The Cylinders of Nabonidus

The Cylinders of Nabonidus are ancient cuneiform inscriptions commissioned by Nabonidus, the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, who reigned from 556 to 539 BCE. These inscriptions, found on clay cylinders, provide significant insight into Nabonidus’s reign, religious beliefs, and building projects. Among these are the notable Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar and the Nabonidus Cylinders from Ur, each detailing various aspects of his rule, particularly his dedication to temple restoration and his complex relationship with Babylonian deities.

These artifacts not only highlight the religious and political environment of his time but also hold valuable information about the evolution of Mesopotamian religious practices, which was later reflected in the inscriptions of Cyrus the Great, the Persian ruler who conquered Babylon.

Nabonidus’s Background and Reign

Nabonidus, meaning “May Nabu be exalted,” was the final ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, reigning from 556 BC until Babylon fell to Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE. Image: Nabonidus, detail of a stele in the British Museum, probably from Babylon, Iraq

Nabonidus’s rise to power marked a significant shift in Babylonian tradition. Unlike his predecessors, Nabonidus showed an unusual preference for the moon god Sin rather than the traditional state god Marduk, a decision that stirred controversy among Babylon’s elite. Sin, worshiped primarily in the cities of Harran and Ur, was the deity most closely associated with Nabonidus’s family background, as his mother had been a priestess dedicated to Sin.

Nabonidus’s religious focus was unconventional, as most Neo-Babylonian kings prioritized Marduk and were expected to honor him above other gods to uphold the balance of power within the empire. Nabonidus’s promotion of Sin likely contributed to unrest among the Babylonian priesthood and nobility, who perceived his devotion as undermining the established religious and social order.

Map of the Neo-Babylonian Empire under its final king Nabonidus

Nabonidus spent a significant portion of his reign away from Babylon, living for nearly ten years in Tayma, an oasis in northwest Arabia, while his son Belshazzar governed in his absence. Nabonidus’s retreat to Tayma has long puzzled historians and sparked various theories, including suggestions that he sought refuge to avoid conflicts in Babylon or pursued religious solitude. His absence allowed Belshazzar to act as co-regent, which may have fostered political tensions, particularly with the priesthood, who were already displeased with Nabonidus’s favoritism toward Sin.

The Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar

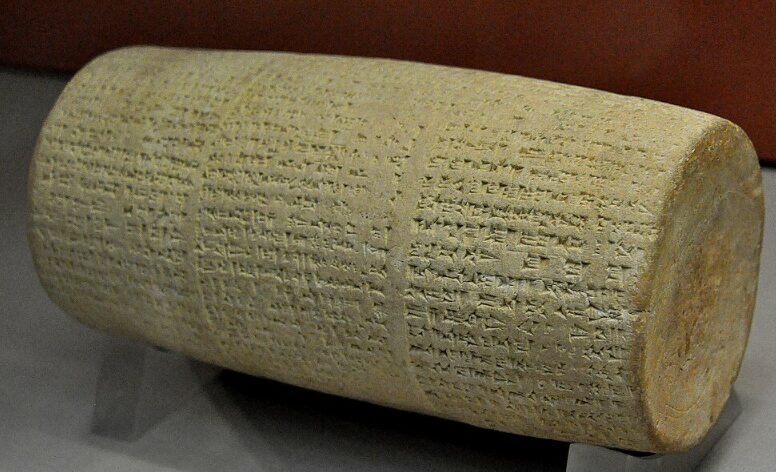

The inscriptions from the Cylinders of Nabonidus document King Nabonidus’ religious devotion, temple restorations, and prayers for his son, Belshazzar. Image: The Nabonidus Cylinder of Sippar on display in the British Museum

The Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar, a clay cylinder inscribed with a long text, describes Nabonidus’s restoration of three major temples: the temple of Sin in Harran, the sanctuary of Anunitu (a warrior goddess) in Sippar, and the temple of Šamaš, the sun god, also in Sippar.

Nabonidus’s focus on repairing these temples aligns with his religious devotion to Sin and a broader initiative to restore temples across the empire. The restoration of Sin’s temple in Harran held personal significance for Nabonidus, as this city was central to the worship of Sin and to his family heritage.

The Sippar Cylinder emphasizes Nabonidus’s intention to honor and preserve sacred spaces, portraying him as a pious ruler fulfilling his duty to the gods. However, his attention to deities outside the Babylonian mainstream—particularly Sin—further illustrates his complicated relationship with Babylonian religious traditions.

The cylinder’s text reflects Nabonidus’s efforts to repair temples and renew religious practices, despite the underlying controversy surrounding his preferences. The inscription also serves as a symbolic gesture, reaffirming his connection to the divine and his desire to legitimize his rule.

The Nabonidus Cylinders from Ur

Cylinder of Nabonidus from the temple of God Sin at UR, Mesopotamia.

The Nabonidus Cylinders from Ur are a set of four clay cylinders that contain the foundation text for a ziggurat called E-lugal-galga-sisa, which belonged to the temple of Sin in Ur. In this text, Nabonidus describes the extensive repairs he made to the ziggurat, underscoring his commitment to restoring religious structures dedicated to Sin. This inscription, dated around 540 BCE, is thought to be Nabonidus’s last building record before his eventual defeat by Cyrus the Great. It is also significant for its theological themes, as it reflects Nabonidus’s syncretism, or the blending of different religious beliefs, by incorporating aspects of Marduk and Nabu, alongside his devotion to Sin.

Late Assyrian seal depicting a worshipper between Nabu and Marduk, standing on the dragon Mušḫuššu, 8th century BCE.

This form of religious syncretism may have been Nabonidus’s attempt to unify Babylonian religious traditions, reconciling his allegiance to Sin with the wider Babylonian pantheon revered by his subjects.

By blending elements of Sin, Marduk, and Nabu, Nabonidus perhaps sought to placate the Babylonian priesthood and reduce opposition to his rule, though this effort appears to have had limited success.

The Ur cylinders are also noteworthy for their mention of Belshazzar, Nabonidus’s eldest son. The inscription includes a prayer for Belshazzar, requesting that he be granted reverence for the gods and protection against any ritual mistakes. This reference to Belshazzar is historically significant, as it links Nabonidus’s reign to the later biblical narrative of Belshazzar in the Book of Daniel.

READ MORE: Greatest Ancient Mesopotamian Cities

Historical Context of the Cylinders’ Discovery

The Nabonidus Cylinders from Ur were discovered in 1854 by British archaeologist J.G. Taylor. He found four identical cylinders in the foundation of a ziggurat at Ur, each bearing the same inscription.

It was common practice in Mesopotamian construction to place multiple copies of significant inscriptions in different parts of a building’s foundation. This practice ensured the preservation of royal records and sanctified the structure with the king’s words.

In 1881, another important discovery related to Nabonidus was made by Assyriologist Hormuzd Rassam at Sippar, where he unearthed a clay cylinder of Nabonidus in the temple of the sun god Šamaš. This cylinder, excavated from Nabonidus’s palace at Sippar, is now housed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, with a replica in the British Museum.

Assyriologist Hormuzd Rassam

The Sippar Cylinder is especially intriguing because it was inscribed after Nabonidus’s return from Tayma, likely during his thirteenth year as king, before the Persian ruler Cyrus the Great launched his campaign against Babylon. In this text, Nabonidus portrays Cyrus as a divinely sanctioned conqueror, foreshadowing the themes that would later appear in the Cyrus Cylinder, which depicts Cyrus as a restorer of order and harmony. The Sippar Cylinder demonstrates Nabonidus’s awareness of Cyrus’s growing power and seems to suggest an attempt to frame Cyrus’s actions as part of a divine plan.

Thematic Significance and Legacy of the Nabonidus Cylinders

Cylinder of Nabonidus from the temple of Shamash at Larsa, Mesopotamia.

The Nabonidus Cylinders from Sippar and Ur incorporate themes found in earlier Babylonian foundation texts, while also introducing motifs that would influence later inscriptions, most notably the Cyrus Cylinder.

In the Sippar Cylinder, Nabonidus uses a lengthy titulary, or royal title, to affirm his status, and the text includes a narrative of a god angered by the neglect of his shrine. This god, reconciled with the people, commands Nabonidus to restore the temple, and Nabonidus responds by increasing offerings and demonstrating his piety. The text culminates with prayers for Nabonidus’s own well-being and blessings for his son Belshazzar.

The similarities between the Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar and the later Cyrus Cylinder suggest that Nabonidus’s inscriptions may have inspired Cyrus or his scribes. Both cylinders emphasize a divine mandate, presenting the ruler as a pious servant carrying out the gods’ will.

Additionally, both documents reflect a belief in the importance of temple restoration as a means of legitimizing rule. Cyrus’s adoption of these themes indicates a continuity of religious and political symbolism in Mesopotamian kingship, where rulers derived authority from their perceived relationship with the gods and their ability to restore divine order.

Impact on Modern Understanding of Babylonian Religion and Kingship

The Nabonidus Cylinders provide scholars with valuable insights into the religious practices and political dynamics of ancient Babylon. Nabonidus’s devotion to Sin, his emphasis on temple restoration, and his attempts at religious syncretism reveal the complexities of Babylonian kingship and the delicate balance that rulers needed to maintain with the priesthood and the nobility.

His focus on Sin, despite the risks, demonstrates his willingness to challenge traditional Babylonian religious norms, though it ultimately may have undermined his rule.

Moreover, the references to Belshazzar in the Nabonidus Cylinders add a historical dimension to the biblical narrative in the Book of Daniel, providing evidence of Belshazzar’s existence and his role as Nabonidus’s co-regent.

While Belshazzar was never officially king, his position as Nabonidus’s heir is clearly established in these texts. This connection has been of particular interest to historians and biblical scholars, as it corroborates certain elements of the biblical story while providing a more nuanced understanding of Belshazzar’s status.

Conclusion

The Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar and the Nabonidus Cylinders from Ur are more than mere inscriptions; they represent Nabonidus’s unique approach to kingship and his enduring legacy in Mesopotamian history. By emphasizing his dedication to temple restoration, his loyalty to Sin, and his complex religious ideology, these artifacts shed light on the last years of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and the political challenges Nabonidus faced. His efforts to reconcile various religious traditions, while maintaining his devotion to Sin, underscore the diversity of religious thought in Mesopotamia and the ways in which rulers sought to legitimize their power.

These cylinders also anticipate the ideological framework adopted by Cyrus the Great, who, after conquering Babylon, used similar language to portray himself as a divinely guided ruler committed to restoring sacred sites. Thus, the Nabonidus Cylinders not only inform us about Nabonidus’s reign but also illustrate the lasting influence of Babylonian religious and political traditions on subsequent empires. By preserving these inscriptions, Nabonidus ensured that his vision of kingship would survive, allowing modern historians to better understand the complex interplay between religion, politics, and culture in ancient Mesopotamia.

Frequently Asked Questions

The Cylinders of Nabonidus are ancient clay cylinders inscribed with cuneiform texts by Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon (556-539 BC).

What are the Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar and the Nabonidus Cylinders from Ur?

These are cuneiform-inscribed clay cylinders from the reign of Nabonidus, the last ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. They document Nabonidus’s efforts to restore temples dedicated to major Babylonian deities and provide insight into his religious beliefs.

What temples are mentioned in the Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar?

The Sippar Cylinder details Nabonidus’s restoration of three temples: the sanctuary of Sin, the moon god, in Harran; the sanctuary of Anunitu, a warrior goddess, in Sippar; and the temple of Šamaš, the sun god, also in Sippar.

Why was Nabonidus’s focus on the god Sin controversial?

Nabonidus’s devotion to Sin, rather than the traditional Babylonian state god Marduk, was controversial among the Babylonian elites. This preference possibly contributed to political instability during his rule.

What is the significance of the Nabonidus Cylinders from Ur?

The Ur cylinders contain the foundation text for a ziggurat dedicated to Sin and reflect Nabonidus’s achievements in temple restoration. These texts also showcase religious syncretism by blending aspects of Sin, Marduk, and Nabu.

READ MORE: The Conflict between Marduk and Tiamat

Who is Belshazzar, as mentioned in the Ur cylinders?

Belshazzar was Nabonidus’s eldest son and co-regent during his time in Arabia. The cylinders include a prayer for Belshazzar, asking the gods to bless him with reverence and prevent cultic errors.

How were the Nabonidus Cylinders from Ur discovered?

J.G. Taylor discovered four identical cylinders in the foundation of Ur’s ziggurat in 1854. This practice of placing identical inscriptions in different parts of a foundation was common in Mesopotamian architecture to preserve the king’s words.

What was Assyriologist Hormuzd Rassam’s discovery in 1881?

Rassam found a Nabonidus cylinder at the temple of the sun in Sippar. This cylinder, now in the Pergamon Museum, was written after Nabonidus’s return from Arabia, prior to the Persian invasion by Cyrus the Great.

How does the Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar relate to the later Cyrus Cylinder?

The Sippar Cylinder includes themes like a god angered by the neglect of his shrine, a king restoring the temple, and a prayer for divine favor. These themes are echoed in the Cyrus Cylinder, where Cyrus is depicted as restoring order under divine guidance.

What themes are included in the Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar?

The cylinder includes a long titulary for Nabonidus, a story of divine anger and reconciliation, Nabonidus’s restoration work, and prayers for divine favor, which portray him as a devout and legitimate ruler.

What do the Nabonidus cylinders reveal about Nabonidus’s reign?

The cylinders show Nabonidus’s dedication to temple restoration, his devotion to Sin, his hopes for his son Belshazzar, and his efforts to blend various religious traditions in Babylon, contributing to our understanding of Babylonian kingship and religion.