Netotiliztli

Netotiliztli was a traditional dance practiced by the Mexica people, a Nahuatl-speaking civilization that flourished in central Mexico before the Spanish conquest. This dance was deeply intertwined with Mexica cosmology, religion, and social structure.

The Mexica resided in Tenochtitlan, their powerful capital city, located on an island in Lake Texcoco. With a population estimated to be close to quarter of a million, Tenochtitlan functioned as the heart of Mexica political, social, and religious life.

Mexica society was structured around an altepetl, or city-state, which was divided into smaller units called calpulli. These functioned as neighborhoods and centers of economic and social organization. At the core of Tenochtitlan was the sacred precinct, which housed the Great Temple, a ball court, schools, libraries, and residences for priests. It was within these sacred spaces that rituals, sacrifices, and dances such as Netotiliztli were performed, making dance an integral part of Mexica spiritual and communal life.

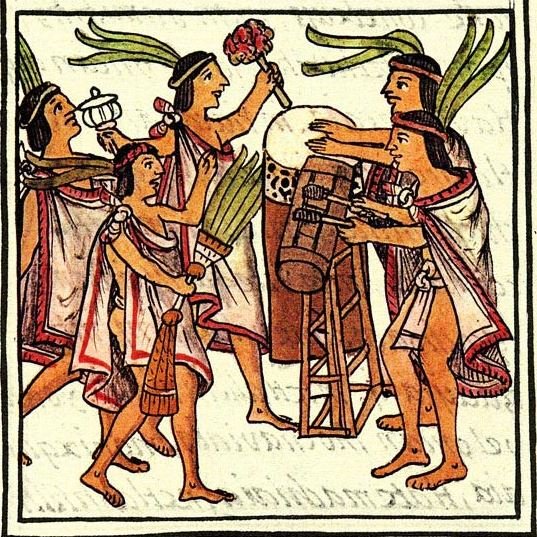

A depiction of a traditional dance ritual from the Florentine Codex, a 16th-century manuscript. In the background, musicians play teponatzli, while huehuetls can be seen further back.

Netotiliztli is a traditional Mexica dance of celebration and worship, symbolizing spiritual connection to the gods.

Social and Spiritual Significance

Mexica society was hierarchical, with the Tlatoani (emperor) at the top, followed by noble classes, warriors, commoners, and slaves. While men dominated politics, warfare, and priesthood roles, women played crucial roles in domestic life. However, one cultural aspect that united all members of society, regardless of gender or status, was the practice of music and dance. Boys were trained in governance, warfare, and religious rites, while girls were educated in domestic arts. Yet, both genders learned the fundamentals of music and dance, emphasizing their cultural and spiritual importance.

At the core of Mexica religion was the belief in a reciprocal relationship between gods and humans. According to their mythology, the gods sacrificed themselves to create the world, including the sun and humankind. In return, the Mexica performed rituals, including bloodletting and human sacrifices, to sustain the gods. Netotiliztli was a non-violent extension of this tradition—a dance dedicated to expressing gratitude, worship, and seeking divine favor.

Symbolism and Performance of Netotiliztli

The word Netotiliztli translates to “expressed by dance,” highlighting its communicative nature. It was performed by individuals from all social strata, reinforcing the idea that dance was a shared cultural practice rather than a privilege of the elite. Netotiliztli did not have a fixed location for performance; it could be practiced in temples, public spaces, or private gatherings. Often, these dances were held in alignment with agricultural cycles, serving as celebrations that marked the beginning of the planting season, seeking divine blessings for a bountiful harvest.

The dance was deeply symbolic, with movements representing natural elements—earth, water, fire, and wind—as well as the four cardinal directions. Participants formed circular patterns around a central fire pit, symbolizing the cosmos and the sun, which was regarded as the lifeblood of existence. At the center of the dance were large drums that mimicked the heartbeat of the universe. Dancers often imitated the movements of animals, clouds, or celestial bodies, embodying natural forces in their ritual expressions. Women, in particular, played a special role as sahumadoras or “smoke women,” burning incense to cleanse the space and facilitate communication with the gods.

Regalia and Musical Accompaniment

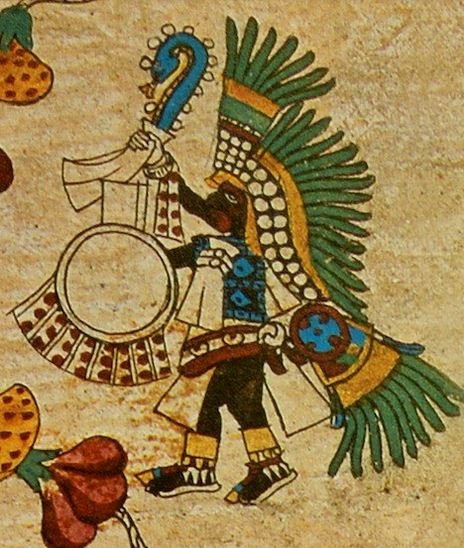

Dancers adorned themselves with intricate regalia that incorporated feathers, jewelry, and patterned fabrics. These elements were not merely decorative; they carried spiritual significance.

For example, the feathered headdresses represented Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent deity associated with wisdom, life, and agriculture. Snakes, seen as symbols of fertility and rebirth due to their shedding skin, also influenced the dance’s aesthetic and movements. The color red was commonly worn, signifying protection, joy, and purification.

Dancers wrapped red sashes around their heads and waists, believing they would shield them from negative energy during the performance.

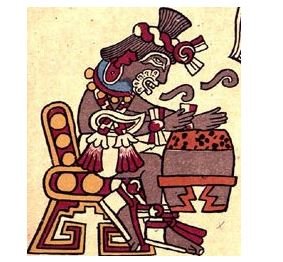

Music played a vital role in Netotiliztli. According to Cantares Mexicanos, a collection of indigenous songs and dance traditions, the performance was accompanied by powerful rhythmic beats and melodic chants. Traditional instruments included huehuetls (large wooden drums), teponaztli (log drums), flutes, and rattles such as ayoyotes (seed pod anklets). These instruments mimicked natural sounds like rainfall, wind, and bird calls, creating an immersive auditory experience that connected the dancers to the elements.

Some accounts suggest that Netotiliztli functioned as a form of spiritual invocation. Through rhythmic motion and chant, dancers were believed to channel ancestral spirits and divine energies. This belief extended beyond the Mexica, influencing indigenous and Mestizo communities that preserved elements of the dance in later traditions.

READ ALSO: Food & Agriculture in the Aztec Empire

Impact of the Spanish Conquest on Netotiliztli

The Spanish conquest of Mexico in the early 16th century had a profound impact on indigenous religious and cultural practices, including Netotiliztli. The Spanish viewed Mexica dances, particularly those tied to religious ceremonies, as pagan rituals that conflicted with Christianity. Consequently, many indigenous traditions were suppressed, and their practitioners were persecuted.

However, Netotiliztli survived through adaptation. To continue practicing their ancestral traditions, the Nahua people transformed the dance from a religious ritual into a more secularized form of artistic expression. Over time, elements of Christian practices were woven into indigenous celebrations, allowing dances to persist under the guise of festivity rather than religious worship. This syncretism enabled Netotiliztli to be practiced without direct confrontation from colonial authorities.

Netotiliztli in Contemporary Mexico

An illustration from Codex Borbonicus depicting an Aztec dancer.

Today, Netotiliztli is no longer performed in its original pre-Hispanic context. However, its legacy endures through various indigenous and folkloric dances that retain similar movements, symbolism, and cultural significance. Traditional Aztec dances, such as the Danza de los Concheros, Voladores, and Deer Dance, continue to be performed at festivals and ceremonies across Mexico, preserving elements of Mexica choreography and spirituality.

While Spanish colonization altered its practice, elements of Netotiliztli persist in modern Mexican dance traditions.

These dances serve as a form of cultural identity and resistance for indigenous communities, reconnecting modern practitioners with their ancestral heritage.

Additionally, Mexican folkloric ballet incorporates pre-Columbian dance influences, integrating indigenous styles into national artistic expressions.

While the spiritual essence of Netotiliztli may have evolved over centuries, its core themes of celebration, reverence, and connection to nature remain embedded in Mexican dance traditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What elements and directions are represented in Netotiliztli?

The dance movements correspond to the four elements (water, fire, wind, and earth) and the four cardinal points.

Who participated in Netotiliztli?

All members of Mexica society, regardless of status or gender, were educated in dance and could participate.

What was the significance of dance in Mexica society?

Dance was a fundamental part of education, religion, and festivals, reinforcing cosmic balance and devotion to the gods.

How did Netotiliztli reflect Mexica cosmology?

Dancers imitated celestial movements, animals, and natural elements to honor deities and ensure prosperity.

What role did women play in Netotiliztli?

Women could participate as dancers or serve as sahumadoras (smoke women), burning incense to enhance spiritual energy.

What kind of music and instruments accompanied Netotiliztli?

Drums (huēhuētls, teponaztli), flutes, and seed pod rattles (ayoyotes) were used to create rhythmic, nature-inspired sounds.

A drawing depicting an Aztec drummer playing the Huehuetl.

How did dancers dress for Netotiliztli?

They wore feathered headdresses, red sashes, patterned capes, and jewelry, often symbolizing deities like Quetzalcoatl.

How did Netotiliztli survive Spanish colonization?

It was adapted to remove explicit religious significance and incorporated elements of Christian rituals.

Is Netotiliztli still practiced today?

While Netotiliztli itself is no longer a central tradition, elements of Mexica dance survive in festivals and cultural performances in Mexico.

FACT CHECK: At World History Edu, we strive for utmost accuracy and objectivity. But if you come across something that doesn’t look right, don’t hesitate to leave a comment below.