Origin Story of Byzantine Monasticism

Byzantine monasticism stands as one of the defining pillars of the Eastern Roman Empire’s religious, social, and cultural life. Unlike Western monasticism, which developed independently under the Benedictine Rule, Byzantine monasticism evolved from earlier Eastern Christian traditions rooted in desert asceticism. It combined mysticism, ascetic rigor, liturgical devotion, and an emphasis on contemplative isolation to shape a distinctive way of life that left an enduring imprint on Orthodox Christianity and beyond.

From humble cells in Egyptian deserts to the grandeur of Mount Athos, Byzantine monks not only shaped the spiritual outlook of the empire but also served as theologians, artists, missionaries, and often, reluctant political actors. Their monasteries were islands of spiritual retreat, yet they frequently became power centers in the Byzantine world.

Mor Gabriel Monastery in Southern Turkey.

READ ALSO: Western Historians’ Somewhat Biased Labeling of the Eastern Roman Empire

Origins in the Desert: The Eastern Roots

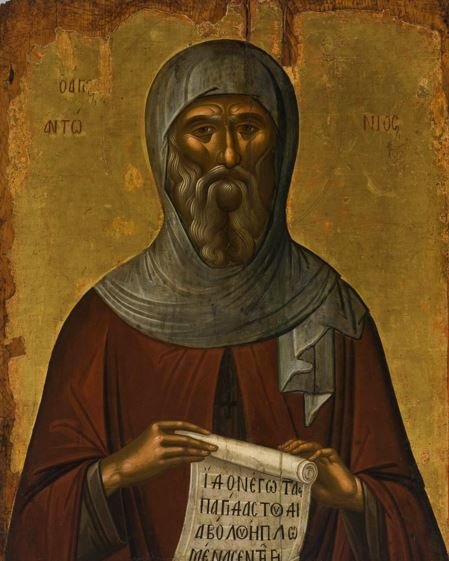

The foundations of Byzantine monasticism lie deep in the deserts of Egypt, Syria, and Palestine. The early Christian hermits of the 3rd and 4th centuries, particularly figures like Anthony the Great and Pachomius, carved out a new spiritual path—withdrawal from society for the sake of communion with God.

Anthony, considered the father of monasticism, embraced an eremitic lifestyle, retreating into the desert to live in solitude, prayer, and self-denial. His fame spread, and many followed his example.

On the other hand, Pachomius introduced the cenobitic model, where monks lived in a communal setting under a common rule and superior.

This dual legacy—eremitic and cenobitic—would become foundational for Byzantine monastic life. The ideal of the solitary hermit in direct contact with the divine would exist side by side with organized communities devoted to liturgical life and communal work. Early centers like Scetis in Egypt and the monasteries of Palestine became crucibles for the evolving spiritual ethos that would be carried into Byzantium.

A 16th century painting of Anthony the Great. Artwork by Michael Damaskinos.

Byzantine monasticism was far more than a religious vocation; it was a civilization within a civilization.

The Constantinian Shift and Institutionalization

With Constantine’s conversion and the imperial endorsement of Christianity in the 4th century, monasticism gained both visibility and complexity. Although monks remained on the margins of society in theory, the imperial church increasingly saw them as reservoirs of spiritual power and moral authority. They were seen as spiritual athletes, paragons of Christian discipline and detachment. Theodosius I’s establishment of Nicene Christianity as the state religion in the late 4th century further elevated their status.

As bishops and church councils began to formalize Christian doctrines, monks contributed significantly to the theological debates of the time. They supported orthodoxy during major controversies like Arianism and Nestorianism. Some even became bishops, although this was often against their will. Monks were admired not for their learning but for their ascetic authority and spiritual purity. Their perceived holiness gave their words weight, and their lives became models for the Christian faithful.

READ MORE: What was the Nicene Creed?

Constantinople and the Urban Monasticism

While the roots of monasticism lay in the wilderness, the Byzantine Empire brought it into the cities. Constantinople, the imperial capital, witnessed the rise of urban monasteries by the 5th century. These establishments provided spiritual services to the city’s inhabitants and sometimes functioned as charitable institutions, offering food, shelter, and medical care. Urban monasticism didn’t diminish the ascetic character of monastic life—it merely adapted it to the rhythms of imperial life.

Byzantine emperors, empresses, and aristocrats frequently endowed monasteries. These foundations were not merely acts of piety but also tools of influence. Founding a monastery could serve to immortalize one’s name, secure prayers for one’s soul, or create a political base. The connection between imperial patronage and monastic endowment meant that some monasteries acquired vast wealth and land, enabling them to operate semi-autonomously. This dynamic created a tension between monastic ideals and worldly involvement.

The Rise of Monastic Rules and Spiritual Traditions

In the early centuries, monastic life was not governed by a single, uniform rule as it would later be in the West. Instead, it was shaped by a variety of guidelines and spiritual texts, many of which originated with influential monks.

Basil the Great, bishop of Caesarea in the 4th century, wrote what would become the most important rule for Eastern monasticism. His “Asketikon,” a series of responses to questions posed by monks, emphasized communal life, obedience, humility, prayer, and work. Basil’s rule was flexible, adaptable, and deeply rooted in Scripture and the life of Christ.

Unlike the Rule of Saint Benedict, which became mandatory in Western Europe, Basil’s rule was never imposed universally in the East. It served more as a spiritual guideline than a codified legal structure. This allowed for a wide diversity of monastic practices across the Byzantine world. Nevertheless, Basil’s emphasis on community and service deeply influenced monastic development.

Other figures, such as John Cassian and Evagrius Ponticus, contributed to the spirituality and inner psychology of monasticism. Evagrius’s teachings on the eight logismoi, or evil thoughts, would eventually inform the Western idea of the seven deadly sins. These thinkers encouraged monks to strive for apatheia—freedom from passion—as a means to achieve union with God. Their writings created a shared spiritual vocabulary across the Eastern Mediterranean.

Liturgy, Prayer, and the Monastic Day

Byzantine monasticism was saturated with liturgical life. The daily routine of a monk revolved around the Divine Office, a series of prayers and psalms chanted at fixed hours. The centerpiece of this liturgical rhythm was the midnight office, which symbolized vigilance and readiness for the return of Christ. Vigils, matins, lauds, and vespers filled the day with structured prayer, recitation, and chant. The Psalms were especially central; monks typically memorized the entire Psalter.

The Jesus Prayer—“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner”—became a focal point of personal devotion. Repeated continually, this prayer was intended to cultivate inner stillness (hesychia) and focus the mind entirely on God. Over time, this prayer practice became systematized in the Hesychast tradition, which would dominate later Byzantine spirituality.

Monks also practiced fasting, silence, and manual labor as part of their spiritual regimen. Fasting was severe, particularly during Lent, and silence was seen as a way to guard against sin. Work included copying manuscripts, farming, and crafting liturgical items, depending on the monastery’s resources.

Monasteries as Economic and Cultural Hubs

Although ascetic withdrawal was the goal, monasteries often became centers of immense wealth and influence. Aristocrats frequently donated land, money, and relics to monasteries as acts of piety. Over centuries, some monasteries accumulated vast estates and became significant landowners. This wealth enabled them to fund charitable works, patronize artists and architects, and offer sanctuary during times of political or military crisis.

Monasteries were also key centers of learning and artistic production. Monks copied manuscripts, preserved classical Greek literature, and composed theological and philosophical works. Illuminated manuscripts, intricate mosaics, and frescoes adorned many monastic churches. The scriptoriums of monasteries such as Studios in Constantinople became renowned across the empire.

Moreover, monasteries offered practical services to the laity: lodging for pilgrims, education for boys, and basic healthcare. They were integral to the social fabric of Byzantium, especially in remote or rural areas where state infrastructure was limited.

Women in Byzantine Monasticism

Female monasticism flourished alongside male monasticism. Women, too, sought the ascetic life and created vibrant spiritual communities. Convents were often founded by imperial women or aristocratic widows, and they followed many of the same spiritual disciplines as male monasteries. Though more secluded, these communities offered women opportunities for education, leadership, and spiritual authority that were otherwise restricted in Byzantine society.

Prominent nuns such as Saint Olympias and Saint Theodosia were renowned for their piety and charitable work. Some convents became highly influential, with abbesses commanding respect from patriarchs and emperors alike. While women could not become priests or bishops, their roles as spiritual mothers and guides were deeply respected within Orthodox tradition.

The Mount Athos Phenomenon

Among all the monastic centers of Byzantium, Mount Athos stands out as the most enduring and iconic. Located on a remote peninsula in northern Greece, Athos became a monastic republic in the 10th century and remains so to this day. Its history is a living chronicle of Byzantine spiritual tradition.

Athos began as a place for hermits and gradually evolved into a network of monastic communities. In 963, the foundation of the Great Lavra by Saint Athanasius the Athonite marked the beginning of organized monasticism on the mountain. Over the next few centuries, Athos attracted monks from all over the Orthodox world—Greek, Slavic, Georgian, and more.

Mount Athos became a center for Hesychasm, a mystical tradition of contemplative prayer that emphasized the Jesus Prayer, bodily stillness, and inner illumination. By the 14th century, Hesychasm would become a defining feature of Athonite spirituality, particularly under the influence of figures like Gregory Palamas, who defended Hesychast practice against philosophical critics.

Athos was also granted privileges by successive Byzantine emperors, including exemption from taxation and imperial interference. It evolved into an autonomous spiritual polity, governed by an assembly of abbots. Despite its isolation, it remained deeply connected to the spiritual and political currents of the Orthodox world.

Mount Athos in 2005.

Hesychasm and the Palamite Controversy

In the 14th century, Byzantine monasticism became the site of a major theological controversy over the nature of mystical experience. The dispute arose when Barlaam of Calabria, a learned monk influenced by Western scholasticism, criticized the Hesychast practice of silent prayer and divine illumination. He argued that such experiences were subjective illusions, not genuine encounters with God.

Gregory Palamas, a monk of Mount Athos and later Archbishop of Thessalonica, defended Hesychasm. He distinguished between the essence and energies of God, asserting that while God’s essence remains unknowable, His energies can be experienced through prayer. This allowed the monk to encounter the uncreated light of God, as seen in the Transfiguration of Christ.

The Palamite theology was eventually endorsed by a series of synods in Constantinople (1341–1351), solidifying Hesychasm as orthodox doctrine in the Eastern Church. This victory not only affirmed the spiritual authority of the monks but also underscored the experiential, mystical dimension of Byzantine theology.

Decline and Endurance

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 marked the end of the Byzantine Empire but not of its monastic tradition. Monasteries adapted to life under Ottoman rule, often serving as preservers of Greek culture and Orthodox identity. They continued to produce saints, scholars, and spiritual guides well into the modern era.

Despite centuries of political upheaval, Mount Athos and other monasteries endured. They weathered iconoclasm, Latin crusades, and Islamic conquest. Their survival speaks to the resilience of the Byzantine monastic ideal—a life rooted not in power or prestige, but in spiritual discipline, communal worship, and the pursuit of divine union.

Legacy and Influence

Byzantine monasticism has had a profound and lasting influence on Eastern Christianity. Its spiritual practices, theological emphases, and liturgical traditions remain central to Orthodox monasticism today. The icons, chants, and architecture that emerged from Byzantine monasteries continue to inspire Orthodox believers across the globe.

Moreover, the Byzantine model influenced Slavic lands profoundly. Monks from Byzantium traveled to Bulgaria, Serbia, and Kievan Rus’, bringing with them liturgical texts, monastic rules, and artistic techniques. The great monasteries of Russia and the Balkans are direct heirs of the Byzantine tradition.

Even in the West, aspects of Byzantine monastic spirituality found echoes, especially in the mysticism of the medieval period. The commitment to a life of prayer, asceticism, and contemplation speaks to universal Christian ideals, transcending cultural and geographic boundaries.

Questions and answers about the Byzantine Monasticism

What was the role of monasticism in the Byzantine Empire?

Monasticism was a constant presence in Byzantine life, with individuals withdrawing from the world to pursue spiritual devotion. Monasteries became central to society by offering aid to the poor, shelter to travelers, refuge to disgraced nobles, and guidance to the faithful. They also played significant roles in land ownership, politics, and cultural preservation.

What inspired the development of Byzantine monasticism?

It was rooted in early Christian asceticism, influenced by Jewish traditions and figures such as Jesus and John the Baptist. Hermits in the Egyptian desert during the 3rd century CE, like Saint Anthony and Saint Mary of Egypt, exemplified the ideal of self-denial and divine closeness, laying the groundwork for communal monasticism.

An aerial view of Saint Catherine’s Monastery in 2010

How did monastic life transition from hermitage to communal living?

By the 4th and 5th centuries CE, monastic life evolved from solitary hermits to communal arrangements. Pachomios of Egypt introduced cenobitic monasteries, where monks lived together under a rule and an abbot’s guidance, sharing prayer, labor, and resources. Lavra communities also formed, balancing solitude with communal worship.

What was the nature of monasteries in Constantinople?

The first monastery in Constantinople, the Dalmatos, was founded in the late 4th century CE. By the 6th century, the city had around 30 monasteries. Byzantine monasteries operated independently, unlike the centralized orders of the Western Church. They were self-sufficient complexes often containing churches, refectories, baths, stables, and guest facilities.

Why were remote and mountainous regions favored for monastic sites?

Monks sought solitude and spiritual elevation in remote, mountainous areas believed to foster divine connection. These sites also attracted pilgrims looking for healing or spiritual experience. Major centers included Mount Sinai, Mount Olympos, and Mount Athos, the latter becoming a multinational monastic community and remaining active today.

How did monasteries accumulate wealth and sustain themselves?

From the 10th century CE, monasteries prospered through land donations, state privileges, and agricultural production. They farmed crops, ran mills, and leased lands. Some owned potteries and other businesses. Their economic self-sufficiency allowed them to fund charitable work and maintain their institutions.

What were stylite monks and what did their practice involve?

Stylite monks, like Symeon the Stylite, practiced extreme asceticism by living atop tall columns for years. This unusual devotion symbolized spiritual detachment and a desire for divine communion. These figures drew public attention and inspired a wider ascetic movement, emphasizing mystical personal experience.

How did monasteries interact with imperial politics?

Monasteries influenced both church and state affairs. While emperors granted them privileges, monasteries were also targeted during periods like the iconoclasm of the 8th and 9th centuries. Despite persecution, they remained respected and influential institutions throughout Byzantine history.

What are the Byzantine Empire’s Most Important Accomplishments?