The Tragic Life, Reign and Execution of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots

Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots, was born Mary Stuart (or Mary Stewart) on December 8, 1542, in Linlithgow, Scotland. Following the passing of her father, she became the queen of Scotland at only six days old. When she was 17 years old, the lovely Mary became the queen consort of France as a result of her marriage to King Francis II. After the death of Francis II, Mary returned home to claim her birthright as Queen of Scotland in 1542. A series of poor spousal and civil decisions forced Mary to give up the throne in 1567. She then fled to England to seek protection under her first cousin, Queen Elizabeth I.

Mary’s Catholic allegiance soon became a threat to England and the crown. To top it all off, she also gambled by making strong claims to the English throne. Eventually, she was put on trial for treason under the charges of seeking to overthrow Queen Elizabeth I. The Protestant-dominated court and counsel of Queen Elizabeth found her guilty of the charges and gruesomely executed her on February 8, 1587, in Northamptonshire, England.

Infancy and Early Years

When Mary was born (on December 8, 1542) her father, King James V, was on the throne. Her mother was Mary of Guise, a French-born from the powerful House of Guise. Mary of Guise was King James V’s second wife.

Sadly for Mary, King James V died six days after Mary’s birth. The king got ill after a horrific defeat at the hands of the English at Solway Moss. What this meant was that Mary was about to spend her formative years only raised by her mother. As she was a baby, her mother became the queen regent of Scotland. The queen regent thought it wise to let the young Mary spend her childhood in France. She also wanted to protect Mary from the aggressive moves of her Protestant half-brother, James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray.

Therefore at the age of five, Mary departed for France. The Roman Catholic King of France, King Henri II, took her in and raised her as his own. Her grandmother (Antoinette de Guise) and the entire House of Guise featured very strongly in young Mary’s life.

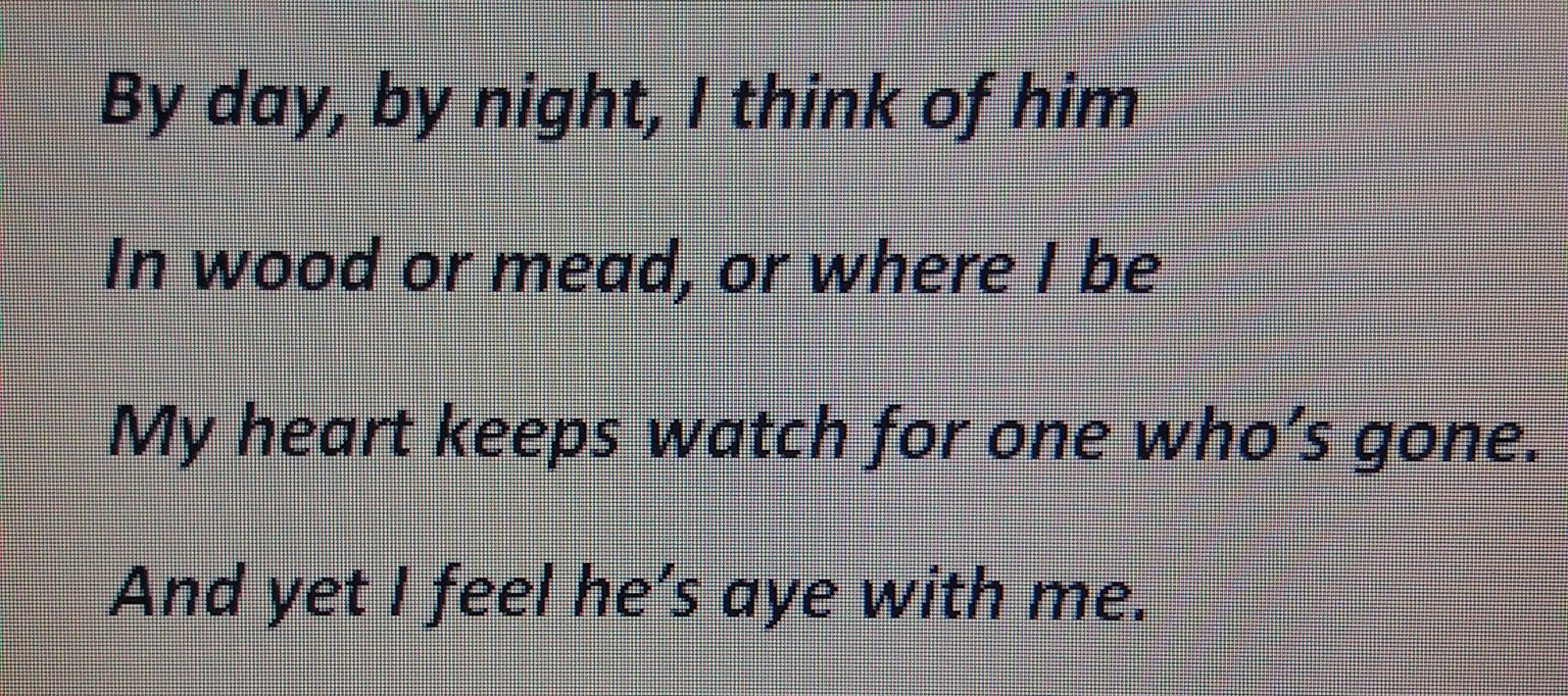

Mary grew up strong and beautiful. She was described as a kind, very smart and confident girl. Additionally, she proved very successful in most of her courtly training. She learned Latin, French, Spanish, Italian, and Greek. Music and poetry were one of her favorite subjects.

At about 5 feet 11 inches, Mary was considered reasonably tall for a woman in the 16th century. With her slightly golden-red hair, oval shaped face and amber-colored eyes, many French nobles and royal members took great interest in her. As time passed, Mary fully assimilated the French culture.

Her First Marriage

Mary and Francis in Catherine de’ Medici’s book of hours, c. 1558. From the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

King Henri II arranged a marriage between his eldest son, Francis, and Mary. Historians believe that the young Mary was head over heels for Francis. As it was typical back in those days, King Henri II’s only purpose of the marriage was to bring France and Scotland together. The two countries shared a common hatred for England and their Protestant religion. England and France had intermittently been warring with each other for years.

With Scotland and France both predominantly ruled by noble Catholics and lords, it seemed natural that the two would want to be drawn into a closer alliance. In April 1558, Mary and Francis happily got married in Notre-Dame Cathedral, Paris.

The English translated version of a French poem written by Mary about her husband Francis II of France

Prior to the marriage, there was a lot of resistance from England. Henry VIII of England had always wanted his grandniece, Mary, to marry his son, Prince Edward (later King Edward VI). There was even an arrangement between the regents in Scotland and Henry VIII. The marriage was intended to secure peace between Scotland and England.

However, Henry VIII’s erratic behavior and military advances into Scotland proved very destabilizing to this intended union. Also, the Roman Catholic lords in France and Scotland pulled out of this union partly because Henry VIII had angered them by separating England from the Catholic Church. The separation occurred because Henry VIII divorced his first wife, Catherine of Aragon.

More:

Mary Stuart’s Claim to the English Crown

Across the Channel, Mary’s cousin Elizabeth was crowned queen of England in 1558. Elizabeth I inherited the crown after brief reigns of Edward VI and Mary I. Elizabeth was Mary’s first cousin (twice removed). Technically speaking, Mary had a valid claim to the English throne as well. This is because Mary was the great niece of the deceased King Henry VIII. Furthermore, her grandmother, Margaret Tudor, was King Henry VIII’s sister.

In the eyes of the Roman Catholics in England, Mary was the rightful heiress to the throne of England. They felt that Mary had a greater birth right to the English crown than her cousin, Elizabeth. They argued that Henry VIII annulment of his marriage to Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn, meant that Elizabeth became an illegitimate heiress. Their claim was more of a political claim than a religious claim.

Furthermore, the Catholics in England greatly sympathized with the French. The French refused to let the sway they had under Elizabeth’s predecessor, Mary I of England, fade away. Most prominent among the people who wanted Mary to inherit the English throne was her father-in-law, King Henri II of France.

Brief Period as Queen Consort of France

In 1559, the court of King Henri II of France was plunged into mourning after King, Henri II died. Mary’s young husband, Francis, was crowned Francis II, King of France. This made Mary the new queen consort of France. Sadly, this position only lasted for a year or so. King Francis died in 1560. It is said that the young King Francis II died from an infection to the ear.

Her husband’s death devastated the 18-year old Mary. Six months prior to her husband’s death, Mary also mourned the passing of her mother, Mary of Guise, in June 1560. The dark period of Mary’s life was just about to start.

Return to Scotland and Reign

After a year of mourning the loss of her husband and mother, Mary returned to her home in Scotland in 1561. She was 18 at this time and fully ready to be crowned Queen of Scotland. After years of staying in France, she found it very difficult adapting to her new environment. Scotland had changed both politically and religiously.

The Protestants had made huge gains in Scotland. By virtue of their sympathy to fellow protestant Elizabeth I in England, some of them looked at Mary (a deeply Catholic person) with a lot of suspicion. The Calvinist reformer John Knox, a staunch protestant, was among those people that considered Mary as an outsider with a different religion. Elizabeth also rejected any claims Mary had on the English throne.

Mary’s first few years on the Scottish throne were relatively peaceful. She worked to ensure that there was some level of religious freedoms. There weren’t so many religious persecutions. Also, the nobles and Protestants did not give her much trouble. She, in turn, swayed to the side of religious tolerance and respect for the Protestants.

Also, she brought on board her half-brother, James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, into her counsel. She was very popular with the common folks because she delicately wrestled a bit of power from the nobles and strengthened her crown. Externally, she maintained very decent relationships with nations such as England, Spain, and France. Unfortunately, this period of relative peace came to an end when Mary re-married. Most of her counsel, including James Stewart, opposed her second marriage.

Read More: Major Accomplishments of Queen Elizabeth I of England

Second Marriage and the Dawn of Utter Chaos

Mary’s new groom was the Earl of Darnley, Henry Stewart (Stuart). Stewart was her maternal cousin. They got married in July 1565. Their marriage produced a son named James (later King James VI) on June 19, 1566. Many historians consider her union with Stuart the singular event that brought the chips down.

In the first place, Queen Elizabeth, her cousin, did not approve of the marriage. Elizabeth was aggrieved because Mary failed to consult her before the marriage.

Secondly, Mary’s noblemen were annoyed by her marriage. Her half-brother and counselor, James Stewart, was one of the people to switch sides and move away from Mary. The noble Scots considered Henry Stewart as an odd sickly man who was up to no good. It was alleged that he was also very power hungry. It was obvious that he wanted to position himself as joint ruler (like a crown matrimonial) of Scotland. These and many more other factors infuriated the Scottish nobles.

A year into her marriage, her opposition had drummed up the rumor that she was in an affair with James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell. They accused her of plotting the death of Darnley so that she could marry James Hepburn. It was also around this same period that Darnley tragically died in an explosion in his house. All fingers pointed at Mary, even though the accusers lacked any concrete evidence. A number of love letters and correspondences (magically) surfaced that implicated Mary in an extra-marital affair with James Hepburn.

Many historians consider those letters nothing but fictitious letters forged by her opponents to discredit her reign. There was an off chance that Mary and Darnley’s marriage crumbled, but not to the extent of plotting to kill Darnley. Regardless of this, the rumors kept flowing thick and fast. Soon, Mary’s reputation came to disrepute.

Regardless of the backlash, Mary proceeded to marry James Hepburn three months after her second husband’s death.

How Queen Mary’s reign in Scotland crumbled

Mary was forced to relinquish her royal seat in 1567.

In May 1567, Mary and James Hepburn got married at Holyrood. Mary’s unwise decision of marrying a prime suspect in the death of her second husband did not go down well with the noblemen and Lords in Scotland and England.

Some argue that she did not do so entirely out of passion but did so because she needed a man to assist her to steer the affairs of her kingdom. She needed a noble that could unite the various warring nobles. All she wanted was to stabilize the situation that was getting out of hand. Besides, Mary’s health had started to briefly deteriorate.

The chaos in her palace resulted in the banishment of Hepburn. Soon, Mary herself was put under house arrest at Loch Leven Castle. She was later forced to abdicate her throne in 1567. Her one-year-old son, James (James VI), became King of Scotland on July 24, 1567. James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, acted as regent during the minority of James.

After some few military losses to her opponents during the battle at Langside, Glasgow, Mary fled to England and sought protection under her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I. Mary and her son never met again.

She arrived in England in May 1568. The comfort that she was expecting in England never materialized. Instead, she was not welcomed gracefully in England. This was out of fear of her claim to the English throne. For the next two decades or so, Mary spent most of her time moving from one place to another, unofficially as a prisoner of England.

Imprisonment in England

Queen Elizabeth strategically put Mary in places far from the Scottish border, but also far from the British hub of power. There was simply too much suspicion around Mary. Did she really kill her husband? Was she in England to depose her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I? Would her presence in England stir up a Catholic uprising in England? All of these questions must have gone through the mind of Elizabeth.

Additionally, Mary’s bad health issues resurfaced. She was miles away from her home and constantly got accused of murdering her own husband. Time in England was anything but good for her.

The Catholics in England secretly hoped that Mary could assert her claim to the English throne. Some of them tried to convince Elizabeth to name Mary as heiress. Therefore, the English Protestants saw Mary’s continued presence on their soil as a genuine threat to the Protestant Queen and Protestantism in general. Investigations into her correspondence while in England revealed that Mary may have communicated with Anthony Babington, a man who was involved in a failed plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth.

Read More: The Deadly Feud Between Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots

The execution of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots

Copy of Mary’s effigy, National Museum of Scotland | Image: Wikipedia.org

Under the passive blessing of Queen Elizabeth I, the Protestant lords and earls set out to prosecute Mary under the charges of murder and treason. In Mary’s defense, she protested the entire trial. She argued that she was not a subject of Queen Elizabeth I, and therefore could not be tried in England.

Her prosecutors also brought a series of evidence in the form of her supposed love letters (also known as the Casket Letters) with second husband Hepburn as proof of her infidelity and murder. In the course of her trial, Mary was moved from one castle to another. Perhaps the essence of doing this was to prevent her from plotting her escape.

On October 16, 1586, Mary was found guilty at the trial held at Fotheringhay under the charges of plotting to kill Elizabeth. She was sentenced to death on February 7, 1587. She appeared very calm and composed all throughout the proceeding.

Her country folks put up no resistance; neither did her son James VI of Scotland come to her defense. The tides in Scotland had shifted from a predominantly Catholic ruling class to one that was Protestant. James only officially protested against his mother’s captivity. But that was all. He refused antagonizing Elizabeth and the Protestants in England for fear that he could jeopardize his claim to the English crown.

On February 8, 1587, at the age of 44, Mary was beheaded at Fortheringay Castle, Northamptonshire, England. Through the course of the trial, as well as the sentencing, Queen Elizabeth decided to remain indifferent so as to save face in Scotland.

In 1612, her son, King James I (then King of England and Scotland) laid Mary remains at Westminster Abbey.

Queen Mary’s Motivations and Legacy

Mary was never once considered weak. She lived in a time that saw national religions and allegiances shift very swiftly. She may have lacked the political acumen to rule and bring men in line, something her cousin, Elizabeth did so perfectly well. But who could blame her? She lost her dad at such an early age. Her first husband died when she was young. The odds were stuck against her right from childhood. Catholicism was simply on the decline in England and Scotland, and Mary was a Catholic.

Perhaps she could be described as a victim of her circumstances in the sense that male chauvinists in both England and Scotland did not wish her well ever since she occupied the Scottish throne.

On the other hand, she truly had a hand in her own undoing. She made some very terrible decisions. Disregarding the rumors and going ahead with the marriage to Hepburn. Certainly, such moves only added more fuel to the raging fire in her life. Had she lived in an earlier age in the future, Mary’s wits and openness to religious freedoms would have augured well for her. Sadly, she lived in a time and an environment that made it difficult for her to circumvent the ill fortunes that came storming her way.

Mary Stuart (December 8, 1542 – February 8, 1587)

Commonly asked Questions and answers about Mary Stuart

We’ve compiled the following key questions and their corresponding answers to summarize Mary Stuart’s life story:

How is she related to the English monarchy?

Mary was the great-niece of Henry VIII of England and the cousin of Elizabeth I. She had a claim to the English throne and was considered by many Catholics as the legitimate queen of England, especially after the death of Mary I of England.

Why was Mary Stuart’s early life spent in France?

Due to the political situation in Scotland and concerns about her safety, Mary was sent to France at the age of five to be raised at the French court. She also entered into a marriage alliance with the French dauphin, Francis, strengthening the bond between Scotland and France.

What led to her abdication?

She faced numerous political challenges during her reign in Scotland, including religious conflicts, personal scandals, and issues of governance. Her marriage to Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, was particularly tumultuous, and his murder led to public outrage. These events, combined with pressure from rebellious Scottish lords, led to her abdication in favor of her son, James VI, in 1567.

What happened after her abdication?

Mary sought protection from her cousin, Elizabeth I of England. However, given Mary’s claim to the English throne and her Catholic faith, she was seen as a threat. Elizabeth had her imprisoned for nearly 19 years.

Why was Mary executed?

Mary became implicated in several plots to assassinate Elizabeth and place herself on the English throne. The most notable of these was the Babington Plot. As a result of her involvement, she was tried and found guilty of treason, leading to her execution on February 8, 1587.

Who succeeded Mary as the ruler of Scotland?

Her son, James VI of Scotland, succeeded her. He later became James I of England, uniting the crowns of Scotland and England upon the death of Elizabeth I.

What is Mary’s legacy?

Her life has been the subject of numerous plays, novels, and films. She is often portrayed as a tragic figure, caught between political and religious intrigues. Her legacy is multifaceted, with some seeing her as a martyr for her faith and others as a flawed monarch.

Where is Mary Stuart buried?

Initially, Mary was buried in Peterborough Cathedral. However, in 1612, her son James VI and I had her remains exhumed and reinterred in Westminster Abbey in a chapel opposite Elizabeth I.

How is she related to the current British monarchy?

She is a direct ancestor of the current British monarch. She was the great-great-grandmother of King James II of England (James VII of Scotland), and the line of succession continues through to the present day, with Queen Elizabeth II being a direct descendant.