King Thoas in Greek Mythology

King Thoas is a complex figure in Greek mythology, appearing in multiple myths and taking on different roles depending on the narrative and sources. He is best known as a ruler associated with both the Taurians and Lemnos, and his story involves themes of familial loyalty, divine intervention, and heroism. His character serves as a connection point in myths that explore the interaction between gods, heroes, and mortals, notably within the tragic context of Iphigenia, Orestes, and the tales surrounding his daughter, Hypsipyle.

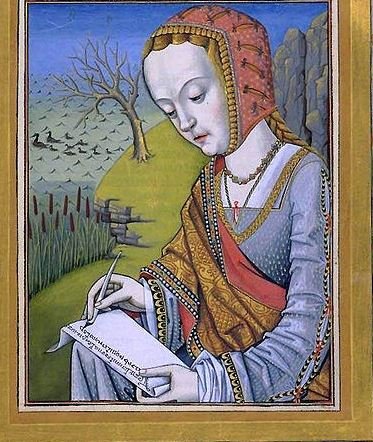

Image: Thoas being saved by his daughter Hypsipyle.

Thoas as King of the Taurians

In Euripides’ play Iphigenia among the Taurians, Thoas is the king of the Taurians, a tribe located on the northern shores of the Black Sea, in what is now Crimea. The Taurians were seen as a barbaric, remote people by the Greeks, adding an exotic element to the myth. In the play, Thoas rules over a land where Iphigenia, the daughter of Agamemnon, serves as a priestess of Artemis. Iphigenia was brought to this distant land by the goddess Artemis, who saved her from being sacrificed by her father in Aulis.

Thoas is portrayed as a strict and obedient ruler who dutifully enforces the rituals demanded by his people’s interpretation of Artemis’s worship. One of his key responsibilities is to ensure that any foreigners landing on Taurian shores are captured and sacrificed to Artemis. This duty brings him into direct conflict with Iphigenia’s brother, Orestes, who arrives in Tauris with his friend Pylades to retrieve a sacred statue of Artemis as part of his quest for purification after the murder of his mother, Clytemnestra.

When Orestes and Pylades are captured, they are brought to Iphigenia, who, unaware of their identities, prepares to perform the ritual sacrifice as ordered by Thoas. Upon recognizing her brother, however, she devises a plan to escape rather than submit to the sacrificial custom enforced by Thoas. While Orestes considers killing Thoas to facilitate their escape, Iphigenia instead decides to deceive him by claiming that Orestes, as a matricide, is polluted and must be ritually cleansed in the sea. Thoas, believing her, grants permission, unknowingly allowing them to escape with both the statue and Iphigenia.

Thoas’s reaction to their escape is swift and shows his authoritative nature; upon learning of the deception, he orders his men to pursue them. However, divine intervention occurs in the form of Athena, who appears to Thoas and commands him to abandon the chase and allow Orestes and Iphigenia their freedom. This ending reflects the tension in Greek mythology between human actions and divine will. Thoas, as an earthly authority, submits to the gods, reinforcing the idea that mortals must ultimately bow to divine power and destiny.

Thoas as King of Lemnos and Father of Hypsipyle

In another mythological tradition, Thoas is known as the king of the island of Lemnos, where he is also famously the father of Hypsipyle. This version of Thoas appears in the Argonautica by Apollonius of Rhodes and in various other ancient sources. On Lemnos, Thoas’s story takes a dramatic turn with the “Lemnian crime,” a gruesome episode involving the massacre of the island’s male population by the women of Lemnos.

According to this story, the women of Lemnos, angry that their husbands had taken Thracian concubines during a supposed divine punishment that made the women smell foul, revolted and murdered all the men on the island, including their husbands and fathers. Hypsipyle, however, could not bring herself to kill her father, Thoas. Instead, she hid him and eventually set him adrift on the sea in a hollow chest, allowing him to escape the massacre. Thoas’s survival is attributed to the compassion of his daughter, who, despite the women’s collective decision, defies them out of filial loyalty.

There are various accounts of what happens to Thoas after his escape. In Apollonius’s Argonautica, he is rescued by fishermen who take him to the island of Sicinus, where he finds refuge. Other versions of the myth provide different outcomes; in some accounts, he lives quietly in exile, while in others, he eventually returns to his kingdom. In Hyginus’s version, Thoas, the Lemnian king, is identified with the Taurian Thoas, creating a continuity in which he crosses paths with Iphigenia and Orestes in later stories, though this identification is not universally accepted in all ancient sources.

Thoas’s Characteristics and Symbolism

Thoas embodies several qualities typical of a mythological king: authority, a duty to uphold religious customs, and a sense of obligation to his people and his family. As the ruler of the Taurians, Thoas represents the foreign, non-Greek world, perceived by the Greeks as harsh and uncivilized, yet still bound by its own rules and divine observances. His character reflects a rigid adherence to tradition, which he is willing to defend even when faced with challenges posed by foreign captives and the personal pleas of his priestess, Iphigenia.

In his role as the Lemnian king, Thoas is portrayed as a more sympathetic figure, especially in the story of his escape orchestrated by his daughter. This version of Thoas emphasizes themes of family loyalty and the power of compassion over collective vengeance. Hypsipyle’s choice to save him from the massacre highlights the personal loyalty that can transcend even the most entrenched cultural norms.

The contrast between Thoas’s Taurian and Lemnian portrayals may also reflect broader Greek views on foreignness and civilization. As a Taurian king, he enforces a brutal custom, underscoring the perceived barbarism of distant lands. Yet as a Lemnian king, he is portrayed as a victim of cruelty from his own people, and his survival adds a layer of complexity to his character. In both roles, however, he remains a figure influenced by the wills of others—whether the women of Lemnos, his daughter, or the goddess Athena.

Divine Intervention and the Will of the Gods

In both the Taurian and Lemnian stories, Thoas is ultimately subject to forces beyond his control. In Iphigenia among the Taurians, his willingness to relent in the face of Athena’s command underscores the limitations of human authority in Greek mythology. Despite his desire to pursue Orestes and Iphigenia, Thoas submits to Athena’s divine authority, demonstrating the common mythological theme that mortals, regardless of their status or power, must yield to the gods.

In the story of the Lemnian crime, Thoas’s survival is a result of his daughter’s intervention, which can be interpreted as another form of “divine” rescue, in that familial love and loyalty take precedence over communal vengeance. Though not a divine intervention in the traditional sense, Hypsipyle’s act of saving her father reflects an internal, moral compass that aligns with the ideals of piety and respect for family.

This interplay between human choices and divine or moral intervention gives Thoas’s character a certain depth, as he exists in a space where his actions are heavily influenced by the decisions of others. His character serves as a reminder of the Greek worldview in which human lives are intertwined with fate, divine will, and the unpredictable actions of others.

Did you know…?

According to the Greek grammarian Antoninus Liberalis, the poet Nicander claimed Thoas was the son of the river god Borysthenes, associated with the Dnieper River north of Greece.

Thoas’s Legacy and Influence

King Thoas’s presence in multiple myths and his connections to significant figures like Iphigenia, Orestes, and Hypsipyle make him a recurring figure whose actions resonate across different mythological traditions. In some accounts, his role as king intersects with foundational mythological events, such as the formation of Greek religious practices (the Taurian sacrifices) and the adventures of the Argonauts (his daughter Hypsipyle’s encounter with Jason).

Thoas’s story also serves as a narrative bridge between different mythological episodes, especially through Hyginus’s merging of the Taurian and Lemnian kings into a single figure. By blending these stories, ancient authors like Hyginus highlight the thematic continuity in Greek mythology, where seemingly disparate narratives are connected by shared motifs of loyalty, divine intervention, and cultural values.

Moreover, Thoas’s character reflects the fluid nature of mythological figures in Greek tradition, as they often serve multiple roles and embody different values depending on the context. Thoas’s representation as both a strict enforcer of sacrificial customs and a sympathetic father figure allows audiences to explore various facets of ancient Greek society, from its rigid observance of religious rites to its emphasis on family bonds.

Conclusion

King Thoas occupies a unique position in Greek mythology as both a ruler who enforces harsh customs and a victim of tragic familial circumstances. His dual portrayal as the Taurian king who pursues Orestes and Iphigenia and the Lemnian king spared by his daughter Hypsipyle offers a rich exploration of themes central to Greek myth: the tension between human law and divine will, the power of compassion within family dynamics, and the often complex portrayal of foreignness and “barbarism.”

In Iphigenia among the Taurians, Thoas represents the rigid adherence to local customs that often clashes with the desires of individuals, while also highlighting the limitations of human power in the face of divine intervention. The intervention of Athena in Euripides’ play serves as a reminder of the omnipresence of the gods in human affairs and the ultimate authority they hold over mortal lives.

In contrast, Thoas’s story on Lemnos offers a more sympathetic view, where the king’s survival depends on familial love rather than divine intervention. Hypsipyle’s choice to save him not only spares his life but also adds a layer of human compassion that contrasts sharply with the brutal collective actions of the Lemnian women. Through his character, Greek mythology explores both the adherence to and deviation from cultural and familial obligations.

Overall, King Thoas’s mythology demonstrates the complexity of Greek storytelling, where characters are often caught between conflicting forces of duty, love, and divine will. His story, encompassing both adherence to ritual and the bonds of family, reflects the nuanced portrayal of human experiences within Greek myth, illustrating the themes that have made these ancient stories endure through the centuries.

Image: Hypsipyle

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the central conflict in Iphigenia among the Taurians?

The central conflict is that Iphigenia, forced by King Thoas to sacrifice any Greek foreigners to Artemis, must decide what to do when her brother Orestes is brought to her as a sacrificial captive.

How does Iphigenia recognize Orestes?

During the preparations for sacrifice, the siblings realize each other’s identities, leading them to devise an escape plan.

What plan does Orestes suggest to escape?

Orestes initially suggests killing Thoas as a means of escape.

How does Iphigenia’s escape plan differ from Orestes’ suggestion?

Instead of using violence, Iphigenia plans to deceive Thoas by telling him that Orestes needs to be purified in the sea due to his crime of matricide, allowing her to take him and the sacred statue to the shore for an escape.

How does King Thoas respond to Iphigenia’s request?

King Thoas believes Iphigenia’s explanation and permits her to take Orestes to the sea for the ritual, inadvertently giving them the chance to escape.

What happens when Thoas learns of their escape?

A messenger informs Thoas of the siblings’ escape, and he orders his men to pursue them.

Who intervenes to prevent Thoas from capturing Orestes and Iphigenia, and what is the result?

The goddess Athena intervenes, convincing Thoas to abandon his pursuit and allowing Orestes and Iphigenia to escape safely.

How does Hyginus’ version of the story differ from Euripides’?

In Hyginus’ version, Thoas pursues the siblings to the island of Chryse, where they encounter Chryses, their half-brother, who kills Thoas, ensuring their safety.