The Siege of Carthage in 146 BC

The Siege of Carthage, the primary engagement of the Third Punic War (149–146 BC), marked the final confrontation between the Roman Republic and Carthage. Lasting nearly three years, it ended with the total destruction of Carthage, a defining moment in ancient history that solidified Roman dominance in the western Mediterranean. The battle, set against the backdrop of Carthage’s waning influence and Rome’s imperial ambitions, demonstrated the stark realities of Roman militarism and Carthaginian desperation.

READ MORE: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the Punic Wars

Prelude to the Siege

The origins of the Third Punic War lay in the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), which concluded with Carthage’s defeat and subjugation under Rome. Stripped of its overseas territories and severely restricted militarily, Carthage was left politically subordinate to Rome. Despite these restrictions, Carthage rebuilt its economy, becoming prosperous yet vulnerable to external threats.

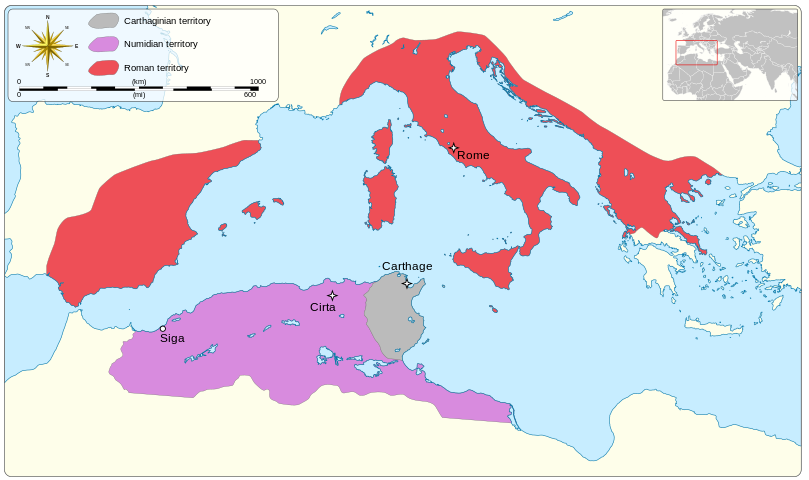

The Numidian king Masinissa, allied with Rome, exploited Carthage’s military restrictions by encroaching on its territories. In 151 BC, a desperate Carthage violated its treaty with Rome by launching a military campaign against Masinissa. This action provided Rome with the pretext to destroy its long-standing rival. In 149 BC, Rome declared war, landing a massive force at Utica in North Africa and beginning the siege of Carthage.

Carthage’s Initial Resistance

Despite initial efforts to negotiate with Rome, Carthage faced humiliating demands, including disarmament and relocation away from the coast. Reluctantly, the Carthaginians surrendered vast quantities of weapons, only for the Romans to demand the city’s complete destruction. This ultimatum galvanized the Carthaginians to resist rather than abandon their homeland.

Carthage, a city of approximately 700,000 inhabitants, prepared for war by freeing slaves to bolster its army and fortifying its defenses. The city’s formidable walls spanned over 35 kilometers (20 miles) and included a 9-meter-thick (30 feet) defensive wall equipped with barracks for 24,000 soldiers. Despite their resourcefulness, the Carthaginians faced a numerically superior Roman force of approximately 40,000–50,000 troops under consuls Manius Manilius and Lucius Censorinus.

Map showing the territories of Numidia, Carthage, and Rome around 150 BC.

Early Setbacks for Rome (149–148 BC)

The Roman siege began with frontal assaults on Carthage’s walls, but the defenders repelled these attacks with tenacity. Under Hasdrubal, a seasoned Carthaginian commander, the city’s defenders harassed Roman supply lines and inflicted significant losses. The Romans faced additional challenges, including disease in their poorly located camps and logistical difficulties.

Scipio Aemilianus reorganized Roman forces, enforced discipline, and tightened the siege, leading the final assault that captured Carthage.

Scipio Aemilianus, a middle-ranking officer at the time, emerged as a key figure during these early failures. Displaying exceptional leadership, he stabilized panicked Roman forces during critical moments, earning widespread admiration. Despite these efforts, Roman progress remained sluggish, prompting the appointment of new commanders. However, the situation did not improve until Scipio’s eventual elevation to supreme command in 147 BC.

Scipio Aemilianus Takes Command (147 BC)

Scipio’s rise to command marked a turning point in the siege. His appointment required waiving age restrictions, reflecting the public’s confidence in his abilities. Upon assuming command, Scipio instilled discipline within the Roman forces, dismissing poorly motivated troops and focusing on a more methodical siege strategy.

Recognizing the importance of cutting off Carthage’s supply lines, Scipio ordered the construction of a massive mole across the city’s harbor to block maritime access. The Carthaginians responded by digging a new channel to the sea and constructing a fleet of 50 triremes. In a dramatic naval engagement, the Carthaginians initially surprised the Romans but mismanaged their retreat, losing many ships. This naval setback weakened Carthage’s ability to sustain the siege.

Statue of Scipio Aemilianus

Carthage Under Siege

With Carthage now isolated by land and sea, Roman forces intensified their assault. The Romans constructed a large brick wall near the harbor, enabling their soldiers to fire down onto Carthaginian defenders at close range. The Carthaginians, under Hasdrubal’s leadership, resisted fiercely. However, internal divisions within Carthage, exacerbated by Hasdrubal’s increasingly authoritarian rule, weakened their defense. His public execution of Roman prisoners further hardened Roman resolve and alienated Carthaginian moderates.

The prolonged siege caused immense suffering within Carthage. Food shortages, disease, and the relentless pressure of Roman attacks devastated the population. Nevertheless, the defenders displayed extraordinary resilience, fighting for their survival with ingenuity and determination.

The Final Assault (146 BC)

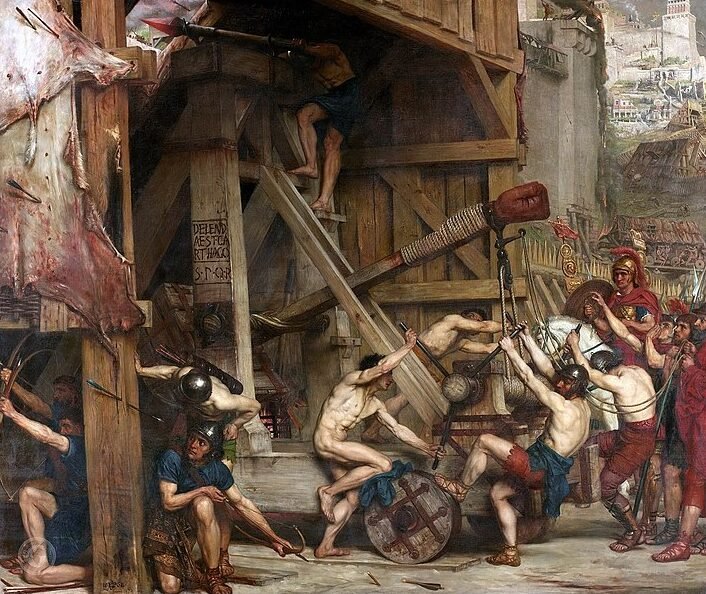

In early 146 BC, Scipio launched the final assault on Carthage. Roman forces breached the city’s outer defenses and systematically advanced through the urban landscape. Fighting was brutal and conducted street by street, with both sides suffering heavy casualties. The Romans used fire as a weapon, destroying entire districts and forcing the defenders into smaller, more concentrated areas.

Over six days, the Romans cleared the city, encountering fierce resistance at every turn. The last stand took place at the Temple of Eshmoun, where 900 Roman deserters and Carthaginian loyalists held out. When defeat became inevitable, the defenders set fire to the temple and perished inside. Hasdrubal, who had surrendered to Scipio earlier, watched helplessly as his wife cursed him, killed their children, and leaped into the flames.

Aftermath of the Siege

The destruction of Carthage was thorough and deliberate. The city’s population was either killed or enslaved, with 50,000 survivors sold into slavery. Scipio allowed his troops to plunder the ruins before Roman authorities ordered the city to be razed. Contrary to popular myths, the Romans did not sow the city with salt. Instead, they forbade its rebuilding, effectively erasing Carthage as a political entity.

While Rome emerged victorious, the cost of this triumph was immense, leaving a legacy of destruction and cultural erasure.

The formerly Carthaginian territories were annexed into the Roman Republic as the province of Africa, with Utica as its capital. This new province became a critical source of grain for Rome, solidifying its economic importance. Although Carthage was rebuilt as a Roman city a century later, its Punic identity was effectively extinguished.

Catapulta by English painter Edward Poynter depicts a Roman siege engine in operation during the siege of Carthage in the Third Punic War.

Primary Sources and Historical Interpretation

The siege is extensively documented by ancient historians, particularly Polybius and Appian. Polybius, a Greek historian who accompanied Scipio during the campaign, provides a detailed and generally balanced account of the events. Appian’s later narrative complements Polybius, offering additional insights into the war’s brutality.

Modern historians have debated the reliability of these sources but generally regard Polybius as credible. Archaeological evidence, including the remains of Carthage’s fortifications and artifacts from the siege, corroborates key aspects of these accounts.

Legacy and Historical Significance

The destruction of Carthage marked the end of the Punic Wars and the rise of Rome as the dominant power in the Mediterranean. It demonstrated Rome’s ruthless approach to warfare and its determination to eliminate any perceived threats to its hegemony. The siege also highlighted the resilience of the Carthaginian people, whose desperate resistance remains a testament to their courage.

Carthage’s fall had far-reaching consequences. The Roman Republic gained valuable territory and resources, while Carthage’s annihilation served as a warning to other states that might challenge Rome. However, the war’s genocidal nature and the complete eradication of Carthaginian culture have led some modern historians to describe it as one of history’s earliest examples of total war.

Frequently Asked Questions

Archaeological site in Carthage.

Why did the Romans attack Carthage?

Despite Carthage’s disarmament and compliance with Roman demands, Rome used Carthage’s unauthorized military action against Numidia as a pretext for war, seeking to eliminate it as a rival.

What challenges did the Romans face during the siege?

The Romans suffered setbacks due to strong Carthaginian defenses, supply issues, and effective counterattacks, which prolonged the campaign until Scipio Aemilianus assumed command.

How did the Carthaginians resist the siege?

Carthage raised a citizen army, rebuilt its fleet, and used innovative tactics, including a new harbor channel and sorties, but ultimately could not withstand the prolonged Roman assault.

What happened during the final assault in 146 BC?

The Romans systematically destroyed Carthage, killing most of its population, capturing 50,000 prisoners for slavery, and burning the city to the ground.

What were the immediate consequences of Carthage’s fall?

Carthaginian territories became the Roman province of Africa, with Utica as its capital, and Carthage’s site remained desolate for a century before being rebuilt by Rome.