Italian Painter and Architect Pirro Ligorio

Pirro Ligorio (c. 1512–1583) stands as a multifaceted figure of the Italian Renaissance, renowned for his contributions to painting, architecture, garden design, and antiquarian studies. Despite the scarcity of documentation surrounding his early years, Ligorio’s impactful career, particularly in Rome and Ferrara, showcases his diverse talents and enduring legacy.

Early Life and Move to Rome

Born around 1512 or 1513 in Naples, then under Spanish rule, Pirro Ligorio was the son of Achille and Gismunda Ligorio, who were believed to be part of the noble class in Seggio di Portanova, a district in Naples. Naples during Ligorio’s youth was a city grappling with political turmoil and economic hardship.

Seeking better prospects, Ligorio left Naples at approximately twenty years old, relocating to Rome—a burgeoning center for the arts under the significant patronage of the Vatican. This move marked the beginning of his illustrious career in a city teeming with artistic innovation and opportunity.

Image: As the Vatican’s Papal Architect under Popes Paul IV and Pius IV, Pirro Ligorio played a key role in ecclesiastical projects. Ligorio designed the famous fountains at Villa d’Este in Tivoli for Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este and served as the Ducal Antiquary in Ferrara.

Early Artistic Career in Rome

Upon his arrival in Rome, Ligorio commenced his artistic journey with modest endeavors, focusing on painting and decorating the façades of residences and palaces. This niche had recently become available following the flight of Polidoro da Caravaggio in 1527, allowing Ligorio to establish himself despite his limited formal training. His inaugural documented contract, dated May 12, 1542, involved decorating the loggia of the archbishop of Benevento’s palace.

He was selected for his expertise in the grotesque style—a decorative form characterized by intricate friezes, Roman historical narratives, and trophy motifs, popularized by Raphael and his contemporaries. This style became a hallmark of Ligorio’s early works, reflecting his ability to blend artistic finesse with classical themes.

Surviving Early Works and Artistic Contributions

While many of Ligorio’s initial paintings were lost or repainted within a century, several drawings from his early period have endured.

These surviving sketches often feature façade paintings, Roman characters, and Renaissance antiquities, and have been attributed to Ligorio based on their thematic alignment with his known oeuvre. These drawings are now part of esteemed collections worldwide, including a significant piece at the Art Institute of Chicago.

In the mid-sixteenth century, he secured a notable commission to assist in decorating the Oratory of San Giovanni Decollato in Rome.

Among his contributions was the fresco “The Dance of Salome,” created between 1544 and 1553. This work exemplifies his dedication to Raphaelesque and Manneristic styles and remains one of the few large-scale early works attributed to him.

Antiquarian Pursuits and Scholarly Contributions

During the 1540s, Ligorio immersed himself in the study of classical antiquity, dedicating substantial effort to understanding and preserving Roman artifacts.

This scholarly pursuit coincided with the pope’s excavation projects, which sometimes led to the inadvertent destruction of valuable relics. Ligorio’s dedication culminated in the 1553 publication of “Delle antichità di Roma,” a significant contribution to the knowledge of Roman antiquities.

Additionally, he produced several engravings of ancient artifacts and attempted to compile an encyclopedia of Roman and Greek antiquities, fragments of which are preserved in the Biblioteca Nazionale in Naples. Despite his scholarly achievements, Ligorio faced accusations of forgery; however, no substantial evidence was ever found to substantiate these claims.

Cartographical Achievements

Parallel to his antiquarian interests, Ligorio ventured into cartography between 1557 and 1563. Leveraging his expertise in antiquities and his artistic skills, he produced several detailed maps of Rome.

His most acclaimed cartographical work, “Antiquae urbis imago” (Image of Ancient Rome), published in 1561, is celebrated as a pinnacle of his mapping endeavors. This topographical map provided a comprehensive and detailed representation of ancient Rome, blending historical accuracy with artistic precision, and remains a testament to Ligorio’s versatility and intellectual breadth.

Appointment as Architect of the Vatican Palace

Ligorio’s career experienced a significant advancement when Pope Paul IV ascended to the papacy in 1555.

In 1558, seeking to appoint a fellow Neapolitan to a prominent architectural position, Paul IV appointed Ligorio as the Architetto Fabricae Palatinae, or Architect of the Vatican Palace.

Ligorio worked alongside his assistant, Sallustio Peruzzi, undertaking several key projects. His initial major project under Paul IV involved completing a chapel within the newly constructed Papal apartment. This task required him to design two large angel paintings, a project he successfully completed within approximately ten months.

Concurrently, he was commissioned to design a casino near the Belvedere Court for the pope. Although initially delayed due to financial constraints, this project would later become one of Ligorio’s cornerstone works under the patronage of Pope Pius IV.

Enhancing the Papal Palace and Monstrance Design

Under Paul IV’s directive to improve the Vatican Palace, Ligorio was entrusted with addressing the inadequate lighting in the Hall of Constantine. Collaborating closely with the pope, Ligorio orchestrated the demolition of the old papal apartment and the integration of a rooftop garden, thereby enhancing natural light within the hall.

Towards the end of Paul IV’s papacy, Ligorio was commissioned to design a monstrance (a type of tabernacle) for special papal journeys. Although Paul IV died before its completion, his successor, Pope Pius IV, valued the continuation of such projects and directed Ligorio to finalize the monstrance, which was subsequently gifted to the Duomo in Milan.

Major Works under Pope Pius IV

Pope Pius IV, who succeeded Paul IV in 1559, was a vigorous patron of the arts, particularly architecture. Differing from Paul IV, Pius IV prioritized the completion of existing projects over initiating new ones, a philosophy that aligned perfectly with Ligorio’s dedication to restoration and preservation of classical antiquities. Ligorio continued his collaboration with Sallustio Peruzzi, embarking on the remodeling of the Vatican Library in 1560. Financial limitations likely confined this project to smaller-scale enhancements involving woodworking and masonry.

A significant commission during Pius IV’s papacy was the continuation of the papal casino near the Belvedere Court. In May 1560, Ligorio was tasked with expanding the project to include a second story, a large fountain, and an oval courtyard with arched entryways. The decorative elements adhered to Ligorio’s favored Raphaelesque style, earning the casino the name Casino of Pius IV.

Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt lauded it as “the most beautiful afternoon retreat that modern architecture has created.” In recognition of his contributions, Ligorio was granted honorary Roman citizenship on December 2, 1560, a prestigious honor bestowed upon only three individuals in the sixteenth century: Michelangelo, Titian, and Fra Guglielmo della Porta. This accolade solidified Ligorio’s status and significantly increased his volume of commissions, marking Pope Pius IV’s reign as one of Ligorio’s most prolific periods.

Engineering and the Restoration of Acqua Vergine

During this period, Ligorio also made significant strides in engineering, particularly with the restoration of the Acqua Vergine, an ancient Roman aqueduct vital for supplying clean water to Rome. The aqueduct’s dysfunction had forced residents to rely on the unsanitary waters of the Tiber River.

The Italian architect spearheaded its reconstruction starting in April 1561, a project that spanned approximately five years. This endeavor underscored his commitment to both architectural beauty and functional engineering, ensuring that the city’s infrastructure met the needs of its inhabitants.

Contributions to the Belvedere Court

In the early 1560s, Ligorio contributed to the development of the Belvedere Court, focusing on the Nicchione initially designed by Bramante. The Italian aritst added a semicircular loggia, which became a popular site for Rome’s festivals and fireworks displays.

Additionally, he designed an open-air theater on the southern end of the Belvedere Court, completed in May 1565. Although this theater was later demolished in the eighteenth century, the Belvedere Court itself was notably used for a grand tournament in March 1565 to celebrate the marriage of the pope’s nephew. Ligorio’s design ensured that the Nicchione was viewable from a window in the pope’s apartment, effectively framing the space like a picturesque painting.

Organizing the Vatican Archives and the San Pietro Church

In 1565, Ligorio was entrusted with organizing the Vatican archives, designing a structure specifically for housing these records. This building deviated from his usual ornate Mannerist style, adopting a more utilitarian and modest design to reflect its functional purpose and Pope Pius IV’s preferences.

Following Michelangelo’s death, Ligorio was appointed as the architect of the San Pietro church in May 1564. This appointment incited animosity from Giorgio Vasari, a prominent Renaissance artist and Ligorio’s rival, who subsequently excluded him from his renowned “Vite,” a collection of biographies of prominent artists.

Ligorio collaborated with Giacomo Vignola on the San Pietro project, but their efforts yielded minimal progress, leading to their eventual dismissal under the new pope.

Imprisonment and Later Vatican Years

Ligorio’s tenure at the Vatican faced a brief interruption in the summer of 1565 when he was imprisoned for one week on allegations of fraud, specifically for allegedly stealing building materials from various papal projects. An extensive investigation led to the removal of his writings and the confiscation of medallions valued at six thousand scudi.

Although the punishment was relatively minor, these accusations further tarnished Ligorio’s reputation and compounded earlier suspicions of forgery.

With the ascent of Pope Pius V in 1566, Ligorio’s role at the Vatican diminished due to ideological differences between the two popes. Pius V relegated Ligorio to minor woodworking and design projects, allowing him to retain the title of Palace Architect until around June 1567. During the latter part of Pius V’s papacy, Ligorio returned to Ferrara to undertake work there.

Work in Ferrara and Villa d’Este

Ligorio had previously been engaged by Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este in September 1550, before his Vatican appointment. As the Cardinal governed Tivoli, Ligorio managed his antique collection and served as a key advisor. Tivoli’s abundance of ancient villas and temples provided Ligorio with ample opportunities to advance his research on Roman antiquities while the Cardinal enriched his personal collection.

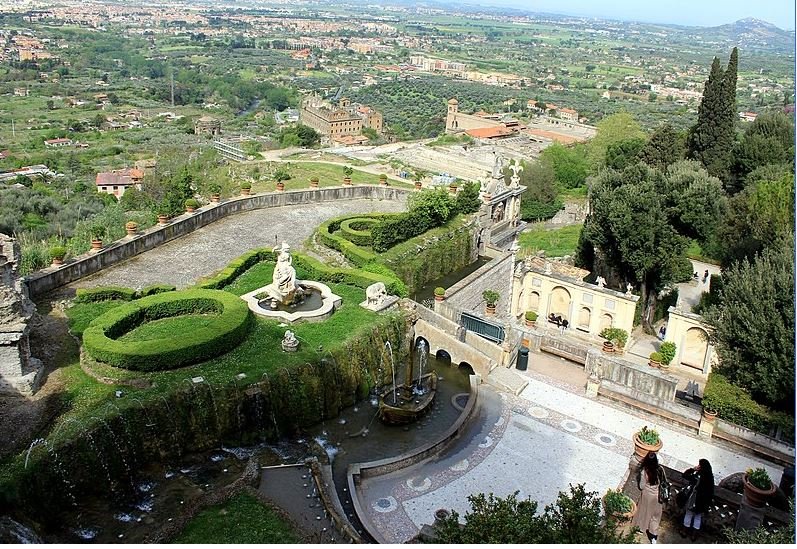

One of Ligorio’s most notable projects in Ferrara was the Villa d’Este in Tivoli. Initially, Ippolito II d’Este intended to convert an old monastery into a luxurious villa. Construction faced delays throughout the decade but resumed fully in 1560 under the main architect Giovanni Alberto Galvani.

Ligorio took charge of designing the villa’s extensive gardens, which featured intricate waterworks and fountains, leveraging his expertise in aqueduct engineering. He created both a large public garden and a more intimate private garden accessible directly from the palace. The private garden utilized shaded walls to provide a secluded retreat.

Themes in Villa d’Este Gardens

David Coffin, Ligorio’s prominent biographer, identifies three major themes in the Villa d’Este gardens: the interplay between nature and art, geographic representation, and mythological iconography. Ligorio seamlessly integrated natural elements like flora and fauna with artistic features such as sculptures and waterworks, reflecting Renaissance ideals. The fountains symbolized the three rivers feeding into the Fountain of Rome, honoring the Cardinal’s artistic appreciation.

Additionally, Ligorio incorporated mythological motifs inspired by the Garden of the Hesperides, particularly referencing Hercules’ trials, which echoed both ancient mythology and the Cardinal’s Christian values. This harmonious blend of nature, art, geography, and mythology exemplifies Ligorio’s imaginative prowess and his ability to create spaces that are both aesthetically pleasing and intellectually stimulating.

Service under Duke Alfonso II d’Este and Earthquake-Resistant Design

In December 1568, Ligorio returned to Ferrara to serve under Duke Alfonso II d’Este as the Ducal Antiquarian and Lector at the University of Ferrara. His responsibilities included preparing the ducal library and organizing an antique museum for the court. Ligorio contributed numerous drawings and designs, reinforcing his reputation as an antiquarian scholar. In 1580, he was honored with honorary citizenship, adding to his dual identity as a Neapolitan and Roman citizen.

The devastating earthquake in Ferrara on November 16, 1570, profoundly influenced Ligorio. He authored a treatise on historical earthquakes, detailing the effects of the Ferrara quake and proposing designs for earthquake-resistant structures. Diverging from the contemporary belief of earthquakes as supernatural events, Ligorio approached them as natural phenomena, advocating for architectural adaptations such as thicker brick walls and stone piers—principles that align with modern seismic engineering.

Legacy and Historical Recognition

Pirro Ligorio died in October 1583 following a severe fall in Ferrara. Despite his substantial contributions to Renaissance architecture, classical antiquity scholarship, and garden design, Ligorio remains a relatively obscure figure in historical accounts. The initial biography by Giovanni Baglioni in 1642, followed by subsequent biographies by Milizia and Nagler, contain numerous factual inaccuracies, likely stemming from the limited documentation of Ligorio’s life. The absence of records from his early years and the loss of many of his works further obscure his legacy.

In the twentieth century, historian David Coffin emerged as the foremost authority on Ligorio, authoring “Pirro Ligorio: The Renaissance Artist, Architect, and Antiquarian.” This comprehensive biography remains the most detailed and accurate account of Ligorio’s life and works, filling gaps left by earlier, less reliable sources. Coffin’s research has been instrumental in reconstructing Ligorio’s contributions and ensuring that his multifaceted genius is recognized within the broader narrative of Renaissance Italy.

Personality and Personal Traits

Coffin characterizes Ligorio’s personality through three primary traits: curiosity, imagination, and ambition. Ligorio’s insatiable curiosity drove him to explore diverse fields such as painting, garden design, engineering, cartography, and archaeology.

His imaginative prowess is vividly illustrated in the Villa d’Este gardens, where he harmoniously blended botany, sculpture, waterworks, and mythology.

Ligorio’s ambition propelled him to undertake numerous projects, earning both admirers and adversaries. His rivalry with Giorgio Vasari, who excluded him from “Vite,” significantly impacted the preservation and recognition of Ligorio’s legacy, as Vasari’s omission led to Ligorio being less documented compared to his contemporaries.

Major Architectural and Artistic Contributions

Throughout his career, Ligorio was responsible for several significant projects that exemplify his diverse talents:

- Grotesque Façades in Rome: His early work in decorating the façades of Roman residences and palaces established his reputation for mastery in the grotesque style, integrating classical motifs with intricate designs.

- The Dance of Salome Fresco: This large-scale fresco for the Oratory of San Giovanni Decollato remains one of his few surviving early works, showcasing his skill in blending Raphaelesque and Manneristic styles.

- Casino of Pius IV: Ligorio’s design for the papal casino near Belvedere Court, featuring a second story, large fountain, and oval courtyard, is celebrated as one of his masterpiece architectural endeavors, blending aesthetic beauty with functional design.

- Restoration of Acqua Vergine: His engineering prowess was evident in the restoration of Rome’s Acqua Vergine aqueduct, ensuring a reliable supply of clean water to the city and demonstrating his ability to integrate engineering solutions with architectural projects.

- Villa d’Este Gardens: Perhaps his most renowned work, the Villa d’Este gardens in Tivoli, reflect his genius in garden design. The gardens’ intricate waterworks, fountains, and harmonious integration of natural and artistic elements highlight his ability to create immersive and thematically rich environments.

- Belvedere Court Enhancements: His contributions to the Belvedere Court, including the Nicchione and the open-air theater, underscore his versatility in both architectural design and entertainment-oriented spaces.

- San Pietro Church Appointment: Although ultimately unsuccessful, Ligorio’s appointment as the architect of the San Pietro church following Michelangelo’s death illustrates his prominence within the Roman architectural scene, despite facing professional rivalries.

Image: The courtyard of the Casino of Pius IV

Frequently Asked Questions

When and where was Pirro Ligorio born?

Pirro Ligorio was born around 1512 or 1513 in Naples, Italy, which was under Spanish rule at the time.

What prompted Ligorio to move from Naples to Rome around the age of twenty?

The turmoil and poverty in Naples motivated him to seek better opportunities in the flourishing art community of Rome, heavily influenced by Vatican patronage.

What was Ligorio’s first recorded contract in Rome, and what style was he selected for?

His first recorded contract was on May 12, 1542, to decorate the loggia of the archbishop of Benevento’s palace. He was selected for his proficiency in the grotesque style.

Villa d’Este gardens showcase genius in design, waterworks, and harmony.

What is considered Ligorio’s most acclaimed cartographical work, and when was it published?

“Antiquae urbis imago” (Image of Ancient Rome), published in 1561, is considered his most acclaimed cartographical work.

Under which pope did Ligorio become the Architect of the Vatican Palace?

Under Pope Paul IV, Ligorio was appointed as the Architetto Fabricae Palatinae (Architect of the Vatican Palace). One of his initial major projects was completing a chapel in the newly constructed Papal apartment, including designing two large angel paintings.

What is Pirro Ligorio’s most notable contribution to garden design, and what themes did he incorporate?

His most notable contribution to garden design is the extensive gardens at Villa d’Este in Tivoli. He incorporated themes of the interplay between nature and art, geographic representation, and mythological iconography, blending flora, fauna, sculptures, and waterworks seamlessly.