Mexican War of Independence: Causes, Major Battles, & Outcome

For many centuries, Spain rule Mexico with absolute control. Mexico (formerly the Viceroyalty of New Spain) was Spain’s most cherished and biggest colony in the Americas. Father Hidalgo was a bold leader who inspired tens of thousands of economically and socially marginalized people in New Spain to fight for independence from Spain.

The Mexican Independence Day is the biggest holiday for most Mexicans. Every September 16 there is a celebration of freedom all across Mexico and across the world, in places that host people of Mexican descent. Those celebrations usually feature a gigantic fiesta of fireworks, family parties, great food and wine and colorful parades. And then there are the million bells ringing through Mexico City on the night, reminiscent of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla famous “Grito de Delores.” But these are the happy times.

The early 19th century journey to Mexico’s independence from Spanish rule was one made with sweat and blood. However, there was a stubbornness that drove the revolutionaries whose willpower did not bend even while staring death in the face. The Mexican War of Independence was made of a series of revolts that arose from years of political tensions in Mexico and Spain.

Contrary to popular view, new studies have shown that the events that led to the formation of the nation of Mexico were not only created by the elites. Urban popular groups and rural communities were essential parts of the nation building process which transformed Mexico into an independent country and ensured equality of the Spaniards and Creoles.

When did the Mexican War of Independence begin?

Mexicans celebrate Mexican Independence Day on September 16 in honor of the day, September 16, 1810, when Father Hidalgo issued the “El Grito de Dolores” battle cry. That day is generally agreed as the day the Mexican War of Independence began.

Background to Mexican War of Independence

The Mexican War of Independence spanned the period between September 16, 1810 and September 27, 1821. It was a series of armed conflicts between the people of Mexico and their Spanish colonial government. Simply put, it was Mexico’s reaction against Spanish authoritarianism. Note that the Mexican War of Independence is not the same as the Mexican Revolution. First of all, these 2 conflicts are 100 years apart from each other and their major difference lies in their purpose.

The Mexican War of Independence was meant to separate Mexico from Spain in order for Mexico to become independent. However, the Mexican Revolution, which started on November 20, 1910, was a rebellion against the elitist policies of Porfirio Diaz, a dictator president who had been in power for over three decades.

Factors that led to the Mexican War of Independence

With regard to the Mexican War of Independence, internal conflicts was the main factor that galvanized Mexicans to fight for an independent nation, a nation free of Spanish control. These factors have been discussed below.

· The Conquest of New Spain

The fight for Mexican independence can be traced back to the 16th century when the Spaniards eyed the American mainland as a source of natural resources, such as gold and land.

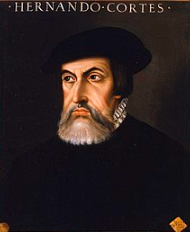

In 1521, Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés and about 450 men allied with the indigenous tribes to overthrow the Aztec empire. At its height, this conquest birthed three hundred years of Spanish rule in Mexico (then New Spain).

The Native American population did not only have to contend with the aggressive nature of Spanish conquistador, but their population was also decimated by smallpox, which was introduced to their world by the Europeans. Image: Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortes

Over time, many Mexicans became frustrated by the social structure in the colony. Racial injustice was rampant, economic conditions had declined, and many of the policies were skewed in favor of the Spaniards.

There was also disrupted trade and famine that resulted from periods of drought at the time. A call for change was imminent.

· The Enlightenment Philosophy

Central to the fight for the Mexican independence was the role 18th century Enlightenment philosophers such as John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau played in shaping the thinking of many countries in Latin America. These thinkers promoted the ideals of liberty, constitutional government and tolerance, and eschewed absolute monarchy. The people of Haiti embraced this philosophy and deposed their French colonial rule to become an autonomous Latin American country. By so doing, they paved the way for other colonies in the region to fight for independence, including Mexico.

· The Caste System

The social status in colonial Mexico was based on a caste system. The caste system was a social hierarchy by which one’s worth was determined. The determining factors included wealth, inherited rank, background, and skin color. This system caused a lot of discontent and divisions regarding the abuse of rights.

At the top of the hierarchy were the Spanish-born citizens or peninsulares who held control over the government and most of the money. They enjoyed the greatest social privileges and legal protection. The next tier included the creoles or criollos, i.e. the American-born Spaniards, who enjoyed almost the same privileges as the peninsulares. However, they could only be appointed to lower level government jobs. Under them were the mestizos, people with mixed European and Indian ancestry. These group had very little say in the government. At the bottom of the hierarchy were people of African ancestry, some with European or Indian heritage (mulattos).

Apart from the Spanish-born citizens, members from all the other groups often complained of being discriminated against. As a reaction, they took part in the attempt to topple the Spanish colonial powers. Unlike many revolutionaries in which hate for the sitting government was rampant, this revolt was borne not out of hate but of necessity.

· Napoleon’s Invasion of Spain

When Napoleon invaded Spain in 1808, it weakened Spain’s hold on its colonies and gave rise to a series of uprisings throughout country. Napoleon had pressured King Ferdinand VII of Spain (the son of Charles IV) to cede the crown. Thereafter, Napoleon placed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as the new king of Spain and by extension, the ruler of Mexico.

While the Spanish bureaucrats acknowledged Joseph’s kingship, the people of Spain detested him. This development led to the Peninsula War (from 1807 to 1814) in the Iberian Peninsula, as Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom and the then French Empire locked horns. During this 7-year war, Spain was pushed to a precarious position.

Inspired by the American and French Revolutions, the Mexicans who craved Independence saw an opportunity to make a similar bid like Haiti’s and seek a sovereignty that will protect the interests of its people.

Read More: 5 Major Events that Led to the American Revolution

Conspiracies & Insurrections

The Enlightenment ideology was embraced mostly by the Creoles who expressed anger at the monarchy’s seeming favoritism of the peninsulares. The Creoles also felt that their privileges within the caste system were being decreased by the Spanish authorities. The Creoles’ dissatisfaction culminated in several full-fledged conspiracies and insurrections to depose the monarchy. Most notable among these were the Valladolid Conspiracy and the Querétaro Conspiracy.

· The Conspiracy of Valladolid

This conspiracy took place in the city of Valladolid (now Morelia). Taking shape in 1809, the conspirators included military personnel, the elite, lawyers and others. The leader of this conspiracy movement was José Maria Obeso, the Infantry Lieutenant of the Valladolid Regiment.

At the time, Spain had governed Mexico for over three centuries, and the political terrain was riddled with strife. Coupled with the Napoleon invasion came dissensions between the peninsulares and the creoles over matters bordering on the setting up of a junta.

The junta was supposed to be a political committee which would control the government on behalf of the Spanish monarch after a plot to depose Ferdinand VII succeeds. Although colonial authorities thwarted the conspiracy in December 1809, it became a breeding ground for more insurrections.

· The Querétaro Conspiracy

Similar to the Valladolid conspiracy, this conspiracy was engineered by some significant creoles in the city of Querétaro who wanted to establish a junta and ultimately an autonomous Mexican state. The conspirators often met under the pretext of being members of the Literary and Social Club of Querétaro. They also set up units in nearby cities.

The members of the Querétaro Conspiracy comprised people from all walks of life, including the Corregidor of Querétaro, Miguel Dominguez Alemán and his wife, Josefa Ortiz de Dominguez, military officers Ignacio Allende and Ignacio Aldama and most importantly, the parish priest of Dolores, Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla.

Hidalgo was recruited mainly because of his important relationship with high-ranking individuals in and around New Spain. The conspiracy was scheduled to be executed in December, 1810, but three months before the date, it was discovered by the Spanish authorities.

When Allende and Aldama received news about the arrest of their co-conspirator, Josefa Ortiz de Dominguez, they went to Dolores to meet with Hidalgo in order discuss their next plan of action.

Afraid of being arrested, Allende suggested they flee Mexico and go into hiding, but Hidalgo encouraged that they stay to fight for the interest of the Mexican people. Finally, an agreement was reached: the rebellion would hold, even sooner than had been previously planned.

This decision laid the foundation for the revolt began by Hidalgo, which in turn led to the Mexican War of Independence.

“El Grito de Dolores” – Hidalgo’s famous battle cry

Father Miguel Hidalgo proclaim the national independence in Dolores.

In the early morning hours of September 16, 1810, Hidalgo ordered the ringing of the Dolores parish bells to summon the inhabitants of the town. Thereafter, he passionately issued the “Grito de Dolores” (Cry of Delores) which was a call for the people to take up arms and fight against the Spanish colonial government for Mexico’s autonomy and general good.

Hidalgo’s exact words in the “Grito de Dolores” have been widely debated among scholars. However, they generally agree that Mexican independence fighter appealed to the ideals of independence, an end to slavery, and the return of native lands to their original landowners. English speakers have attempted to translate the message as follows:

Long live religion. Long live our Blessed Mother of Guadalupe. Long live Ferdinard VII. Long live America and death to bad government.

Although Hidalgo’s speech launched the 11-year struggle for independence, the revolt was driven by other key players, including military officers Ignacio Allenda and Vincent Guerrero (who later became Mexico’s president) and fellow Catholic priests José María y Pavón and Mariano Matamoros.

These revolutionaries led populist armies of over 90,000 farmers, creoles, nobility in Spanish America and members of the Catholic Church within the colony. Normally, these group of people would hardly belong in the same clique. Be that as it may, their unlikely alliance grew out of a shared vision of freedom.

The Hidalgo Revolt

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla was the first leading figure to call for Mexico’s independence. The Catholic priest issued his famous battle cry on September 16, 1810.

Chanting “Independence and death to bad government”, Hildago, with a banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe in hand, led the very large but poorly equipped insurgent army through the capital. Many more Indians and mestizos joined them as they marched toward Mexico City.

· Siege of Guanajuato on September 28, 1810

Siege of the Alhondiga de Granaditas, Guanajuato, 28 September 1810

The rebels came up against their first serious opposition when they got to Guanajuato, a prosperous city for the peninsulares. Hidalgo’s army swelled as they were joined by my numerous miners from the city. The insurgent army besieged the granary where Spanish forces of about 400 men were gathered. After a long, ferocious battle, more than 2,000 Indians and 500 Spaniards were killed. The larger army size of the insurgents was the only reason for their win against the Spanish forces.

The rebels proceeded to take over the city and began a looting spree throughout Guanajuato. They raided homes of both creoles and Spaniards. The siege caused a rift between Hidalgo and Allende. The latter was disgusted at the men’s pillaging of the homes. He wanted the fight to be more “noble.” Hidalgo, on the other hand, felt that many of the insurgents would withdraw from the fight without the looting rampage. He further clarified that most of the peasants had joined the revolt primarily to loot and to kill the Spaniards.

When news of the violence at Guanajuato spread throughout the colony, the Spanish authorities in Mexico City set about organizing a more tactical army of as a defense.

The Battle of Monte de Las Cruces

Battle of Monte de las Cruces

The Battle of Monte de Las Cruces is believed to be one of the most pivotal battles of the Mexican War of Independence. It started at eight in the morning of October 30, 1810. The battle ground lay between Mexico City and Toluca. Though the fight began with more than 90,000 rebels, almost 2,000 of them lost their lives by the end of the bloody proceeding. This was largely due to their inferior weapons and lack of tactical training. In spite of those challenges, that insurgents showed immense courage in the face of a major European power and defeated them in the end.

As the revolutionaries began to make their way to Mexico City, Hidalgo suddenly insisted on retreating to the north although his army was in a good position to invade and attack Mexico City. Against the advice of Allende, Hidalgo turned back and headed for the Guadalajara metropolis, intending to make a stop at Toluco. One the way, many of the insurgents withdrew from the march. The army was left with only 40,000 men upon arrival at Toluco.

The Spanish Royalist army, which had laid an ambush for the revolutionaries in Guadalajara, noticed the drastic decline in the number of Hidalgo’s men. They saw an opportunity to strike and grabbed it. They attacked the insurgent army with their relatively advanced weapons.

With the odds stack against them, Hidalgo and Allende made a choice to escape with the rest of their men. The Royalist forces led by General Félix María Calleja trailed their foes to the Calderón River.

The Battle of the Calderón River

Upon reaching the Bridge of Calderón on January 16, the revolutionaries took a defensive stand as they prepared to face off their opponents. They were determined to defend the Calderón Bridge, which was seen as an important opening into Guadalajara, their intended destination. At this point, the insurgent army comprised over 80,000 poorly-armed men, while the Royalists totaled only about 7,000 but were armed with better guns and ammunition.

As the battle waged on, the insurgents seemed to be winning mostly as a result of their numerical superiority. Then out of the blue, a Spanish grenade exploded, destroying much of the rebels’ ammunition and causing utter chaos. The explosion also caused the rebel forces to spread over the area. Some rebels fled the battlefield in terror and were chased after by Royalist troops.

The Battle of the Calderon River finally ended with a decisive defeat of the insurgent army.

Capture & Execution of Hidalgo

Following their defeat at Calderón River and subsequent escape, Hildago and the rest of his men were ambushed near the wells of Bajan in Coahuila as they were trying get into the United States.

Shortly after their arrest, Allende, Jimenez and Aldama were tried and found guilty of treason. They were executed on June 26. A few weeks later, Hidalgo was defrocked and excommunicated by the Church. Eventually on July 30, 1811, he suffered the same fate as his fellow independent heroes: execution and decapitation. Hidalgo’s body was conveyed to Mexico City for its final burial.

Today, the remains of the all four revolutionaries rest in the column of the Angel of Independence in the center of the city.

Insurgency under José María Morelos (1811-1815)

José María Morelos succeeded Father Hidalgo as the leader of the rebels.

Following the execution of Hidalgo, Morelos assumed the leadership of the fight for independence and controlled the political and military aspects of the struggle.

By the end of August 1811, Morelos’ rebel forces had taken over a huge portion of the southern coast of Mexico. In June 1813, he called for a national conference of representatives from all of the provinces.

The meeting was held at Chilpancingo (present-day Guerrero) to discuss matters concerning the future of Mexico as a sovereign nation. Among the major points documented in what became known as Acta Solemne de la Declaración de Independencia de la América Septentrional (Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America) were Mexico’s independence, universal male suffrage, enshrining of Roman Catholicism as the sole official religion, abolition of slavery, and equality before the law.

Execution of Morelos

In spite of the initial successes by Morelos’s troops, internal conflicts led to the collapse the movement. The colonial authorities broke the siege of Mexico City after 6 months and took control of the surrounding areas.

In November, 1815, Morelos was captured and taken to Mexico City. He was tried by a Spanish court which convicted him of heresy and treason. Sentenced to death, Morelos was executed by a firing squad on December 22, 1815.

Morelos was best known for building an excellent and well-structured military force. He is credited with injecting a sense of discipline into the revolutionary forces. He was not bloodthirsty like many revolutionary figures were known to. Rather, he resisted using senseless violence as a war instrument. Morelos’ most remarkable achievements during his leadership were the conquests of the Oaxaca province and defense of the city of Cuautla.

Insurgency under Vicente Guerrero (1815 -1820)

Vicente Guerrero

After Morelos’ death, Guerrero held the reins as the new leader of the insurgents and has been described by some historians as the most important of all the leaders. His journey to national hero status started during his travels as a muleteer around Mexico, where he got familiar with the growing independence movement. It was during one of these journeys that he had the pleasure of meeting Morelos. The young revolutionary went on to launch his military career and later distinguished himself in battles in cities such as Izúcar and Taxco.

As the commander-in-chief of the insurgent army, Guerrero’s allied with generals Guadalupe Victoria and Isidora Montes de Oca in the independence struggle. His reputation as a powerful leader soared with every victory. Once, the viceroy Apodaca had tried to commission him to offer his service to New Spain but the gallant soldier refused.

The Plan of Iguala & Independence

Over time, Guerrero lost most of his men in battles and was defeated by the Spanish forces. However, all the years of fierce battles had started to take a toll on the Spaniards. As a result, the commander of the Spanish forces, General Agustin de Itubide decided to call a truce with Guerrero.

With the famous “Abrazo de Acatempan” (The Acatempan Hug,) a peace agreement was sealed in the city of Acatempan, bringing an end to the over a decade-long civil war.

In February, 1821, Guerrero succeeded in convincing Iturbide to join the fight for Mexico’s independence. The two joined forces and formed the Trigarante Army (the Army of the Three Guarantees) under the Plan of Iguala.

Per the terms of this proclamation, Roman Catholicism would be supreme over all others, Mexico would have full Independence, and there would be social equity among “new” Mexico’s ethnic groups. All attempts by the Spanish viceroy to nullify the Mexican independence and sovereignty proved futile.

The Santa Maria-Calatrava Treaty

After more failed attempts to recapture Mexico, Spain eventually recognized Mexico’s independence on December 28, 1836 by the signing of the Santa Maria- Calatrava Treaty (also known as the Definitive Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Mexico and Spain this agreement). The name of the Treaty was coined from the last names of the signees; Mexican Commissioner Miguel Santa Maria and Spanish state minister José Maria Calatrava.

It’s been estimated that the 11-year Mexican War of Independence claimed the lives of up to half a million people.

Independent Mexico

Agustin de Iturbide became emperor of the First Mexican Empire in September 1821. Image: Flag of the Mexican Empire.

Post-independent Mexico was first governed as an empire with its first emperor being Iturbide in 1822. After ruling for less than a year, Mexico’s economy began failing as it received no further assistance from Spain. The then-governor of Veracruz, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, as a way of resolving Mexico’s economic crisis, declared Mexico a Republic and overthrew Iturbide with the help of other generals in March 1823.

After Iturbide’s deposition, Mexico was ruled by a Supreme Executive Council whose key members included Guerrero.

In 1824, Guadalupe Victoria was proclaimed the first president of Mexico under a new constitution. Four years later, on April 1, 1829, Guerrero was elected as the second president of the Mexican Republic.

As president, Guerrero succeeded in creating reforms for the working class, abolishing slavery, and made sure that the rights of every race was respected. Clearly, his government was people-oriented and sought to bring about an economic turnaround for a population, which was mostly poor after years of oppression and bloodshed.

Significance of Mexico’s Independence

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo signed in 1848 between the United States and Mexico was an effect of the Mexican War of Independence and eventual independence. The treaty officially ended the Mexican-American War and resulted in Mexico ceding about 55% of its territory to the United States. These territories included present-day California, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming.

After Mexico’s emergence as an independent state, many Mexicans around the world migrated back home to start a life on their terms. Mexicans who were living in the United States also had the opportunity to go back home or become U.S. citizens. The U.S. government guaranteed the protection of their property rights even if they chose to relocate.

As a result of War of Independence, early stages of Mexico’s independence were marked by economic stagnation that continued until the 1870s. Foreign investors were too afraid to invest in a country with a colorful history of political instability.

However, with birth of the Republic came the hope of economic modernization and progress. During the Porfirio presidency (1896-1911) for example, Mexico witnessed tremendous economic growth. And when President José de la Cruz instituted the rule of law, it ushered in some bit of political stability and a vibrant economy, which in turn allowed the country to receive high capital investment to fund national projects.

Today, the rate of rural banditry has decreased, transportation and communication facilities have been advanced.

Did you know?

- As of 2022, Mexico is the third largest country in North America with an area of almost 2 million square kilometers.

- One of the world’s largest pyramids, the Great Pyramid of Cholula, is located in Mexico. Standing at 66 meters tall and about 400 meters wide, it is way bigger than Egypt’s Pyramid of Giza!

- Mexico does not have an official language. Though there are about 68 known languages in Mexico, the majority of the citizens speak Spanish.

- The country is home to beautiful beaches, great cuisine and ancient ruins.