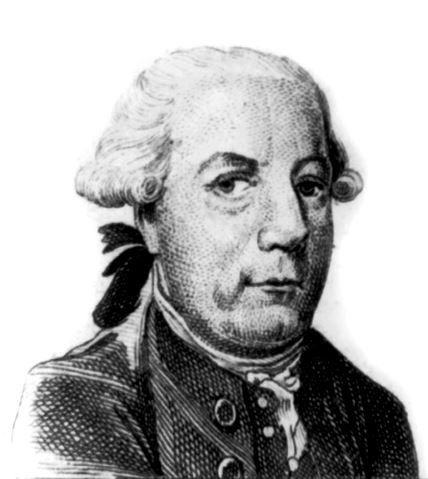

Founding Father Henry Laurens

Henry Laurens (1724–1792) was a significant figure in American history, remembered for his contributions to the American Revolution, his role in diplomatic missions, and his complex legacy as a wealthy merchant and slave trader. Born into a prosperous family with Huguenot heritage, Laurens’s life reflected both the opportunities and contradictions of colonial America. His career ranged from building wealth in the slave trade to championing the cause of independence, and his influence extended from the political halls of South Carolina to the international negotiations that helped secure American independence.

As a Founding Father, Henry Laurens succeeded John Hancock as president of the Second Continental Congress, overseeing the passage of the Articles of Confederation. Image: An engraving from 1784 depicts Laurens in his role as President of the Continental Congress.

Early Life and Family Background

Laurens was born on March 6, 1724, in Charleston, South Carolina, to John Laurens, a successful saddler, and Hester Grasset, both French Huguenots who had fled religious persecution in France. Laurens’s grandfather, Andre, immigrated from France in 1682 following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, which led to renewed religious persecution of Protestants. Andre first settled in New York City and later moved to Charleston, where the Laurens family became established among South Carolina’s rising merchant class.

Henry Laurens grew up in Charleston and was exposed early to commerce, especially through his father’s profitable saddlery business. In 1744, he traveled to London to complete his business education, where he was mentored by Richard Oswald, an influential merchant. Oswald’s tutelage introduced Laurens to the larger world of commerce, finance, and international trade, and he returned to Charleston with a solid understanding of business practices that would help him grow his wealth.

Building Wealth in Colonial America

When Laurens’s father died in 1747, Laurens inherited a considerable estate, which he used to expand his commercial ventures. He formed a partnership with George Austin in the Austin and Laurens Company, which became the largest slave-trading firm in North America. Through this business, Laurens profited greatly by importing and selling enslaved Africans. In the 1750s alone, Austin and Laurens oversaw the sale of more than 8,000 enslaved individuals, establishing Laurens as one of South Carolina’s wealthiest men.

In addition to his involvement in the slave trade, Laurens also invested in rice plantations, which were lucrative in the Carolina Lowcountry. These plantations relied heavily on enslaved labor, and by the time of his death, Laurens owned approximately 260 enslaved individuals. His investments in both the slave trade and agriculture allowed him to build a fortune, making him a prominent figure in South Carolina society. Despite his participation in the slave trade, Laurens later struggled with conflicting feelings about slavery, a moral tension highlighted by the abolitionist sentiments of his son, John Laurens.

Military and Political Career in South Carolina

Laurens’s prominence in South Carolina led him to public service. In 1750, he married Eleanor Ball, a member of a prominent rice-planting family, further solidifying his status within South Carolina’s elite. Together, they had thirteen children, though only three survived to adulthood. His wife’s death in 1770 left him responsible for raising his children, including his son John Laurens, whom he sent to England for education.

Laurens entered the political arena in the mid-1750s. During the French and Indian War, he joined the South Carolina militia, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel while participating in campaigns against the Cherokee. Laurens also began his career in colonial politics, winning election to South Carolina’s colonial assembly in 1757. Except for a brief hiatus in 1773, he held his seat until the Revolutionary War. Initially, Laurens supported reconciliation with Britain and even expressed loyalty to the British Crown, but as the revolutionary movement intensified, his allegiance shifted toward independence.

Revolutionary Leadership and the Continental Congress

With tensions between the colonies and Britain escalating, Laurens emerged as a revolutionary leader in South Carolina. In 1775, he was elected to the South Carolina Provincial Congress, where he served as president of the Committee of Safety. As the de facto government of South Carolina, the Committee of Safety played a crucial role in organizing resistance to British rule. Laurens’s leadership abilities made him an essential figure in South Carolina’s early revolutionary government, and he served as vice president of the state from 1776 to 1777, holding significant influence in the newly formed government.

In 1777, Laurens was selected as a delegate to the Continental Congress, where he quickly rose to prominence. In November of that year, he succeeded John Hancock as president of the Continental Congress, a role he held until December 1778. As president, Laurens played an instrumental role in the formal adoption of the Articles of Confederation, which established a foundational structure for the new United States government. During his tenure, Laurens navigated the challenging task of uniting various factions within the Congress and maintaining morale as the colonies fought for independence.

Laurens used his position to champion American independence, encouraging Congress to secure foreign aid and alliances, particularly from France. His efforts to keep the Continental Congress united during this turbulent period were significant, especially as the war with Britain took a heavy toll on the young nation. Under Laurens’s leadership, the Congress worked to support the Continental Army and negotiate alliances that would prove crucial to the American cause.

Image: John Hancock

Diplomatic Mission to the Netherlands and Capture by the British

In 1779, the Continental Congress appointed Laurens as the United States’ diplomatic envoy to the Netherlands, where he was tasked with securing Dutch financial support and military assistance for the American war effort. Laurens’s mission was part of a broader strategy to cultivate European alliances, which had become essential as the British sought to isolate the American colonies diplomatically.

In early 1780, Laurens embarked on his mission, but on his return voyage to Amsterdam later that year, the British frigate Vestal intercepted his ship. Laurens attempted to prevent British authorities from seizing sensitive diplomatic documents by ordering them tossed overboard, but British forces managed to retrieve a draft of a proposed treaty between the United States and the Dutch. This discovery led Britain to declare war on the Netherlands, initiating the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War.

The British charged Laurens with treason and imprisoned him in the Tower of London, where he remained for over a year. He was the only American to be held in the Tower during the Revolutionary War, and his imprisonment became a significant diplomatic issue. Richard Oswald, Laurens’s former business partner, advocated for his release, arguing his case before British officials. After lengthy negotiations, Laurens was eventually freed on December 31, 1781, in a prisoner exchange for British General Lord Cornwallis, who had been captured following the British defeat at Yorktown.

The Death of John Laurens and Role in the Treaty of Paris

In August 1782, Laurens’s son John, a passionate abolitionist and revolutionary soldier, was killed in the Battle of the Combahee River. John Laurens had been a vocal advocate for the enlistment of enslaved people in the Continental Army, with the promise of emancipation for those who served. He had urged his father to set an example by freeing his own enslaved workers, but Henry Laurens ultimately did not act on his son’s pleas.

Shortly after his son’s death, Laurens was named one of the peace commissioners sent to Paris to negotiate an end to the Revolutionary War. Richard Oswald, his former partner in the slave trade, represented Britain in these talks, while Laurens worked alongside John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and John Jay. Although Laurens was not a signatory of the primary Treaty of Paris in 1783, he contributed to secondary agreements involving the Netherlands and Spain, helping to secure the independence of the United States.

Later Years and Retirement

After the Treaty of Paris, Laurens largely retired from public life, choosing to live quietly at his Mepkin estate in South Carolina. The British occupation during the war had left his estate severely damaged, with his home burned by British forces. He spent much of his post-war life attempting to rebuild Mepkin, enduring significant financial losses from the Revolution, which he estimated at £40,000.

Although he was urged to rejoin public service by returning to the Continental Congress and participating in the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Laurens declined these invitations. He did, however, participate in the South Carolina convention of 1788, where he voted to ratify the U.S. Constitution, demonstrating his support for a stronger federal government. Laurens’s contributions to the founding of the United States were recognized by his fellow statesmen, but his role in the slave trade and his decision to continue holding enslaved people complicated his legacy.

Death and Legacy

Laurens suffered from gout in his later years, a painful condition that limited his mobility and contributed to his decline in health. He died on December 8, 1792, at his estate, Mepkin, in South Carolina. In his will, Laurens requested to be cremated, an unusual choice in colonial America, driven by his fear of being buried alive. He was reportedly the first white American to be cremated, and his ashes were interred at Mepkin.

Laurens’s legacy is complex, reflecting both his critical contributions to the Revolution and the contradictions of his wealth, which was largely built on the labor of enslaved Africans. His son John had been a passionate advocate for the abolition of slavery, yet Laurens himself retained ownership of approximately 260 enslaved people, despite his expressed internal conflict about the institution.

In recognition of Laurens’s role in the founding of the United States, several places were named after him. Laurens County in South Carolina, as well as the towns of Laurens in South Carolina and New York, honor his influence. Laurens County, Georgia, is named after his son John, highlighting the family’s contributions to American independence. Laurens’s friend and colleague General Lachlan McIntosh named Fort Laurens in Ohio in his honor, further commemorating his legacy.

Mepkin Abbey and Historical Legacy

Laurens’s Mepkin estate has endured as a part of his legacy. In 1949, the estate was donated to the Roman Catholic Church and became Mepkin Abbey, a Trappist monastery and spiritual retreat. Today, Mepkin Abbey serves as both a historical landmark and a place of contemplation, preserving the memory of Laurens’s life and his contributions to American history. The abbey also offers visitors an opportunity to reflect on the complexities of America’s revolutionary generation, whose lives and legacies often included paradoxes of both principle and practice.

The story of Henry Laurens encapsulates the dualities of the American founding. As a Founding Father, Laurens was committed to the cause of liberty and independence, yet his wealth was tied to the institution of slavery. His role in the American Revolution and subsequent peace negotiations was instrumental, and his contributions to the new nation’s government were significant. However, his life also serves as a reminder of the moral complexities faced by some of the United States’ early leaders, who, while fighting for freedom, benefited from the unfreedom of others.

Frequently Asked Questions

What were Henry Laurens’s origins and family background?

Henry Laurens was born on March 6, 1724, to John Laurens and Hester Grasset, both Huguenots who fled France for religious freedom. His grandfather, Andre Laurens, settled in Charleston, South Carolina, where the family established a successful saddlery business.

How did Laurens build his wealth before the Revolutionary War?

Laurens inherited his father’s estate and expanded into a partnership with the Austin and Laurens Company, North America’s largest slave-trading firm. Through slave trading and rice plantations, Laurens amassed significant wealth and became one of South Carolina’s wealthiest individuals.

Who was Eleanor Ball, and how did her marriage to Laurens impact him?

Eleanor Ball was the daughter of a prominent South Carolina rice planter. Laurens married her in 1750, further integrating into the elite planter class. Together, they had thirteen children, though many did not survive childhood.

How did Laurens become involved in military and political life?

During the French and Indian War, Laurens served in the South Carolina militia, rising to lieutenant colonel. He also entered political life, being elected to South Carolina’s colonial assembly in 1757, where he served regularly until the American Revolution.

Image: Portrait by English painter Lemuel Francis Abbott.

What was Laurens’s role in the Continental Congress?

Laurens served as president of the Continental Congress from November 1777 to December 1778, succeeding John Hancock. He oversaw the signing of the Articles of Confederation, helping to shape the United States’ first national government.

What was Laurens’s mission to the Netherlands, and why was it significant?

In 1779, Laurens was appointed U.S. minister to the Netherlands to secure Dutch support for the Revolution. However, he was captured by the British on his return journey. His capture led to Britain’s declaration of war on the Dutch, escalating the conflict.

What happened during Laurens’s imprisonment?

The British imprisoned Laurens in the Tower of London, the only American held there during the war. His release was negotiated in a prisoner exchange for British General Cornwallis, which allowed Laurens to return to the Netherlands to help raise American funds.

How did the death of John Laurens influence Henry Laurens’s views on slavery?

John Laurens, Henry’s son, advocated for freeing enslaved people and encouraged his father to begin with the family’s enslaved workers. Although Henry Laurens was conflicted, he ultimately did not free his enslaved people, reflecting his internal struggle over the issue.

What role did Laurens play in the Treaty of Paris?

Laurens served as a peace commissioner in the Paris negotiations of 1783, contributing to the treaty that ended the Revolutionary War. His former partner, Richard Oswald, represented Britain, and Laurens focused on secondary agreements with Spain and the Netherlands.

What was Mepkin Abbey, and how is it connected to Laurens?

Laurens’s Mepkin estate, where he spent his later years, was donated in 1949 to the Roman Catholic Church and became Mepkin Abbey, a Trappist monastery. The estate remains a preserved historical site and a testament to Laurens’s life and legacy.