African Art: History, Characteristics, Famous Works, & Major Facts

African art encompasses the vast and diverse artistic expressions of the African continent, stretching from ancient rock paintings in the Sahara to contemporary installations in major cities. Its history is as old as humanity itself, and its evolution reflects the continent’s rich cultural, social, and political heritage.

One could define African art as representing African culture, identity, and spirituality, a self-conscious portrayal of African-derived beauty standards.

In the article below, World History Edu takes an in-depth look at the history, including some of its major characteristics and famous works:

Ancient Roots

African art has ancient origins, with some of the earliest known artworks being the rock paintings and engravings from sites like the Sahara Desert and Southern Africa.

These paintings, which date back thousands of years, depict animals, humans, and abstract designs, providing insights into the spiritual and daily lives of ancient African societies.

Male head; 550–50 BC; terracotta; Brooklyn Museum (New York City, USA). The head’s mouth is slightly ajar, possibly indicating an intent to speak, as if the figure wishes to convey a message. It appears as though the figure is caught mid-discussion. The eyes and eyebrows exude a sense of inner peace and tranquility.

Material Diversity

African art is not limited to one medium. For millennia, artists have used everything from wood, bronze, and ivory to beads, leather, clay, and cloth.

The choice of material often has cultural and religious significance. For example, in many West African societies, wood is believed to have spiritual properties, making it a preferred material for religious sculptures.

Masks and Masquerades

One of the most recognized forms of African art is the mask. Used in religious and social ceremonies, masks are more than decorative objects; and in many African communities, it was believed that those masks were vehicles through which spirits can be contacted or through which stories and morals can be conveyed. The wearer embodies the spirit of the mask, transforming during the performance.

Mbangu mask; wood, pigment & fibres; height: 27 cm; by Pende people; Royal Museum for Central Africa. The mask, with its hooded V-shaped eyes and distinct artistic elements such as facial contours, warped features, and contrasting colors, symbolizes a troubled individual, capturing the essence of internal strife.

Sculpture

Sculptural art forms a significant part of African artistic tradition. These range from ancestral figures, fertility dolls, and reliquary guardians to royal regalia and intricate bronzes.

Notable are the Nok terracottas of Nigeria and the Benin bronzes, which display a high degree of sophistication and craftsmanship.

Benin plaque with warriors and attendants (16th-17th century)

Textile Arts

African textile art is vast and varied. The kente cloth of the Akan people of Ghana, the mudcloth (bògòlanfini) of the Bamana people in Mali, and the Akwete cloth of the Igbo are just a few examples. These textiles are not just functional but carry symbolic meanings, often associated with status, occasion, or regional identity.

Kente cloth, the traditional or national cloth of Ghana, is predominantly worn by the Akan people in Southern Ghana

Beadwork

Beadwork is another significant aspect of African art, with beads used to create both functional and decorative items, including jewelry, crowns, and garments. The Maasai of East Africa, for instance, are renowned for their intricate beadwork, which has both aesthetic and cultural significance.

Art as Functional

A lot of African art is functional. Pottery, textiles, and tools are often adorned with patterns and designs, making them both utilitarian and artistic. This integration underscores the importance of art in daily and ritual life.

Influence of Colonialism on African Art

The colonial period had a profound impact on African art. European collectors and museums were interested in African art primarily as ethnographic objects rather than artistic creations. The “primitive” label often attached to African art during this period influenced modernist European artists searching for new inspirations, like Picasso and Matisse, who drew from African art’s abstraction, form, and geometry.

Post-Colonial and Contemporary Era

Post-independence, African art began to reflect the complexities, challenges, and aspirations of new nation-states. Contemporary African artists, like El Anatsui, Yinka Shonibare, Ben Enwonwu, and Njideka Akunyili Crosby, engage with global themes, melding traditional techniques and motifs with new mediums and ideas.

Fulani Girl of Rupp (1949) by Nigerian artist Ben Enwonwu

Pan-African Festivals

Events such as the FESTAC ’77 (Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture) held in Nigeria highlighted the richness of African culture and art, showcasing the diversity and unity of African artistic expression, and fostering a sense of Pan-African identity.

Art and Identity

African art has often been a medium to assert identity, whether tribal, national, or continental. It has played a role in resistance against colonialism, in nation-building, and in the Pan-African movement.

Maiden spirit mask; early 20th century; wood & pigment; Brooklyn Museum (New York City, USA)

Global Recognition

Today, African art is gaining increasing recognition on the global stage. Auctions, exhibitions, and museums around the world are giving African art its deserved spotlight, acknowledging its influence on global art trends and its intrinsic value.

Ngady-Mwash mask; 19th century; Ethnological Museum of Berlin (Germany). Like many other Kuba masks, this one is decorated with cowrie shells. Like many Kuba types of masks, ngady-mwash mask is extensively polychromed, or multicolored and often decorated with cowrie shells.

Influence of religion on African art

Traditional African religions deeply influence the continent’s art. Much of African art revolves around religious symbolism, functionalism, and utilitarianism, with many creations intended for spiritual purposes.

Ancestors, considered intermediaries between the living and divine, are central, and art often acts as a conduit to ancestral spirits. While art might depict gods, its functional value is also emphasized. Notably, Christianity and Islam’s arrival has interwoven their traditions with African art and beliefs.

African art often features the human figure representing the living, dead, chiefs, dancers, trades, or even gods. Additionally, a recurring theme is the fusion of human and animal forms, highlighting the continent’s rich symbolism and spiritual beliefs. Image: Plank mask (emangungu); possibly early 1900s; wood; by Bembe people; Cleveland Museum of Art (USA)

Art Markets and Fairs

The growth of art markets and fairs in cities like Lagos, Marrakech, and Cape Town indicates the burgeoning interest in African art both within the continent and internationally. These platforms provide opportunities for artists to showcase their work and for collectors and enthusiasts to engage with African art in its diverse forms.

Anthropomorphic pot; early 20th century; pottery; 40.0 × 24.0 cm (153⁄4 × 91⁄2 in.); by Mangbetu people; Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

Integration with Technology

Contemporary African artists are integrating technology into their work, using digital media, photography, and installations to comment on themes like urbanization, globalization, and digital culture in the African context.

Kente Clothes from the Akan Culture

Kente cloth, deeply rooted in Akan culture, is said to be inspired by spider webs, as weavers aimed to replicate their intricate patterns. Renowned globally for its vibrant colors and designs, Kente was originally a representation of royal prestige and dominance. Today, while it remains a symbol of tradition in its native context, its influence has spread, with various cultures embracing and adapting its significance.

Akan goldweights

Akan goldweights, known as mrammou, are brass weights used by West Africa’s Akan people for measuring in trade. Ownership of a full weight set indicated a man’s status. Newlyweds often received small sets, enabling the groom to join merchant trade with respect.

Beyond their utilitarian role, these weights, in their miniature forms, encapsulate West African culture. They depict various elements like adinkra symbols, flora, fauna, and human figures, making them not just tools but also artistic representations of Akan life and values.

Benin artworks stolen during British colonial rule

Benin art originates from the Kingdom of Benin, a pre-colonial African empire in today’s South-South Nigeria. The renowned Benin Bronzes comprise over a thousand metal plaques and sculptures that once adorned the royal palace.

Created from the 13th century by the Edo people, the collection includes brass and bronze sculptures, portrait heads, and smaller artifacts. In 1897, during the Benin Expedition, a British force seized most of these artworks.

Two hundred pieces went to the British Museum, while European museums acquired the remainder. Today, many reside in the British Museum and prominent German and American institutions.

Plaque equestrian an Oba on horseback with attendants; between 1550 and 1680; brass; height: 49.5 cm (197⁄16 in.), width: 41.9 (161⁄2 in.), diameter: 11.4 cm (41⁄2 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

Traditional African art

Traditional African art encompasses the iconic forms often showcased in museum collections. These pieces represent historical and cultural practices and are revered for their authenticity, craftsmanship, and significance. As the most studied forms, they offer insights into the diverse cultures, beliefs, and histories of African societies, serving as both artistic and anthropological treasures.

African traditional masks

Wooden masks are prevalent in West African art, representing humans, animals, or mythical beings. Traditionally, they play crucial roles in rituals, including celebrations, initiations, and war preparations. A chosen dancer, donning the mask, enters a trance to connect with ancestors. Masks can be worn in three styles: directly over the face, as helmets, or as crests atop the head.

Kifwebe mask; wood; Royal Museum for Central Africa (Tervuren, Belgium)

Often embodying spirits, it’s believed ancestral spirits possess the mask wearer. Typically crafted from wood, these masks may be adorned with ivory, animal hair, plant fibers, pigments, stones, and semi-precious gems.

Frequently Asked Questions

Warrior ancestor figure; 19th century; wood; 84.1 × 26 × 23.2 cm (33.1 × 10.2 × 9.1 in.); by Hemba people; Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth, Texas, USA)

What exactly is African art?

Africa, humanity’s cradle, boasts ancient art forms spanning a myriad of styles, from abstract to naturalistic. This vast continent, comprising 54 distinct countries as of 2023, offers a rich tapestry of visual cultures, each resonating with its own unique artistic voice.

However, the broad term ‘African art’ often inadvertently diminishes this diversity, serving as a generic umbrella for the entire continent’s artistic output.

This headrest presents 19th century Luba Kingdom hairstyles; Musée du quai Branly (Paris).

Although occasionally many of us resort to this generalization, it’s essential to acknowledge that it glosses over the nuances of aesthetics, style, and genre intrinsic to each region.

Take, for instance, the stark contrast between the Bini’s art, renowned for the Benin Bronzes, and the Delta region’s art; both hail from Nigeria yet are worlds apart in artistic representation. Or the vast difference we see in the artworks from northern ethnic groups in Ghana such as the Mamprusi and Dagomba versus the works produced by southern tribes like the Ewe, Akan, and Ga-Adangbe. For example, Akan gold weights, made between 1400-1900, are miniature metal sculptures. Some symbolize proverbs, introducing a unique narrative aspect to African sculpture. Additionally, royal attire featured intricate gold sculptural elements, showcasing the artistry and significance of these weights in Akan culture.

The Ashanti trophy head, circa 1870, made of pure gold and weighing 1.5 kg, is housed in London’s Wallace Collection. Symbolizing a defeated enemy chief, it adorned the Asante king’s state sword.

Must one be Black to produce African art?

Furthermore, the term “African art” raises contentious questions about identity: Must one be Black to craft African art? In essence, while ‘African art’ provides a convenient categorization, it often oversimplifies the continent’s intricate and varied artistic landscape.

Just how broad is African art?

Traditional African art, often labeled as ‘tribal’ or ‘primitive’, is popularly associated with masks and sculptures due to their extensive collection by Europeans. These masks, deeply embedded in rituals like births, deaths, and weddings, may also carry political or religious weight.

Headdress; early 1900s; wood, antelope skin, basketry, cane, metal; by Ejagham people; Cleveland Museum of Art (USA)

However, Africa’s artistic expanse is vast, spanning functional items like pots, textiles, and jewelry, and personal clothes and adornments. It’s safe to say that African art in essence is not merely decorative or functional; it’s intertwined with the daily lives of people.

And unlike pre-20th-century European Art, which prioritized aesthetics and classical forms, traditional African Art is symbolic, emphasizing human interrelations. It can also be interpreted as an attempt to unveil the invisible parts of people’s lives, their shared values and aspirations.

Modern Makonde carving in ebony

How important is the human body in African Art?

Traditional African Art places significant emphasis on the human form, often bestowing figures with human attributes to enhance relatability. The human body in African culture goes beyond just representing beauty, it represents the collective spirituality of the people as well as life’s principles.

What role do animal elements play in African art?

Occasionally, we find many African artists integrate animal elements into their works. The question that begs to be answered is: What role do those elements play? One possible reason is that those elements are meant to represent ancestral or personal spirits, crafting hybrid beings.

Mask; early 20th century; wood, raffia & color pigments; by Yaka people; Rietberg Museum (Zürich, Switzerland)

What’s the deal with the serious posture of many African sculptures?

You’ll rarely, if ever, spot a reclining, screaming, or grinning figure in African art. The predominant posture is upright, emanating composure, dignity, and self-respect.

Mask for Obalufon II; circa 1300 AD; copper; height: 29.2 cm; discovered at Ife; Ife Museum of Antiquities (Ife, Nigeria)

Are precision and symmetry valued in African art?

Contrary to what some few Western art critics might say, African artists truly revere precision, valuing symmetry and balance. There are a plethora of African artworks that can boast of having no crude lines or imbalanced angles – a trait surprisingly shared with Western art ideals.

What does youth symbolize in African art?

Youth is celebrated, symbolizing vitality, fertility, and vigor. The sculptures often possess a radiant “youthful glow,” achieved by intensive polishing, resulting in almost reflective surfaces.

Such luminosity isn’t merely aesthetic; rough or uneven surfaces were deemed unattractive and even morally questionable, especially when representing spiritual entities. In the past, it was widely believed that the masks and other artworks were living entities with superhuman powers.

Female figure for a small temple; 20th century; Indianapolis Museum of Art

What are some of the oldest African artworks?

Ancient rock art in Botswana’s caves, dating back 30,000 years, showcases the daily life and rituals of the San people, a hunter-gatherer community. These paintings, portraying humans, hunting scenes, and animals, serve as historical records.

Why should African art be more inclusive?

In recent years, the scope of African art has expanded to embrace all African cultures and their historical visual contributions. Beyond just traditional sculpture and masks from non-Islamic regions of West, Central, and Southern Africa, there’s a growing emphasis on artworks from the 19th and 20th centuries.

This inclusive approach offers a richer understanding of Africa’s diverse visual aesthetics. Additionally, art from the African diaspora in Brazil, the Caribbean, and the southeastern US is now also being integrated into the study of African art.

What is the meaning of contemporary African art?

The term “contemporary” generally refers to current artists, but in the context of African art, it encompasses a broad range of mediums like metalwork, portraiture, sculpture, tapestries, and installations.

These artists often challenge Eurocentrism, globalization, and other themes, merging traditional art forms with modern techniques and tools. This blend has produced strikingly innovative works.

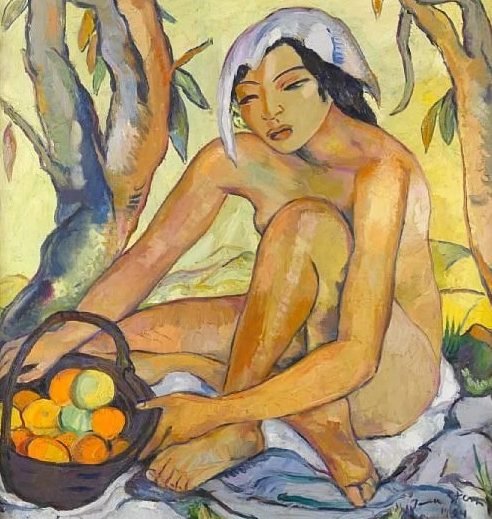

Notable among them are South Africans artists William Kentridge and Irma Stern; Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui; Egyptian-born artist Fathi Hassan; Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu; and Nigerian artists Ben Enwonwu and Marcellina Akpojotor.

“Seated Nude with Oranges” (1934) by Irma Stern

Who are some of the most prominent contemporary African artists?

Ben Enwonwu and Marlene Dumas are two African artists I greatly admire. While my preferences are personal, I’ve curated a list of ten prominent contemporary African artists who have significantly impacted the global art scene. The artists, listed without any specific ranking, consistently exhibit innovation and creativity within their respective genres. Their unique approaches not only represent the diversity and richness of African artistry but also challenge and redefine the global art narrative, ensuring that African voices and perspectives are recognized and celebrated.

What are some of the most expensive African artworks?

There is no doubt whatsoever that African art, both traditional and contemporary, is gaining traction in major global art markets like New York, London, Paris, and Johannesburg. Yet, even as prices for African art rise, they remain modest compared to European art. A notable example is Nigerian artist Ben Enwonwu’s masterpiece, “Tutu”, which sold for $1.68 million in 2018; it’s often likened to the Mona Lisa in its significance.

Another Nigerian artist, Akunyili Crosby, has made waves, with three of her pieces each selling for over $3 million between 2017 and 2018. Sotheby’s regards her as “the most valuable Nigerian artist ever and one of the most valuable female artists of all time.”

In 2005, Dumas’s painting “The Teacher” (1987) sold for a whopping $3 million at Christie’s London. Then in 2013, Ethiopian visual artist Julie Mehretu’s for $4.6 million at Christie’s New York.

However, when the above works are juxtaposed with the works of artists like Jeff Koons, whose works fetch prices over $80 million, there’s a stark contrast in the perceived value.

“The Teacher” (1987) by South African artist Marlene Dumas

What are some examples of art fairs and shows that promote African art?

Art fairs and shows have played a pivotal role in amplifying the voices of African artists and showcasing the diversity and dynamism of African art. Here are some notable art fairs and shows dedicated to promoting African art:

- 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair: Launched in 2013 in London, 1:54 is the leading international art fair dedicated to contemporary African art. Its name references the 54 countries that make up the African continent. The fair has expanded to New York and Marrakech.

- ART X Lagos: Established in 2016, ART X Lagos is West Africa’s premier international art fair, designed to showcase the best and most innovative contemporary art from the African continent and its diaspora.

- AKAA (Also Known As Africa): Located in Paris, AKAA is a fair dedicated to contemporary art and design from Africa. It’s a platform for dialogue and exploration, spotlighting the multifaceted creativity of the continent.

- Joburg Art Fair: Founded in 2008, the FNB Joburg Art Fair is one of the foremost art shows on the continent, showcasing African contemporary art, with a special focus on the South African art scene.

- Cape Town Art Fair: This fair has grown significantly since its inception and features work from leading African galleries and artists. It offers a comprehensive view of the African art landscape.

- LATITUDES Art Fair: Based in Johannesburg, LATITUDES emphasizes the rich artistic heritage of the African continent, putting the spotlight on established and emerging artists alike.

- Investec Cape Town Art Fair: This event showcases a diversity of work that represents the forefront of contemporary art from Africa to the world and the world to Cape Town.

- Dak’Art – Biennale de l’Art Africain Contemporain: Held in Dakar, Senegal, Dak’Art is one of the most significant contemporary art events in Africa. Established in 1992, it primarily focuses on promoting African contemporary art and artists.

- ART AFRICA Miami Arts Fair: Situated in the heart of Miami, this fair showcases works from emerging and established artists from Africa and its diaspora, emphasizing the cultural and artistic contributions of the African continent and Black artists.

- Addis Foto Fest: Founded by acclaimed Ethiopian photographer Aida Muluneh, this festival, based in Addis Ababa, highlights the best of contemporary African photography.

These fairs and shows, among others, have not only been pivotal in presenting African art to the global audience but have also provided a platform for dialogues, collaborations, and explorations that continually redefine the understanding of art from the continent.

Contributions made by African art

African art history holds a paramount place in the tapestry of global culture and heritage. Universally acknowledged as the birthplace of humanity, Africa’s artistic legacy offers a window into the earliest epochs of human civilization.

This history is not just sparsely chronicled in written records but is embedded in tangible artifacts and ancient landscapes. Millennia-old rock art scattered across the continent captures the essence of early human experiences, beliefs, and rituals

In a testament to Africa’s rich history and age-old artisanship, archaeologists unearthed shell beads in South Africa’s southernmost caves, crafted into necklaces over 75,000 years ago. These discoveries not only underscore Africa’s intrinsic role in the annals of world art history but also highlight the continent’s timeless contributions to human expression, craftsmanship, and civilization.

Why didn’t African art receive the merit and attention it deserves?

Understanding the depth and breadth of African art history is challenged by various factors. Primarily, limited archaeological excavations have restricted comprehensive insights into the ancientness of African art. Moreover, many art objects, crafted from perishable materials, have deteriorated over time, erasing countless artifacts from the historical record.

In many indigenous African communities, art wasn’t merely an aesthetic pursuit; it was functional. Once the intended purpose of an artifact was served, preservation wasn’t a priority. This transient approach to material culture meant that many art pieces, deemed invaluable post-function, were lost to time.

The period from 1840 onwards marked the onset of foreign colonization in sub-Saharan Africa, bringing with it profound shifts in values and perceptions. This era witnessed a significant outflux of African art, as travelers, merchants, and missionaries collected them out of curiosity. These pieces left their native land, often without proper documentation or understanding of their significance.

Colonialism further intensified this disconnect. The colonizers, with their Eurocentric perspectives, frequently failed to recognize the merit of indigenous art forms. As a result, the rich tapestry of African art history was neither adequately preserved nor documented.

This Eurocentric oversight has resulted in significant gaps in understanding the full spectrum of Africa’s artistic legacy. Now, as we delve into the history and seek to appreciate African art, we must reckon with these missing pieces and strive to give African art its rightful place in the global art narrative.

Mulwalwa mask; 19th or early 20th century; painted wood and raffia; Ethnological Museum of Berlin.

A re-examination of the very essence of African art

The burgeoning interest in African art, encompassing both tribal and contemporary forms, has instigated a profound introspection among scholars, investors, and institutions regarding its essence.

Previously relegated to the obscure corners of museum storage, many collections are now being showcased prominently in galleries, museums, and auction houses, celebrating their intrinsic beauty and significance in the global art narrative.

This renaissance has prompted both European and African researchers to delve deeper into these collections. Their aim is twofold: firstly, to enrich our understanding of African art history, and secondly, to potentially revive lost traditions and craftsmanship inherent to the cultures from which these artworks originated.

This renewed focus underscores the global recognition of African art’s pivotal role in the broader tapestry of art history and its capacity to provide invaluable insights into Africa’s rich cultural legacy.

Is Africa home to the oldest artworks in human history?

Africa, acknowledged as the cradle of Homo Sapiens, logically boasts some of the world’s most ancient and abundant rock art. Tracing the journey of early humans through these artworks provides a visual documentation of our shared ancestral past.

The Apollo 11 caves in Namibia house some of the oldest scientifically dated images, estimated to be between 24,000 and 27,000 years old. However, given the continent’s early habitation, many experts believe that some African rock art could be over 50,000 years old, making them some of the earliest expressions of human creativity and symbolic thought.

Beyond these, the Saharan sands of Niger preserve an even older testament to early artistic endeavors. Here, petroglyphs dating back to around 6500 BC depict animals, such as giraffes, hinting at past ecosystems, since such creatures no longer inhabit that region. These artworks not only offer insights into the artistic capabilities of our forebears but also provide invaluable clues to the landscapes, fauna, and climates of ancient Africa. The rich tapestry of rock art across the continent stands as a testament to Africa’s foundational role in the story of human evolution and artistic expression.

The issue of preservation over the centuries

Ancient rock art provides a window into the perspectives of early tribes and cultures, revealing how they perceived and interpreted their surroundings.

These visual records offer a glimpse into their spiritual beliefs, societal structures, and daily experiences, serving as a silent testimony to their cognitive and imaginative capabilities.

Kuba n’dop, king Mishe miShyaang maMbul (18th century)

They bridge the temporal divide, allowing contemporary observers an intimate connection to our ancestors’ worldviews.

However, this invaluable link to our past is under threat. Natural erosion, compounded by the encroachment of urban development, is deteriorating these ancient canvases.

Additionally, thoughtless acts of graffiti further mar these sites. Without preservation efforts, we risk losing these irreplaceable insights into humanity’s shared history.

The earliest known African sculptures

The annals of African art history house some of the world’s most ancient and intriguing artworks. Among the earliest are the terracotta sculptures from the Nok culture of Nigeria, dating between 500 BC and 200 AD. These fragmented figurines, mostly of heads, are crafted from grog and iron-rich clay. Their existence outside their natural settings showcases the long-standing tradition of abstract figural representation in Africa for over two millennia.

In the southern hemisphere, the Lydenburg heads hold a special place. Discovered in South Africa’s Lydenburg district, these fired earthenware figures are estimated to date back to 500 AD, making them the most ancient artworks found south of the equator. The civilization behind these seven heads remains largely enigmatic, but the deliberate and reverent manner of their burial suggests they held profound significance to their creators. The pronounced rings around the neck of these sculptures might indicate affluence and authority, but their precise meaning remains speculative, framed by our broader understanding of African art traditions.

Terracotta works also emerge prominently from regions like Jenne in Mali and Ife in Nigeria, dating between 1000 and 1300 AD. This tradition of creating impactful terracotta sculptures persisted through the 19th and 20th centuries, attesting to the material’s enduring appeal and significance in African artistic practices.

Additionally, the African continent boasts remarkable stone sculptures, with examples from the Kongo people and the Sherbro of Sierra Leone that can be traced back to the 16th century or earlier. Ivory, a precious material, was another medium that found favor among African artisans. Benin, in particular, witnessed exemplary ivory carvings in the same era, exemplifying the high degree of craftsmanship.

In essence, African art history is a rich tapestry of various materials and techniques spanning thousands of years. The continuity and change in materials, styles, and themes provide profound insights into the continent’s diverse cultures, beliefs, and social structures. Through these artifacts, we not only appreciate the aesthetic brilliance of ancient African societies but also gain an understanding of their values, aspirations, and worldviews.

Cast metal African artworks

Metal casting, especially using bronze, holds a significant place in the timeline of African art history. This robust art form is notable, primarily because it can withstand the termites that are rampant across the continent. The bronze casting tradition dates back to the 9th century AD and is credited to the Igbo-Ukwu tribe of Nigeria. Archaeological expeditions to their sites have uncovered intricate cast bronze regalia and other artistic masterpieces.

Nok male figure; 500 BC-500 AD; terracotta; from northern Nigeria; Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth, Texas, USA)

This ancient casting tradition reached its zenith with the Ife people of Yoruba, Nigeria. By the 12th century, the Ife began producing impeccable brass and bronze castings, continuing this art form until the 15th century. The life-size heads, masks, and smaller statues they crafted showcased exceptional realism. These pieces emanated a profound intensity, which is today, a hallmark of traditional African sculpture. Notably, they sometimes chose to cast in pure copper, a medium far more technically demanding than brass.

Nok seated figure; 5th century BC – 5th century AD; terracotta; 38 cm (1 ft. 3 in.); Musée du quai Branly (Paris)

By the 15th century, and continuing into modern times, the Yoruba people, especially in Benin, began crafting what are popularly termed ‘Benin bronzes’. Despite the name, these sculptures were mostly crafted from brass. This brass was sourced from traded vessels and ornaments, which were subsequently melted down to serve the artists’ purposes. Many of these sculptures were created for royalty and were believed to possess magical powers. They mirrored the prevailing sociopolitical structures, often dominated by divine Kings or Ife. The artworks, in essence, were a reflection of the communities’ deeply entrenched beliefs and values.

Interestingly, the 15th century also marked the arrival of the Portuguese in Africa. Their presence inspired Benin’s artists to start producing brass plaques with intricately carved reliefs. These plaques were fastened to the wooden beams of the royal palaces, serving both decorative and symbolic purposes.

Bronze Head from Ife

Aside from casting, African art history is punctuated with other artistic manifestations, offering chronological insights into its evolving nature. The most ancient textile fragments can be traced back to Igbo-Ukwu from the 9th century AD. Meanwhile, the Tellam caves in Mali shelter cotton and woolen fabrics, impeccably preserved since the 11th century.

A noteworthy mention is the Akan people of Ghana, who, in the 18th century, began creating miniature copper and bronze gold weights. These weights, often less than 5cm in height, were fashioned into a variety of forms – from animals and humans to fruits and abstract geometric designs. What set these diminutive sculptures apart was their vivacity and spontaneity, qualities not always associated with African sculpture.

To sum up, African art history, especially in the context of metal casting, is a rich tapestry of traditions, techniques, and timelines. From the ancient bronze artifacts of the Igbo-Ukwu to the brass plaques of Benin and the miniatures of the Akan, each era and ethnic group has added its unique chapter to this intricate story. Through their art, they not only showcased their exceptional craftsmanship but also provided a window into their beliefs, values, and societal structures.

Bobo Mask (Nyanga) from Burkina Faso, made in the early 19th century. Brooklyn Museum

Western scholars and artists who got inspired by African art

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, during and post-colonization, Westerners often labeled African art as “primitive,” a term laden with undertones of underdevelopment and impoverishment. This colonial mindset framed African art as technically deficient, associating it with socio-economic backwardness.

However, as the 20th century dawned, art historians such as Carl Einstein, Michał Sobeski, and Leo Frobenius began to redefine African art, recognizing its aesthetic value beyond just ethnographic significance. Concurrently, renowned artists like Paul Gauguin, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, André Derain, Henri Matisse, Joseph Csaky, and Amedeo Modigliani started drawing inspiration from African art, elevating its global appreciation.

“Les Demoiselles D’avignon” (1907) by Pablo Picasso

At a time when avant-garde artists felt limited by replicating reality, African art showcased the might of well-structured forms derived not just from sight but also imagination, emotion, and spiritual experiences. These forms resonated with artists, revealing a fusion of structural perfection and compelling expressiveness.

Early 20th-century artists, inspired by African art, became intrigued by abstraction and the reconfiguration of forms. They ventured into untapped emotional and psychological terrains previously uncharted in Western art. This transition transformed visual art’s role. No longer merely an aesthetic pursuit, it became a platform for philosophical and intellectual discourse, deepening its aesthetic essence.

African statues, crafted from wood or ivory, frequently feature inlays of cowrie shells, metal studs, and nails. Decorative clothing, a significant aspect of African art, showcases intricate designs. Ghana’s vibrant, strip-woven Kente cloth is one of Africa’s most intricate textiles, while the distinctively patterned mudcloth is another celebrated technique.

Ironically, Westerners view African abstraction as mimicking European artists like Picasso, Modigliani, and Matisse, who were deeply influenced by African art in the early 20th century. This cross-cultural inspiration was pivotal for Western modernism, exemplified by Picasso’s transformative work, “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907).

Bronze Head of Queen Idia; early 16th century; bronze; Ethnological Museum of Berlin (Germany). Four cast bronze heads of the queen are known and are currently in the collections of the British Museum, the World Museum (Liverpool), the Nigerian National Museum (Lagos) and the Ethnological Museum of Berlin

READ ALSO: The time when Picasso was suspected of stealing the Mona Lisa

Efforts to return African artworks from European museums back to Africa

Efforts to repatriate African artworks from European museums to their places of origin have been ongoing for years and have gained momentum recently. Historically, many of these artworks were taken during the colonial era under dubious circumstances, including looting, trades under duress, and straightforward theft. The argument for repatriation centers on moral, legal, and cultural grounds.

Proponents argue that returning these artifacts would be an act of justice, correcting historical wrongs and acknowledging the painful legacies of colonialism. Furthermore, these artworks hold immense cultural and spiritual significance for their countries of origin, and their return could play a pivotal role in national healing and cultural rejuvenation.

Two Bambara Chiwara c. late 19th early 20th centuries, Art Institute of Chicago. Female (left) and male Vertical styles

In recent years, some European institutions have initiated dialogues with African nations about potential returns. Notably, a 2018 report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron recommended the return of African treasures held in French museums. While some items have been repatriated, many remain in European collections, making this a continuing point of debate and negotiation.

Mwazulu Diyabanza, a Congolese activist, has confronted European museums, advocating for the return of African artifacts. He believes these items were wrongfully taken and should be repatriated to their rightful origins. Diyabanza’s direct actions highlight the ongoing debate about colonial-era artifacts housed in Western museums.

Figure of a horn blower; 1504–1550; copper alloy; Brooklyn Museum (New York City).

Similarly, the likes of Erna Brodber, a Jamaican writer and social scientist, and Yinka Shonibare, a British-Nigerian artist, have been vocal about returning African artifacts. Shonibare uses his platform and artworks to challenge the Western museum’s holding of African artifacts.

Also, Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) has been at the forefront of the dialogue for the return of stolen artifacts, particularly the Benin Bronzes.

Queen Mother Pendant Mask- Iyoba MET

Interesting facts

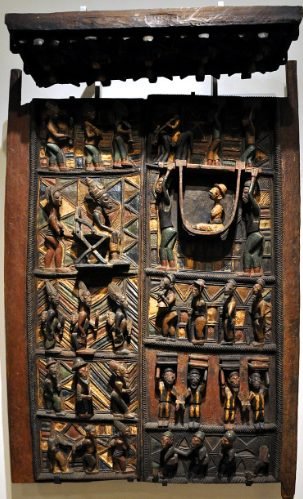

Pair of door panels and a lintel; circa 1910–1914; by Olowe of Ise; (British Museum, London)

- African art’s roots predate recorded history. The earliest known African beads, crafted from Nassarius shells and used as personal adornments, date back 72,000 years.

- In Africa, complex paint-making evidence dates back about 100,000 years, and pigment use can be traced to approximately 320,000 years ago.

- Sub-Saharan Africa, ancient Egyptian artworks, and indigenous southern crafts are pivotal contributors to African art. While often drawing inspiration from the rich natural surroundings, this art typically offers abstract representations of animals, plants, and natural patterns and designs.

- In West Africa, the oldest sculptures originate from the Nok culture of modern Nigeria, flourishing between 1,500 BC and 500 AD. These sculptures are characterized by elongated bodies and distinct angular forms crafted primarily from clay.

- In sub-Saharan Africa, around the 10th century, art techniques grew more intricate. Noteworthy advancements include Igbo Ukwu’s bronze craftsmanship and Ile Ife’s terracotta and metalworks. Bronze and brass castings, often adorned with ivory and gems, gained prestige in West Africa. Such works, like the Benin Bronzes, were sometimes exclusive to court artisans, symbolizing royalty and esteemed lineage.

- African economies, especially Nigeria and South Africa, are expanding. Nigeria’s growth is fueled by oil, attracting foreign investment and housing many of Africa’s millionaires. South Africa, with its established art ecosystem, is capitalizing on the rising interest in African art.

- Sotheby’s reveals that a significant percentage of contemporary African art buyers are from Africa itself. Africans, like collector Dr. Prince Yemisi Shyllon, have always cherished African art, emphasizing its preservation for legacy over mere investment. This poses a question: Should Western museums acquire African art for their collections?