History and major facts about the tomb of Tutankhamun

The discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922 by Howard Carter and George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, marked a watershed moment in the history of Egyptology and captured the imagination of the world.

This event not only shed light on previously unknown aspects of Ancient Egyptian life and culture but also sparked a global interest in Egypt’s ancient history.

The tomb, located in the Valley of the Kings across the Nile from Luxor, Egypt, contained the young pharaoh Tutankhamun, who reigned during the 18th Dynasty around 1332–1323 BC.

What exactly was found inside King Tut’s tomb? And is the curse of King Tut’s tomb real?

In the article below, World History Edu provides a snapshot of the continuing fascination with King Tutankhamun and his burial place.

Early Life and Reign of Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun ascended to the throne at a very young age, around 9 or 10, and his reign lasted about ten years until his death at around 19. His rule came at a tumultuous time in Egyptian history, during the aftermath of the religious revolution instigated by his predecessor, Akhenaten, who had upended centuries of religious tradition by imposing the worship of a single god, Aten.

After Akhenaten’s death, there was a return to the traditional polytheistic belief system and the restoration of Amun as the supreme god. Tutankhamun’s short reign was marked by this restoration, a fact celebrated in his epithet, “Living Image of Amun.”

In a significant move during the third year of his reign, Tutankhaten changed his name to Tutankhamun, and his queen’s name from Ankhesenpaaten to Ankhesenamun, signaling a definitive shift back to the worship of Amun, the traditional chief deity of the Egyptian pantheon. Image: The mask of Tutankhamun.

Rediscovery of the Tomb

The rediscovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb was particularly significant because it was one of the few royal tombs that had been left largely intact by grave robbers.

Hidden beneath the debris in the Valley of the Kings and overshadowed by the tomb of Ramses VI, it escaped the widespread looting that had plagued many other royal tombs over the millennia.

Howard Carter, an English archaeologist, had been searching for the tomb for several years under the patronage of Lord Carnarvon, a British aristocrat. On November 4, 1922, Carter’s team discovered steps leading to Tutankhamun’s tomb.

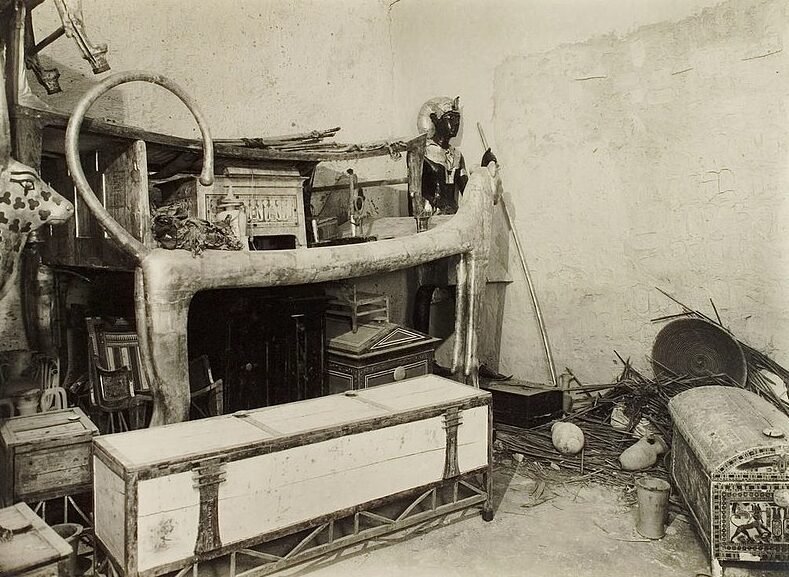

By November 26, they had breached the tomb’s entrance and caught their first glimpse of its contents. Carter’s famous message to Carnarvon, “Yes, wonderful things!” upon observing the antechamber, underscored the significance of the find.

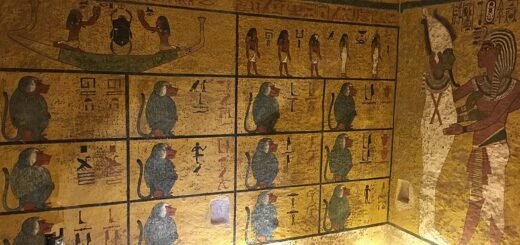

Since its rediscovery in the early 20th century, the tomb of Tutankhamun has provided an unparalleled glimpse into the material culture and burial practices of the New Kingdom of Egypt. Image: The inside section of the tomb.

The Tomb’s Contents

The tomb was relatively small but contained an astonishing array of items intended to serve the king in his afterlife. Over 5,100 artifacts were recovered, including golden chariots, thrones, beds, weapons, and a vast array of jewelry and statuettes.

The most iconic discovery was the pharaoh’s sarcophagus containing three nested coffins, the innermost being made of solid gold, and his famous gold funerary mask, which has become one of the most well-known symbols of ancient Egypt.

The layout of the tomb was typical of the period, consisting of four main rooms: the antechamber, the burial chamber, the treasury, and the annex. Each of these rooms was filled with artifacts meant to provide for the pharaoh in his journey through the underworld. This included the Book of the Dead, which was intended to guide Tutankhamun in the afterlife.

Scientific Insights and Further Discoveries

The examination of Tutankhamun’s mummy revealed significant information about his health and life. Studies suggest that Tutankhamun was frail and had several diseases, possibly due to inbreeding common among the Egyptian royalty. DNA tests and CT scans indicated that he suffered from malaria and a degenerative bone condition, which might have led to his early death.

The examination of artifacts from the tomb has also provided insights into the craftsmanship and artistic practices of the time. Detailed analysis of the materials used, such as the composition of the paints and metals, has offered clues into the trade networks and technological capabilities of Ancient Egypt.

Tutankhamun, often colloquially known as “King Tut,” became globally renowned following the 1922 discovery of his tomb by a team led by British Egyptologist Howard Carter, funded by British aristocrat George Herbert, Lord Carnarvon. Image: A 1992 photo of an antechamber of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

The Curse of the Pharaohs

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb is also shrouded in myths, particularly the legend of the “Curse of the Pharaohs,” which is believed to bring ill fortune to those who disturb the tombs of Ancient Egyptian rulers.

This myth gained traction due to the untimely deaths of several individuals connected to the tomb’s discovery, most notably Lord Carnarvon, who died under mysterious circumstances shortly after the tomb was opened.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

The global fascination with Tutankhamun has never waned. Exhibitions of Tutankhamun’s treasures tour the world, drawing millions of visitors. The boy king’s death mask remains a popular symbol of ancient Egypt, its appeal spanning beyond academic and historical circles into popular culture and media.

FAQs about King Tut and his tomb

Who was King Tut’s father?

Tutankhamun, originally named Tutankhaten, was born in the late Eighteenth Dynasty during the reign of Akhenaten, a period marked by radical religious reform.

Pharaoh Akhenaten introduced Atenism, worship centered on the sun disk, Aten, and moved Egypt’s capital to Amarna, a site that later defined this era as the Amarna Period. This shift represented a significant departure from traditional polytheistic practices, influencing the religious and political landscape of ancient Egypt profoundly.

What did his name mean?

Tutankhamun’s original name, Tutankhaten, means “living image of Aten,” reflecting the worship of the sun disk Aten under his father Akhenaten’s rule.

After Akhenaten’s death, the traditional polytheistic religion was restored, leading to Tutankhamun’s name change to “living image of Amun,” aligning him with Amun, a major deity in the Egyptian pantheon. This name change symbolized the religious shift back to the worship of Amun and the rejection of Atenism.

What was King Tut’s early reign like?

At the outset of his reign as King Tutankhaten, the royal court remained in Amarna, the city established by his predecessor and father, Akhenaten, as a center for the worship of the sun disk, Aten.

Early artifacts from Tutankhaten’s tomb indicate that Aten was still recognized during this time. However, there are significant indications that Tutankhaten’s court was making efforts to reconcile Atenism with the traditional polytheistic religion of Egypt, evidenced by a gradual reduction of activity in Amarna within the first four years of his reign.

This period marked a pivotal reversal of Akhenaten’s religious reforms. Due to Tutankhaten’s youth, it is widely believed that these changes were driven by his advisors rather than by the young king himself.

How did King Tut try to restore the worship and supremacy of the god Amun?

King Tut’s return to orthodoxy is starkly outlined in the Restoration Stela, likely from the fourth year of Tutankhamun’s reign. The stela describes the Amarna Period as a disastrous time when the temples and estates of the gods from Elephantine to the Delta had fallen into disrepair, and communication with the deities was severed. It announces the rebuilding of these traditional cults and the restoration of priests and temple staff to their former roles, signifying a formal restoration of the old religious structures and practices.

Subsequently, the royal court left Amarna to reestablish Memphis as the central hub of royal administration, continuing the trend set by earlier pharaohs of governing from this strategic location. With the restoration of Amun as the supreme god, Thebes regained its status as the primary religious center of Egypt.

Economically and diplomatically, Egypt was weakened by Akhenaten’s isolationist policies. Tutankhamun worked diligently to mend these fractures, particularly restoring relations with international powers like the Mitanni, as evidenced by the diverse gifts from various nations found in his tomb. Although his reign saw military engagements with Nubians and Asiatics—victories recorded in his mortuary temple at Thebes—Tutankhamun managed to maintain an undefeated military record, a testament to his efforts to stabilize and strengthen Egypt.

In his third year, Tutankhamun decisively ended the worship of Aten, reinstating Amun as the supreme deity and revitalizing its priesthood with traditional privileges. He moved the capital back to Thebes, abandoning Akhetaten. Significant building efforts were undertaken, particularly at Karnak where he enhanced the sphinx avenue leading to the Mut temple.

At Luxor, he completed Amenhotep III’s entrance colonnade. Tutankhamun also enriched the cults of Amun and Ptah, commissioning new deity statues and splendid processional barques, highlighting his commitment to restoring and embellishing traditional religious practices.

Tutankhamun’s fame stems largely from his intact tomb and the global exhibitions of its treasures. Welsh American Jon Manchip White notes the foreword to the 1977 edition of Howard Carter’s The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun that King Tut “who in life was one of the least esteemed of Egypt’s Pharaohs has become in death the most renowned”. Image: Sign to Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Who were King Tut’s successors?

King Tutankhamun was succeeded by his vizier, Ay, who likely was very old upon ascending the throne.

Ay’s brief reign was followed by that of Horemheb, previously Tutankhamun’s commander-in-chief.

Horemheb’s rule marked the full restoration of the traditional ancient Egyptian religion, dismantling the changes of the Amarna Period initiated by Akhenaten. Also, Horemheb claimed many of Ay and Tutankhamun’s projects as his own and worked to erase the memory of previous rulers from the Amarna Period, reestablishing the worship of the traditional pantheon and distancing the empire from the monotheistic experiment of his predecessors.

Horemheb would appoint Ramesses I, a military officer, as his successor. Ramesses I’s grandson, Ramesses II, would become a prominent pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty.

Where is King Tut’s tomb located?

The tomb is located in the Valley of the Kings, near the modern town of Luxor in Egypt.

What artifacts were discovered in King Tut’s tomb?

Although the tomb had been subject to ancient robberies, it remarkably retained much of its original contents, including Tutankhamun’s undisturbed mummy. This find, which included over 5,100 artifacts, sparked a massive resurgence of public interest in ancient Egypt.

The discovery was covered extensively by the global press, making Tutankhamun an international symbol of ancient Egyptian culture and history. His golden mask, now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, remains one of the most iconic representations of ancient Egypt.

Some of his treasures have been exhibited worldwide since the Egyptian government began allowing international tours in 1961, each time drawing unprecedented public response.

Why was the tomb so well preserved?

The tomb’s location was hidden and covered by debris from later tomb constructions, which helped it escape the notice of many tomb robbers throughout the centuries.

Was King Tut’s tomb really cursed?

For many years, the “curse of the pharaohs” captivated public imagination, often hyped by newspapers to boost sales following the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

This myth was underscored by the early death of several tomb visitors, most notably George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, who died on April 5, 1923—just five months after the tomb’s entrance was found. Carnarvon’s death was due to pneumonia following a facial erysipelas infection, exacerbated by his frail health from a 1901 car accident. His already weakened condition was further stressed by the excavation activities, making him susceptible to severe infection. In 1903, seeking a healthier climate on his doctor’s advice, Carnarvon traveled to Egypt, where he developed an interest in Egyptology.

A study examining the fate of the 58 people present at the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb and sarcophagus found that only eight died within twelve years of the event, challenging the myth of a deadly curse.

Regarding Howard Carter’s death in 1939, investigations revealed that the famed Egyptologist died of lymphoma. He was 64, and his demise came 17 years after the tomb’s discovery.

Among the last survivors were Lady Evelyn Herbert, Lord Carnarvon’s daughter, who entered the tomb in 1922 and lived another 57 years, dying in 1980.

American archaeologist J.O. Kinnaman passed away in 1961, almost four decades after the tomb’s opening.

These extended lifespans further debunk the notion of a curse associated with the tomb.

The deaths of some individuals associated with the tomb’s excavation have fueled legends of the “curse of the pharaohs,” attributed to the misfortunes that befell them under mysteriously similar circumstances. Image: A 1922 picture of workers at the site of the tomb.