recognized as a pioneering figure in African-American literature. Image: An address by Hammon to the Negros in New York.

Early Life and Background

Jupiter Hammon was born on October 17, 1711, at Lloyd Manor, a large estate on Long Island owned by the Lloyd family. His parents, Opium and Rose, were also enslaved by the Lloyds and were among the earliest recorded enslaved people on the estate. The Lloyds, particularly Henry Lloyd, were involved in mercantile business, and their family amassed considerable wealth, which enabled them to sustain their large estate and employ several enslaved people.

Unlike many enslaved individuals of his time, Hammon was granted an opportunity to learn to read and write. His education was facilitated through the Anglican Church’s Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, which sought to educate and convert enslaved people and Indigenous Americans. The Lloyds likely supported Hammon’s education for both practical and religious reasons. Literacy and writing skills could make him more valuable to their business endeavors, especially in clerical capacities. Hammon ultimately became a commercial clerk, assisting the Lloyds in managing their affairs. His literacy also empowered him to write, giving him a unique voice among African Americans of his era and allowing him to engage intellectually with themes of spirituality and morality.

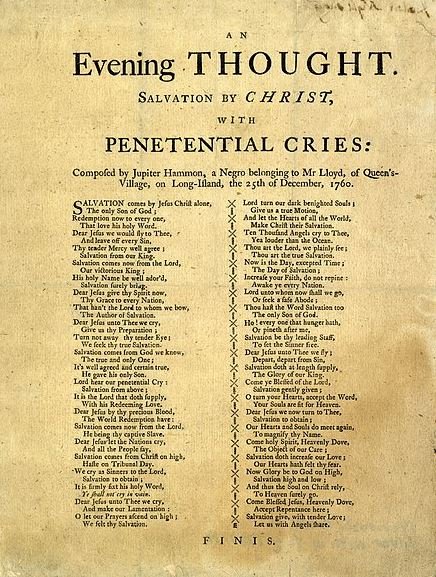

Literary Debut: An Evening Thought

Hammon’s first known work, An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ, with Penitential Cries, was composed on December 25, 1760, and published in 1761. This work made him the first Black poet published in North America. Written as a broadside, the poem is deeply religious, reflecting Hammon’s strong Christian faith. It speaks to his sense of humility and dedication to salvation through Jesus Christ. The poem does not explicitly reference his condition as an enslaved person, but it is suffused with a sense of penitence and devotion, perhaps reflecting an inward hope for spiritual freedom despite his physical bondage.

In this poem, Hammon emphasizes themes of salvation and divine forgiveness, which may have resonated with his enslaved audience and other African Americans. Hammon’s profound religious beliefs shaped his worldview, and his faith provided him a platform to express his thoughts in ways that subtly critiqued the injustices around him. Although An Evening Thought did not confront slavery directly, it established him as a literate and eloquent African-American voice and laid the groundwork for his future writings.

An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley

Eighteen years after the publication of his first poem, Hammon wrote An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley, a poem dedicated to Phillis Wheatley, the first published African-American female poet. Although Hammon and Wheatley never met, he admired her achievements. Wheatley had risen to prominence after her poetry was published in London in 1773, drawing attention to the intellectual potential of enslaved individuals. Hammon’s address to Wheatley is not just a message of admiration but also a spiritual guide for her, encouraging her to continue her Christian journey with humility and faith.

In the poem, Hammon aligns himself with Wheatley’s Christian values and underscores the importance of faith and piety in their shared struggle. The poem comprises 21 quatrains, each paired with a Bible verse, and emphasizes how faith can serve as a source of strength. Hammon’s dedication to Wheatley demonstrates his respect for her accomplishments and his hope that their collective faith could transcend the suffering of their enslaved status. His address to Wheatley has since been regarded as a pivotal moment in African-American literary history, symbolizing solidarity and encouragement between two early Black writers.

Later Works: The Kind Master and Dutiful Servant and A Poem for Children with Thoughts on Death

Following his address to Wheatley, Hammon continued to write, focusing on themes of Christian obedience, morality, and reflections on life and death. In 1778, he published The Kind Master and Dutiful Servant, a poetic dialogue between a master and his enslaved servant. Although it may appear on the surface as a message of compliance, Hammon’s careful wording reveals a nuanced examination of the complexities of the master-servant relationship. This poem reflects Hammon’s internalization of Christian doctrine, portraying a submissive servant and a benevolent master, perhaps as an ideal rather than a reality.

In 1782, Hammon wrote A Poem for Children with Thoughts on Death. Addressed to young readers, this work contains Hammon’s musings on mortality and the importance of living a moral life in preparation for the afterlife. Through religious teachings, he attempts to impart to children the gravity of life choices and the Christian path to salvation. This poem is characteristic of Hammon’s approach, using religion to encourage moral behavior and indirectly emphasizing the endurance and resilience necessary for enslaved people to survive their circumstances.

An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York

Perhaps Hammon’s most significant work is An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York, delivered in 1786 at a meeting of the African Society in New York City. In this address, Hammon is at his most direct in discussing the institution of slavery and its implications for African Americans. He was seventy-six years old and still enslaved at the time, and his words reflect a seasoned perspective on the hardships and moral challenges faced by enslaved people. Hammon acknowledges the cruelty of slavery but encourages his fellow African Americans to maintain their Christian faith as a source of strength.

In this speech, Hammon reassures his audience, saying, “If we should ever get to Heaven, we shall find nobody to reproach us for being black, or for being slaves.” This powerful line reflects Hammon’s belief in spiritual equality, suggesting that while earthly injustice may persist, the afterlife offers a just recompense. His address also subtly advocates for the gradual abolition of slavery. He acknowledges that immediate emancipation is unlikely but expresses a desire for freedom for future generations, especially the younger members of the Black community.

The address became influential in abolitionist circles, as it highlighted the inner life and moral resilience of enslaved people. Hammon’s speech circulated among abolitionists and was published by anti-slavery societies, marking him as an early voice in the movement against slavery.

Rediscovery of Lost Works

In recent years, previously unknown works by Hammon have been discovered. In 2011, a doctoral student found a previously unpublished poem dated 1786 in Yale University’s Manuscripts and Archives library. Scholars believe this work shows a more mature and possibly nuanced view on slavery, suggesting a subtle evolution in Hammon’s perspective. Another poem was uncovered in 2015 by a researcher studying the Townsend family and their enslaved people, hinting at the possibility of further hidden writings by Hammon that may offer more insight into his thoughts.

Legacy and Influence

Jupiter Hammon’s literary contributions, though small in volume, have had a lasting impact on African-American literature and anti-slavery discourse. His writings are deeply infused with Christian morality and biblical references, and his approach to addressing slavery was influenced by his religious beliefs. While some may interpret his works as advocating for submission, a closer reading reveals that Hammon used his literary talents to subtly critique the institution of slavery and offer spiritual solace to other African Americans. His nuanced tone allowed him to address sensitive topics without directly challenging his enslavers, preserving both his voice and his safety in a volatile time.

Hammon’s work bridges the spiritual and the political, showcasing how religious devotion served as both a tool of endurance and a lens through which to critique injustice. His words have inspired later generations of African-American writers, including abolitionists and poets, who found in him an early model of resilience and faith-driven activism. As a founder of African-American literature, Hammon paved the way for future Black authors to express their experiences, shaping the foundation of a rich literary tradition that would grow and evolve over the centuries.

Summary of Major Works

- An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ, with Penitential Cries (1761): Hammon’s first poem, establishing him as the first Black poet published in North America.

- An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley (1778): A poem dedicated to Phillis Wheatley, encouraging her spiritual journey.

- The Kind Master and Dutiful Servant (1778): A poetic dialogue exploring the master-servant relationship.

- A Poem for Children with Thoughts on Death (1782): A reflection on life, death, and moral conduct.

- An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York (1786): Hammon’s most influential work, urging faith and gradual emancipation.

Jupiter Hammon’s legacy endures as a foundational figure in African-American literature, using his voice to bridge the worlds of faith and freedom. His subtle critiques and expressions of resilience continue to resonate, marking him as a pioneer in articulating the complexities of Black life in early America.

Frequently Asked Questions about Jupiter Hammon

Born into slavery at Lloyd Manor on Long Island, Jupiter Hammon learned to read and write, later working as a clerk and preacher. Image: “An Evening Thought”.

What is known about Jupiter Hammon’s early life and family background?

Jupiter Hammon was born into slavery at Lloyd Manor on Long Island, New York, and likely served the Lloyd family his entire life. His parents, Opium and Rose, are believed to have been among the first enslaved people recorded in the Lloyd estate documents.

How did Jupiter Hammon receive an education?

Hammon’s literacy was enabled by the Lloyd family through the Anglican Church’s Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. His education was unusual for an enslaved person and was likely supported by the Lloyds for its practical benefits to their business.

What was the significance of Hammon’s first published work?

Hammon’s first published work, An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ, with Penitential Cries, printed in 1761, made him the first Black poet published in North America. It laid the foundation for his contributions to African-American literature.

What themes did Hammon explore in his writings?

He often addressed Christian morality, obedience, and religious beliefs in his works, which he used to subtly critique slavery. His religious views allowed him to convey complex perspectives on slavery without openly defying the system.

Who was Phillis Wheatley, and what was Hammon’s connection to her?

Phillis Wheatley was an enslaved poet who published her poetry collection in 1773. Although they never met, Hammon admired her work and wrote An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley in 1778 to encourage her on her spiritual journey.

What is An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York about, and why is it significant?

Delivered at the African Society’s inaugural meeting in New York City in 1786, this address expressed Hammon’s views on Christian faith and slavery, hoping for gradual abolition. It became his most influential work, circulating widely among abolitionist groups.

What became of Hammon’s legacy after his final publication?

After his last publication, An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York, Hammon’s life is mostly undocumented. He is believed to have died around 1806 and was likely buried in an unmarked grave on the Lloyd estate.

Have any new works by Hammon been discovered recently?

Two unpublished works by Hammon were discovered recently: one in 2011, a poem suggesting a shift in his views on slavery, and another in 2015, found while researching enslaved populations related to the Townsend family in Oyster Bay.

What is the importance of Hammon’s literary contributions?

Hammon’s writings, often centered around Christian themes and critiques of slavery, positioned him as a pioneering figure in African-American literature and early anti-slavery thought. His unique voice offered a deeply personal perspective on faith and freedom.