Who was Isaac Barré?

Isaac Barré, born on October 15, 1726, in Dublin, Ireland, was a prominent Anglo-Irish soldier and politician whose life and career spanned significant military and political upheavals in the British Empire and its American colonies.

Known for his fierce oratory skills, steadfast loyalty, and advocacy for colonial American rights, Barré played a notable role in both the Seven Years’ War and British parliamentary debates leading up to the American Revolution. His enduring legacy, especially his coining of the term “Sons of Liberty,” reflects his complex and influential position in British-American history.

Early Life and Background

Isaac Barré was born to Peter and Marie Madelaine (Raboteau) Barré, Huguenot refugees who fled religious persecution in France and settled in Ireland. Peter Barré established himself as a linen dealer in Dublin and served as the High Sheriff of Dublin City. This position and the family’s background in trade gave Barré a respectable upbringing.

Encouraged by his parents, he attended Trinity College in Dublin, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1745. While his family hoped he would pursue a career in law, Barré instead chose to enter the British Army, setting the course for a career that would soon distinguish him in military and political fields alike.

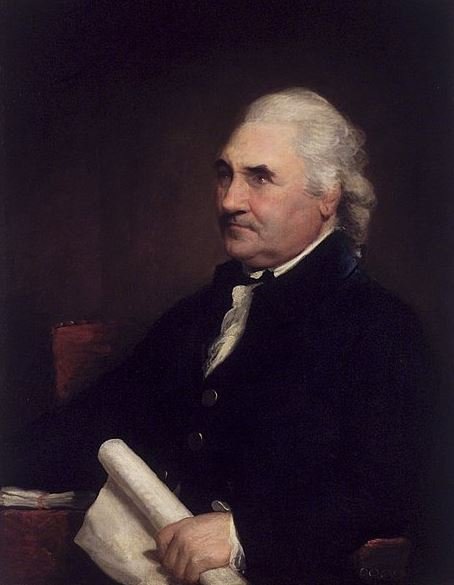

Image: A 1765 portrait of Barré by Hugh Douglas Hamilton.

Military Beginnings and the War of the Austrian Succession

In 1746, Barré joined the British Army’s 32nd Regiment of Foot as an ensign. His initial military experience came during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748), a major conflict over the balance of power in Europe.

During his early years in the military, Barré demonstrated his commitment and began honing his skills, which later led to his rise through the ranks. By 1755, after nearly a decade of service, he had achieved the rank of lieutenant and was promoted to captain the following year.

Service in the Seven Years’ War and French and Indian War

When the Seven Years’ War broke out in 1756, Barré was already an experienced soldier.

His skills and reputation grew as he joined the British forces fighting in North America, where this global conflict became known as the French and Indian War. He served under General James Wolfe, first participating in the failed Rochefort expedition of 1757, which aimed to capture the French port of Rochefort on the Atlantic coast. Although the expedition was unsuccessful, it connected Barré with General Wolfe, who became a crucial influence in Barré’s military career.

Following Rochefort, Barré served with Wolfe in Canada, where he played a significant role in British operations, including the pivotal Siege of Louisbourg in 1758. This siege ended with a British victory and laid the groundwork for their advance into French territories.

The following year, Barré fought in the famous Battle of Quebec in 1759, where Wolfe was killed. During this battle, Barré was severely wounded, taking a bullet to the cheek that left him partially blind and gave him a distinct appearance. He was among the officers who witnessed Wolfe’s final moments, a scene later immortalized in Benjamin West’s renowned painting. Barré’s injury marked him both physically and symbolically, earning him a reputation for valor and sacrifice.

Transition to Politics and Early Parliamentary Career

Returning to England in 1760, Barré hoped his service record and the sacrifices he made in the war would lead to further promotion. However, despite his exemplary service, he was overlooked by William Pitt the Elder, who controlled military appointments at the time. It was then that William Petty, the Earl of Shelburne (later Lord Shelburne), a fellow Irishman and influential political figure, intervened to support Barré’s transition into a political career. Shelburne arranged for Barré to become lieutenant colonel of the newly formed 106th Regiment of Foot in 1761. Furthermore, Shelburne introduced him to British politics, securing him a parliamentary seat in Chipping Wycombe.

Shelburne valued Barré’s military experience and oratory skills, recognizing his potential to serve as a powerful voice in the House of Commons. He positioned Barré as a “bravo,” or a bold voice, to counter William Pitt. Barré’s first speeches in Parliament were directed against Pitt, criticizing his policies with such intensity that they quickly captured public attention. Although his initial opposition to Pitt was fierce, Barré later aligned with him, sharing a growing opposition to Britain’s taxation of its American colonies.

Advocate for American Colonial Rights and the Stamp Act Controversy

Barré became a prominent critic of British policies toward the American colonies, particularly during the heated debates surrounding the Stamp Act of 1765. This act, which imposed a direct tax on the colonies, required that many printed materials in America be produced on stamped paper from Britain. The act sparked widespread resentment, as colonists argued that they were being taxed without representation in Parliament.

In response to a speech by Charles Townshend, who defended the Stamp Act and claimed that the colonies owed their growth and prosperity to British “care and nurture,” Barré delivered one of his most famous speeches. He retorted by arguing that the colonies had grown strong not because of British support, but because of neglect, and had fled British tyranny to build their own communities. During this speech, he referred to the colonists as “Sons of Liberty,” a term that resonated deeply with Americans. It quickly became associated with groups opposing British policies and was adopted as the name of anti-British organizations across the colonies. This phrase, which symbolized resistance to oppression, remains one of Barré’s lasting contributions to American history.

Further Political Roles and Advocacy

Barré’s outspoken support for American colonial rights solidified his role as a significant parliamentary figure. Between 1766 and 1768, he served as Vice-Treasurer of Ireland, and his career in government continued to progress. In 1782, he was appointed Treasurer of the Navy, a position with a considerable pension of £3,200 annually. This pension attracted criticism, especially since the government had recently called for economic restraint.

However, William Pitt the Younger defended the pension, explaining that it compensated Barré for being previously dismissed from his military positions. Barré’s political career reached its zenith when he was appointed Paymaster General of the Forces in 1782, managing the payroll for the British Army.

In 1784, Barré accepted the lucrative position of Clerk of the Pells, responsible for recording all Exchequer income and payments. This sinecure paid him based on a commission structure, allowing him to accumulate considerable wealth. Although the role was largely ceremonial by that time, it granted him financial security and reflected his success in British political circles.

Continued Advocacy for American Causes

Barré’s understanding of North American issues was profound, partly due to friendships with merchants and colonists that kept him informed about the colonies’ economic and social conditions. His insight into colonial grievances and his strong voice against taxation policies positioned him as an influential figure who understood and empathized with the American cause. Alongside other notable figures, Barré opposed not only the Stamp Act but also the Declaratory Act, which asserted Britain’s full right to tax the colonies.

In Parliament, Barré used his fiery oratory to defend colonial rights, repeatedly challenging the rationale behind Britain’s restrictive policies. He maintained that the American colonies were justified in their objections and that continued mistreatment could drive them to resist. Although his warnings went largely unheeded, Barré’s speeches in support of American rights left a powerful impression on both sides of the Atlantic.

Physical Appearance and Parliamentary Persona

Isaac Barré’s physical appearance played a role in his parliamentary persona. He was described by contemporary Horace Walpole as “a black, robust man, of a military figure” with “a peculiar distortion on one side of his face.”

The injury from the Battle of Quebec, where a bullet wound had damaged his cheek and left him partially blind in one eye, gave him a fierce, intimidating presence. This “savage glare” in one eye added to the effect of his passionate, vigorous speeches and helped him stand out as a commanding figure in Parliament.

Later Years, Health Decline, and Retirement

In 1783, Barré’s health began to deteriorate as he lost his sight entirely, forcing him to miss several sessions in Parliament. Though he later returned to his seat, his effectiveness had waned, and he retired in 1790 after nearly three decades of political service. Barré spent his remaining years in London, where he continued to live comfortably due to his accumulated wealth from his various government positions.

Isaac Barré passed away on July 20, 1802, at his home on Stanhope Street in London’s Mayfair district. He was buried in the St. Mary Churchyard in East Raynham. His primary beneficiary was Anne Townshend, Marchioness Townshend, whom he had known before her marriage to George Townshend, 1st Marquess Townshend. She inherited approximately £24,000 from his estate, a considerable sum for the time.

Legacy and Commemoration

Barré’s legacy endures primarily through his support for American colonial causes and his powerful speeches in Parliament. His coining of the term “Sons of Liberty” became iconic, symbolizing the colonists’ struggle for justice and independence. This term inspired a wide network of organizations in America that resisted British policies and eventually played a part in the revolutionary movement.

In honor of his contributions, several American towns and cities bear his name. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, a city named jointly for Barré and John Wilkes, reflects American appreciation for his advocacy. The town of Barre, Massachusetts, and both Barre City and Barre Town in Vermont were also named in his honor. Various streets across the eastern United States bear his name, a tribute to his lasting impact on American history.

Isaac Barré remains a unique figure in British and American history—a soldier who became a fierce defender of American colonial rights within the British Parliament. His military service and his skillful oratory contributed to his distinct role in the events leading up to the American Revolution. His passionate defense of liberty and his complex, sometimes controversial career make him a noteworthy historical figure, especially as someone who straddled two worlds: the British Empire and the American colonies whose liberties he staunchly defended.

Frequently Asked Questions

What were Isaac Barré’s early life and family background?

Isaac Barré was born on October 15, 1726, in Dublin to Huguenot refugees Marie Madelaine and Peter Barré, a linen dealer and High Sheriff of Dublin. He attended Trinity College, graduating in 1745.

What career path did Barré initially choose, and why?

Although his family encouraged him to pursue law, Barré chose a military career and joined the British Army’s 32nd Regiment of Foot in 1746, which eventually led him to notable achievements in both military and political arenas.

Where did Barré first gain military experience, and what were his early ranks?

He first served in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748) and later became a lieutenant and captain in the 32nd Regiment, building a reputation for bravery and competence.

How did Barré’s service during the French and Indian War enhance his reputation?

Serving under General James Wolfe, he fought in key battles at Louisbourg and Quebec, where he was severely wounded and lost vision in one eye. This injury gave him a fierce appearance and cemented his status as a decorated officer.

How did Lord Shelburne support Barré’s transition to politics?

After his military career, Shelburne helped Barré enter Parliament as the representative for Chipping Wycombe in 1761. Shelburne valued Barré’s speaking skills and introduced him to influential political circles.

What was Barré’s stance on Britain’s taxation of the American colonies?

Barré opposed British taxation of the American colonies. During debates on the 1765 Stamp Act, he famously defended colonial rights, describing American colonists as the “Sons of Liberty” and criticizing British policies that disregarded colonial grievances.

What government positions did Barré hold during his political career?

He served as Vice-Treasurer of Ireland (1766–1768), Treasurer of the Navy (1782), Paymaster General of the Forces (1782–1783), and Clerk of the Pells (1784). These positions provided him with both influence and substantial income.

How did Barré’s understanding of North American issues affect his political influence?

Barré’s relationships with American merchants and colonists deepened his knowledge of North American issues, making him a strong voice in Parliament against British taxation policies and an advocate for colonial grievances.

Image: A 1785 painting of Isaac Barré. Artwork by Gilbert Stuart.

What was notable about Barré’s physical appearance, and how did it impact his parliamentary presence?

Horace Walpole described him as “black, robust, of a military figure” with a “savage glare” due to a bullet wound in his cheek, which gave him an intimidating presence and added to his reputation as a fierce orator.

What marked the later years of Barré’s life and political career?

He became blind in 1783 and retired from Parliament in 1790. Barré died on July 20, 1802, in London, leaving a significant inheritance to Anne Townshend, Marchioness Townshend.

How is Barré’s legacy remembered today?

His legacy endures through his advocacy for American colonial rights, his military service, and places in the United States named in his honor, such as Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and several towns and streets across the eastern United States.