Who are the major Chthonic Deities in Greek Religion and Mythology?

In Greek religion and mythology, chthonic deities are those associated with the earth, the underworld, and the life-sustaining forces of agriculture, growth, death, and rebirth.

The term chthonic, derived from the Greek khthon (earth or ground), describes gods, goddesses, spirits, and creatures linked to the subterranean realm or the forces within the soil, as well as the rituals and beliefs surrounding them.

Unlike the Olympian gods, who were worshipped primarily in temples and associated with the sky, chthonic deities were often venerated in sacred pits, caves, and outdoor sanctuaries, symbolizing their close connection to the earth.

Below, World History Edu presents some of the major chthonic deities in Greek religion and mythology and the unique roles they played in ancient Greek belief systems.

The term “chthonic” comes from the Greek word khthon, meaning earth or soil, specifically referring to what lies beneath the earth’s surface.

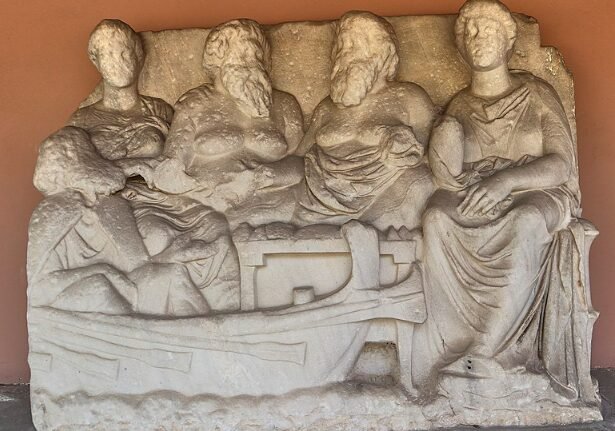

Chthonic describes elements associated with the underworld, like chthonic gods, rituals, and cults. Unlike the Olympic gods, who are linked to the sky, chthonic deities are connected to the underground realm and aspects of agriculture, as they govern the forces within the soil essential for planting and growth. Image: A 320 BC relief from Lysimachides’ grave shows two men and two women seated together as Charon, the underworld ferryman, approaches to escort him to the afterlife.

Hades: The King of the Underworld

Hades/Serapis with Cerberus, a mid-2nd century AD statue from the Sanctuary of Egyptian Gods in Gortyna.

Hades, also known as Pluto in later Roman mythology, is the principal ruler of the underworld and is often considered the archetypal chthonic deity.

As the son of Cronus and Rhea and brother to Zeus and Poseidon, Hades is one of the major gods of the Greek pantheon, though he resides in the underworld rather than on Mount Olympus. His primary role is to govern the realm of the dead, where souls reside after leaving the mortal world.

Hades’ kingdom includes rivers like the Styx and Acheron, the Elysian Fields (a paradise for favored souls), and the gloomy fields of Asphodel.

In myths, Hades is a complex figure. He is neither purely malevolent nor benevolent; rather, he is a neutral and just ruler, maintaining balance between life and death.

Hades abducting Persephone, fresco in the small royal tomb at Vergina, Macedonia, Greece, circa 340 BC

One of the most famous myths involving Hades is his abduction of Persephone, daughter of Demeter. This myth of Persephone’s cyclical descent to and return from the underworld forms the basis of the ancient Greek understanding of seasonal change, especially the fall and rebirth of vegetation.

Worshippers offered sacrifices to Hades at night, often with dark-hided animals, as his role as the god of death and the underworld linked him closely with the mysterious and hidden.

Persephone: Queen of the Underworld

Statue of the syncretic deity Persephone-Isis holding a sistrum, located in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete.

Persephone, the daughter of Demeter and Zeus, is central to chthonic mythology as both the goddess of spring and the queen of the underworld.

Her duality as a goddess who moves between the realms of life and death is perhaps one of the most profound examples of chthonic association in Greek religion. The myth of Persephone’s abduction by Hades and her subsequent role as his wife illustrates the Greek understanding of death and rebirth.

Heintz Joseph the Elder, The Rape of Persephone, circa 1595

Persephone spends part of each year in the underworld with Hades and part above ground with her mother, Demeter. Her movement between these realms symbolizes the agricultural cycle of growth and dormancy: when she is in the underworld, the earth becomes barren (fall and winter), and when she returns, vegetation flourishes again (spring and summer). As such, Persephone is associated with vegetation, fertility, and the renewal of life, despite her ties to the underworld.

Ancient rites in her honor, such as the Eleusinian Mysteries, emphasized her role in the mysteries of life, death, and rebirth, with initiates seeking to gain insight into the afterlife and to secure favor for themselves in the underworld.

Persephone’s return to the land of the living ushered in the spring season and bountiful harvests. Image: The Return of Persephone, 1891, by Frederic Leighton

Demeter: Goddess of Agriculture and the Harvest

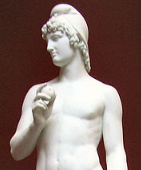

A marble statue of Demeter, National Roman Museum

Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, fertility, and the harvest, holds a unique position as a deity connected both to the chthonic and Olympian realms.

As the mother of Persephone, she experiences profound grief when her daughter is taken to the underworld by Hades, leading to her own association with death and rebirth. Demeter’s mourning for Persephone symbolizes the withering of crops in the winter, while her joy upon her daughter’s return heralds the renewal of growth and the onset of spring.

Demeter’s connection to the chthonic realm is deepened through her role as a goddess who oversees the processes of planting, growing, and harvesting, all of which take place within or upon the earth.

Her most significant cult was centered at Eleusis, where she and Persephone were venerated in the Eleusinian Mysteries, one of the most significant and secretive cultic practices in ancient Greece. These mysteries offered initiates a glimpse into the cycle of life and death, and their rituals underscored Demeter’s dual association with life-giving growth and the inevitability of mortality.

Hecate: Goddess of Magic, Crossroads, and the Night

Hecate, Greek goddess of the crossroads; drawing by Stéphane Mallarmé in Les Dieux Antiques, nouvelle mythologie illustrée in Paris, 1880

Hecate is a multifaceted goddess associated with magic, witchcraft, crossroads, and the night. Though she is sometimes included among the Olympian deities, her role as a chthonic figure is more prominent due to her associations with ghosts, necromancy, and the underworld.

Hecate is also connected to boundaries, thresholds, and transitions, especially between the worlds of the living and the dead. She was often depicted holding torches or keys, symbols of her power to guide souls through darkness and to unlock the secrets of the spirit world.

The Hecate Chiaramonti, a Roman sculpture depicting the triple-bodied Hecate, inspired by a Hellenistic original (Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums).

Hecate’s role in the Persephone myth reinforces her chthonic character. In some versions of the story, Hecate assists Demeter in searching for Persephone and later becomes Persephone’s companion in the underworld. In her role as a goddess of witchcraft, Hecate was venerated by those who practiced magic, and her rituals often involved offerings at crossroads or the use of black animals.

She was also associated with the household and protector of doors and gates, indicating her role in guarding against evil spirits. Her character combines elements of mystery and power, making her one of the more enigmatic chthonic deities in Greek mythology.

The Erinyes (Furies): Goddesses of Vengeance

In Greek mythology, the Erinyes, or Furies, are chthonic goddesses of vengeance who pursue those guilty of serious crimes, especially those against family. Image: A red-figure bell-krater from 330 BC depicts Orestes at Delphi, protected by Athena and Pylades, surrounded by Erinyes and oracle priestesses.

The Erinyes, also known as the Furies, are chthonic goddesses of vengeance who reside in the underworld and are primarily responsible for punishing those who commit crimes against family members, particularly murders.

Born from the blood of Uranus when he was castrated by his son Cronus, the Furies represent primal forces of retribution and moral justice. They are often depicted as fierce and terrifying figures with serpents in their hair and blood dripping from their eyes, emphasizing their relentless pursuit of justice.

The Erinyes were especially feared by the Greeks, as their wrath was unyielding, and they could not be easily appeased once summoned. Although they were considered goddesses of punishment, the Erinyes were also seen as agents of balance and order.

By punishing moral transgressions, they helped maintain social and familial harmony. Sacrifices and offerings were sometimes made to appease them, especially by those who feared their wrath or sought their assistance in achieving justice. As such, the Erinyes are quintessential chthonic deities, embodying both the darkness and order associated with the earth and the underworld.

The Erinyes are known for their relentless pursuit of justice and are feared for their unyielding wrath.

In the story of Orestes, son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, the Erinyes play a pivotal role. After Orestes avenges his father by killing his mother, Clytemnestra, the Erinyes relentlessly pursue him to exact punishment for the crime of matricide. Haunted and tormented by their pursuit, Orestes ultimately seeks refuge in Athens, where he is put on trial. Goddess Athena intervenes and, through the establishment of a trial by jury, acquits Orestes, symbolizing the shift from personal revenge to structured legal justice in Greek culture.

The Remorse of Orestes, where he is surrounded by the Erinyes, by French academic painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1862

Gaia: The Primordial Earth Mother

Gaea by German painter Anselm Feuerbach, 1875 ceiling painting, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

Gaia, the primordial goddess of the earth, is one of the oldest and most revered deities in Greek mythology. As the embodiment of the earth itself, she is both a personification of the land and a powerful chthonic force responsible for life and creation.

Gaia gave birth to the Titans, the Giants, and various other beings, positioning her as the ancestral mother of many gods and creatures in Greek mythology.

Although not typically associated with the underworld in the same way as Hades or Persephone, Gaia’s connection to the earth places her firmly within the chthonic sphere. In Greek cosmology, she is often involved in the stories of rebellion and retribution, as seen when she allies with the Giants against the Olympians to avenge her children, the Titans.

Gaia was worshipped in various locations across Greece, often with offerings made directly into the earth to honor her as the source of life. Her dual nature as a life-giver and a force of vengeance connects her to both the nurturing and destructive aspects of the chthonic domain.

Family tree of Greek goddess Gaia

Thanatos: Personification of Death

Hypnos and Thanatos: Sleep and His Half-Brother Death, by English painter John William Waterhouse, 1874.

Thanatos is the personification of death in Greek mythology. As the twin brother of Hypnos (Sleep) and son of Nyx (Night), Thanatos represents the peaceful, inevitable end that awaits all living things. Unlike Hades, who governs the underworld and its souls, Thanatos’s role is simply to usher mortals from life to death. He is often depicted as a winged youth carrying a sword or an extinguished torch, symbolizing the end of life’s flame.

Although Thanatos does not have a large mythological presence compared to other gods, he is nonetheless a key figure in Greek conceptions of mortality. As a chthonic figure, Thanatos embodies the inevitable and impartial nature of death, distinguishing him from the more complex role of Hades.

In some myths, Thanatos is tricked or delayed, symbolizing humanity’s desire to evade death, but ultimately, his role as the personification of death is absolute.

Charon: The Ferryman of the Dead

Attic red-figure lekythos by the Tymbos Painter depicts Charon welcoming a soul aboard, c. 500–450 BC.

Charon is a lesser-known but essential chthonic figure who serves as the ferryman of the dead in Greek mythology. His role is to transport the souls of the deceased across the river Styx (or sometimes the Acheron) to reach the underworld.

Charon is often depicted as an elderly, grim figure who demands a coin as payment for passage. This coin, usually placed in the mouth or on the eyes of the deceased, was essential for entering Hades’ realm.

Charon’s role emphasizes the Greeks’ belief in proper burial rituals and the importance of guiding souls to the afterlife. Without the required coin, a soul would be left to wander on the banks of the river, unable to find peace in the underworld.

Though Charon is not a deity in the conventional sense, he is a significant chthonic figure who reinforces the concept of transition and the importance of ritual in Greek funerary practices.

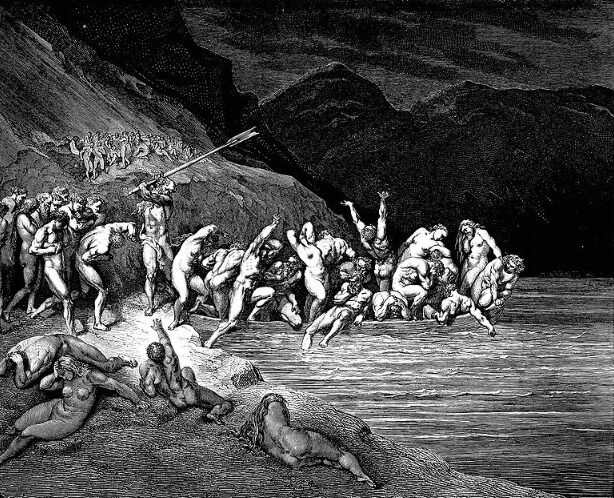

In the Divine Comedy, Charon drives unwilling sinners onto his boat, striking them with his oar (French artist Gustave Doré, 1857).

Nyx: Goddess of the Night

Image: Roman-era bronze statuette of Nyx velificans or Selene (Getty Villa)

Nyx, the personification of night, is an ancient and powerful figure in Greek mythology. She is one of the primordial deities, born from Chaos, and is considered one of the earliest beings in the Greek cosmological hierarchy.

Nyx is the mother of various deities associated with dark and mysterious forces, including Thanatos (Death), Hypnos (Sleep), and the Moirai (Fates), which solidifies her status as a chthonic goddess linked to the unknown and the inevitable aspects of existence.

Nyx’s influence is far-reaching, and even Zeus is said to have feared her. Although she does not dwell in the underworld, Nyx’s association with the night and her children’s roles as agents of fate and death place her firmly within the chthonic realm. Nyx was revered as a goddess of mysteries, often evoked in rituals that emphasized the unknowable and the supernatural aspects of the universe.

Nyx family tree

The Moirai (Fates): Goddesses of Destiny

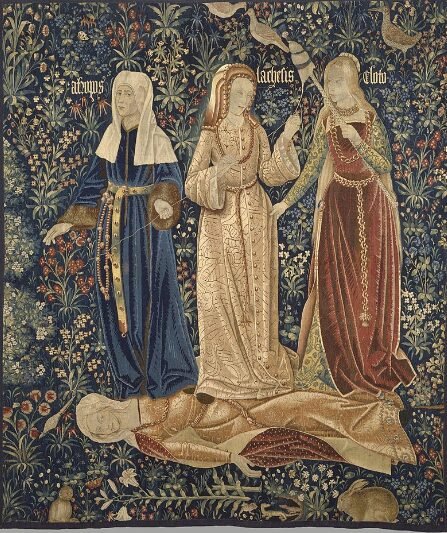

The three Moirai, or the Triumph of death, Flemish tapestry, c. 1520 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The Moirai, or Fates, are three sisters—Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos—who control the destiny of all beings, including gods. As chthonic deities, they govern the cycle of life and death by weaving, measuring, and cutting the thread of life, symbolizing the beginning, duration, and end of each person’s life. Clotho spins the thread, Lachesis measures it, and Atropos cuts it, signifying death. Their power over fate is absolute, and not even the gods can escape their decrees.

The Moirai’s role as arbiters of destiny places them within the chthonic sphere, emphasizing their connection to life’s inescapable cycles. Their presence in Greek mythology underscores the importance of accepting one’s fate, as their actions are beyond human or divine influence. Although the Moirai were not widely worshipped, they were deeply respected as guardians of order, particularly the order of life and death.

Conclusion

Chthonic deities in Greek religion and mythology represent a diverse and complex spectrum of gods, spirits, and personifications connected to the earth, the underworld, and the forces of death and rebirth.

Figures like Hades, Persephone, and Demeter exemplify the relationship between life’s cyclical nature and agricultural fertility, while others, like Hecate and the Erinyes, embody mystery, vengeance, and moral order. Lesser-known but equally important figures, such as Charon and Thanatos, reinforce the Greek emphasis on rituals and respect for the afterlife.

These deities highlight the ancient Greek understanding of the world as a balanced interplay between life and death, fertility and decay, growth and retribution. While some of these deities were feared, others were revered and invoked for protection and blessings.

Through their myths and the cult practices associated with them, chthonic deities provided a framework for comprehending the mysteries of the earth, the inevitability of death, and the hope for renewal, reflecting fundamental aspects of the human experience that remain relevant in cultural narratives to this day.

Frequently Asked Questions

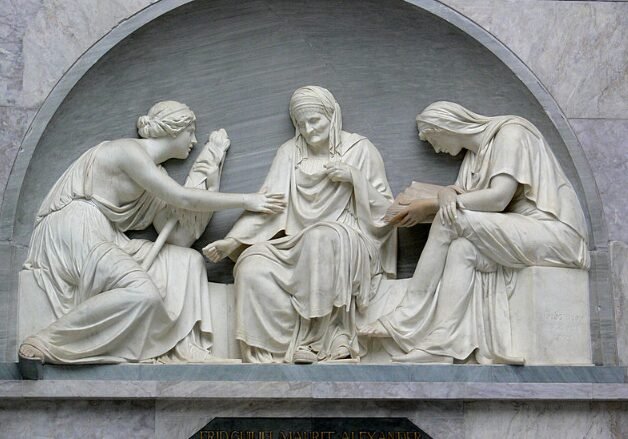

The three Moirai, relief, grave of Alexander von der Mark [de] by German Prussian sculptor Johann Gottfried Schadow (Old National Gallery, Berlin)

What do the terms chthonic and ouranic (Olympian) represent in Ancient Greek religion?

Chthonic and ouranic represent different divine associations: chthonic is connected to the underworld and agriculture, while ouranic relates to the heavens. They are not strict opposites but rather part of a spectrum of divine attributes.

Which deities are commonly associated with chthonic qualities?

Hades, Persephone, and the Erinyes (Furies) are commonly associated with chthonic qualities due to their close ties to the underworld.

Can any god be considered chthonic?

Yes, many gods can be considered chthonic in specific contexts. For example, Demeter and Hermes, though Olympian gods, are associated with chthonic aspects related to agriculture and the underworld.

What is an epithet in Ancient Greek religion, and how does it relate to chthonic deities?

An epithet is a descriptive “surname” used to highlight specific attributes or domains of a deity. Chthonios or chthonia often follows the names of gods or goddesses to emphasize their underworld or agricultural associations, like Hermes Chthonios.

Why doesn’t Charon require a chthonic epithet?

Charon, as the underworld’s ferryman, is inherently linked to the chthonic realm, making an additional chthonic epithet unnecessary.

How do Persephone’s associations with life and death reflect her chthonic nature?

Persephone’s annual descent to the underworld and return to the earth’s surface symbolize the seasonal cycle, associating her with both life and death, as well as agriculture.

What elements reflect the distinctions between chthonic and ouranic sacrificial practices?

Ouranic sacrifices took place on raised altars outdoors, used wine as libations, and directed offerings toward the sky, while chthonic sacrifices involved burning dark-hided animals entirely, with offerings directed into the ground on low altars or pits.

Why was honey used in chthonic sacrifices instead of incense or wine?

Honey, a downward-pouring substance, was used because incense and wine release upward smoke or flow, which would be contrary to the chthonic ritual’s goal of reaching gods beneath the earth.

What is the scholarly debate around the terms chthonic and ouranic?

Some scholars argue that the strict division between chthonic and ouranic is overly rigid and doesn’t reflect the fluid nature of Greek religious practices. Scott Scullion suggests using chthonic as a descriptive term within a broader context rather than an absolute category.