Scipio Aemilianus (185 BC – 129 BC)

Scipio Aemilianus (185–129 BC), also known as Scipio Africanus the Younger, was a Roman general and statesman known for his victories in the Third Punic War and the Numantine War.

Early Life and Family Heritage

Scipio Aemilianus hailed from one of Rome’s most illustrious families. Born as the second son of Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, the celebrated commander who triumphed in the Third Macedonian War, and Papiria Masonis, Scipio was steeped in military and political tradition from a young age.

His path took a pivotal turn when he was adopted by his first cousin, Publius Cornelius Scipio, the son of Scipio Africanus, Rome’s hero of the Second Punic War. This adoption linked him to the legacy of defeating Hannibal, solidifying his ties to Roman military glory. After his adoption, he took the name Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus while retaining “Aemilianus” to reflect his original lineage.

Military Beginnings: Third Macedonian War

Scipio’s first exposure to warfare came during the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC), where he accompanied his father, Lucius Aemilius Paullus, on campaign in Greece. At just 17 years old, Scipio demonstrated remarkable bravery during the aftermath of the Battle of Pydna, where he was thought missing after pursuing enemies into dangerous territory. His eventual return to camp, bloodied and triumphant, marked him as a young man destined for greatness. Even in these early days, his charisma and skill earned him admiration from soldiers and commanders alike.

The Numantine War: Early Challenges

In 151 BC, the Numantine War in Spain posed significant difficulties for Rome. When recruitment faltered due to the conflict’s reputation for heavy losses, Scipio stepped forward as a military tribune. His example encouraged others to join the campaign.

Under Lucius Licinius Lucullus, Scipio earned a mural crown, an honor awarded for being the first to scale a besieged city’s walls. He further distinguished himself by reportedly winning spolia opima, the prestigious prize for defeating an enemy leader in single combat, cementing his reputation as a fearless and skilled warrior.

The Third Punic War: The Fall of Carthage

The ruins of Carthage, located in modern-day Tunisia. Tiberius served as an officer under Scipio Aemilianus during the Third Punic War, when the city was razed.

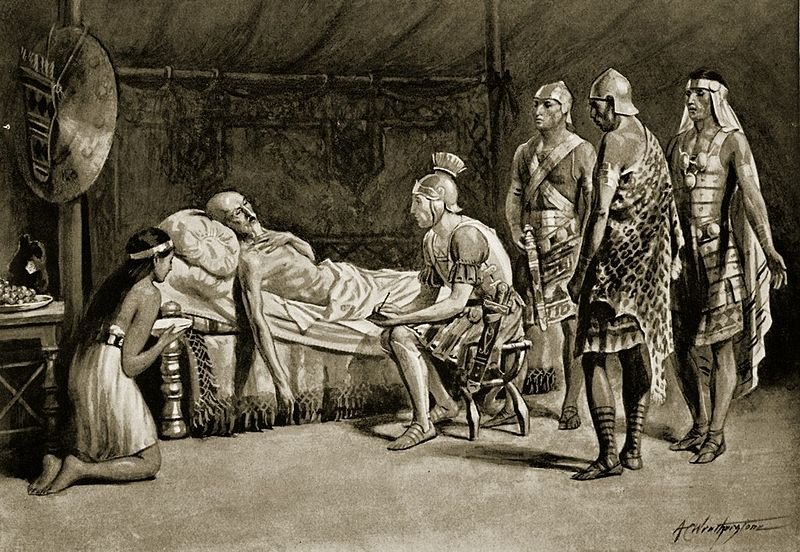

Despite being subdued in the Second Punic War, Carthage remained a symbol of Roman fear and enmity. Encouraged by Cato the Elder‘s infamous refrain, “Carthage must be destroyed,” Rome sought an excuse to annihilate its ancient rival. In 149 BC, Carthage’s self-defense against encroachment by Masinissa, the Numidian king, was construed as a breach of Roman treaties, triggering the Third Punic War.

As a military tribune, Scipio’s leadership was critical in the early phases of the siege of Carthage. He salvaged Roman forces during critical moments, such as repelling night attacks and orchestrating retreats when Roman assaults faltered. His tactical acumen and bravery won him recognition and, in 147 BC, election as consul, bypassing the minimum age requirement due to public demand.

Scipio Aemilianus, also known as Scipio Africanus the Younger, was a Roman general and statesman known for his victories in the Third Punic War and the Numantine War.

Upon assuming command, Scipio imposed a brutal blockade, systematically starving the city into submission. After months of resistance, Carthage fell in 146 BC. Scipio razed the city, enslaving 50,000 survivors and fulfilling Rome’s long-held desire for its destruction. The myth that Carthage was salted to prevent regrowth is now considered apocryphal. This victory earned Scipio the honorific title “Africanus”, linking him indelibly to Carthage’s demise.

In 149 BC, Carthage’s self-defense against encroachment by Masinissa, the Numidian king, was construed as a breach of Roman treaties, triggering the Third Punic War. Image: Scipio at the deathbed of Masinissa

READ MORE: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the Punic Wars

The Numantine War: Final Triumphs

In 134 BC, Scipio was recalled to Spain during the protracted and disastrous Numantine War, which had humiliated Rome for nearly a decade. Numantia, a Celtiberian stronghold with formidable natural defenses, had repelled Roman attempts at subjugation. Recognized for his past successes, Scipio was elected consul again and entrusted with restoring Roman dominance.

Scipio’s first move was to reform the demoralized Roman army, banning luxuries, enforcing rigorous training, and reinstating discipline. After neutralizing nearby tribes who supported Numantia, he constructed an intricate system of fortifications around the city, effectively starving it into surrender. The siege culminated in Numantia’s destruction in 133 BC, earning Scipio the additional title of “Numantinus”.

Political Career: Opposition and Controversy

In 142 BC, Scipio served as censor, tasked with upholding Rome’s moral and social values. His tenure was marked by efforts to curb excesses and restore traditional Roman virtues. He faced criticism and even accusations of treason, likely stemming from political rivalries.

Scipio’s relationship with the Gracchi family—notably his brother-in-law Tiberius Gracchus—was complicated. Initially supportive, he later opposed Tiberius’ populist land reforms, which aimed to redistribute public land to Rome’s poor. Scipio’s public criticism of Tiberius after his assassination further alienated him from the Roman populace.

As tensions over the Gracchian reforms escalated, Scipio championed the rights of Rome’s Italian allies, who were adversely affected by land redistribution efforts. His advocacy, while principled, fueled rumors that he sought to undermine the reforms entirely. This unpopularity coincided with his untimely death in 129 BC.

Death and Rumors of Assassination

Scipio’s death remains shrouded in mystery. Found lifeless in his bed, speculation abounded. Some blamed political rivals, including supporters of the Gracchi; others suggested poisoning or even suicide. Despite the ambiguity, his death marked the end of a towering figure in Roman history.

Patron of Culture and Philosophy

Scipio Aemilianus was not only a military and political leader but also a patron of learning. He surrounded himself with intellectual luminaries, including the Greek historian Polybius and the Stoic philosopher Panaetius. His “Scipionic Circle” fostered a fusion of Greek and Roman thought, influencing Roman culture profoundly. Scipio’s admiration for Greek philosophy, art, and literature reflected his philhellenic tendencies, though this sometimes invited criticism from traditionalists.

Personal Traits and Legacy

Scipio was known for his strategic brilliance, discipline, and unwavering commitment to Roman ideals. His ability to balance martial prowess with intellectual pursuits made him a paragon of Roman virtue. However, his political stances and outspokenness occasionally alienated him from both allies and the general populace.

A poignant episode from Scipio’s life occurred after the sack of Carthage when he reportedly quoted Homer’s Iliad, lamenting the inevitable decline of even the mightiest civilizations. This moment of introspection underscored his awareness of Rome’s own vulnerabilities, revealing a contemplative side to the otherwise indomitable general.

Influence on Rome and Beyond

Scipio’s legacy extended beyond his military conquests. By integrating Greek intellectual traditions into Roman society, he helped shape the cultural trajectory of the Republic. His destruction of Carthage and Numantia solidified Rome’s dominance, but his philosophical reflections and patronage of learning ensured his influence endured in realms beyond warfare.

What did Aristotle think about the Constitution of Carthage?

Frequently Asked Questions

What was his role in the Third Punic War?

He commanded Roman forces to victory, overseeing the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC, marking the end of the war.

What achievements define his military career?

He earned distinction early in the Third Macedonian War, decisively defeated Carthage, and later subdued Numantia, demonstrating superior strategic and leadership skills.

Catapulta by English painter Edward Poynter depicts a Roman siege engine in operation during the siege of Carthage in the Third Punic War.

What was his relationship with cultural and intellectual figures?

A patron of the arts and philosophy, he was closely associated with the historian Polybius and Stoic philosopher Panaetius, fostering a philhellenic cultural circle.

1797 engraving representing Scipio Aemilianus before the ruins of Carthage in 146 BC in the company of his friend Polybius

What role did he play in Roman politics?

As a censor, he promoted traditional Roman values, opposed the populist reforms of Tiberius Gracchus, and supported Rome’s aristocracy against radical land reforms.

What are the key controversies surrounding his death?

While ancient sources suggest possible murder or suicide, modern historians lean toward natural causes, given the lack of concrete evidence for foul play.

What was his philosophy on human affairs?

Reflecting on the destruction of Carthage, Scipio foresaw the eventual fall of all great powers, including Rome, as recounted by Polybius.