The Moirai: The Personifications of Destiny in Greek Mythology

The Moirai, often known as the Fates in Greek mythology, are among the most intriguing and mysterious deities in ancient Greek religion. These three goddesses—Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos—were believed to control the destiny of all beings, both mortal and divine.

Their influence extended to the very fabric of life itself, determining its beginning, its length, and its inevitable end. The Moirai were seen as the personifications of fate, playing an essential role in the ancient Greek understanding of life’s course and the natural order of the universe.

READ MORE: Major Events in Greek Mythology

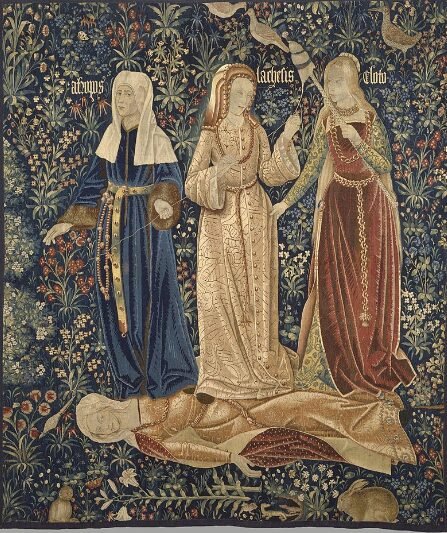

In ancient Greek mythology, the Moirai, also called the Fates, were the deities of destiny, responsible for ensuring that both gods and humans lived according to their predetermined paths. Image: The three Moirai, or Triumph of Death, Flemish tapestry, c. 1520 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London, England).

In the article below, World History Edu explores their origins, roles, cultural significance, and parallels in other mythologies, as well as their lasting influence on Western thought.

Etymology and Origins of the Moirai

The word “Moirai” comes from the Greek μοῖρα, which means “lot” or “portion.” This reflects the belief that life was essentially a portion of the universe’s totality, divided and allotted to each individual at birth.

The concept of “moira” also implies a part of something larger—whether it be one’s share of life or of destiny. The term is related to other Greek words, such as meros (part) and moros (doom), underscoring the idea that life is preordained and cannot be changed. This theme of predetermination is central to the role of the Moirai, who dispense a “portion” of life and experience to every person.

The Moirai have ancient roots in Greek mythology. Some scholars believe that their origins predate even the Olympian gods, tying them to older, more primal forces of the universe.

The Moirai’s power was immense, as they were believed to operate beyond the control of even the gods, although in some myths, Zeus had limited influence over them.

In some versions of Greek cosmogony, the Moirai are said to be the daughters of Nyx, the goddess of night, which further connects them to the more ancient and elemental aspects of the cosmos.

In later myths, they are often considered the daughters of Zeus and Themis, the goddess of divine law and order. The blending of these two origin stories highlights the dual nature of the Moirai: both primordial forces of destiny and enforcers of the moral order sanctioned by the gods.

Image: Roman-era bronze statuette of Nyx velificans or Selene (Getty Villa)

Roles and Functions of the Moirai

The Moirai are traditionally depicted as three sisters, each with a specific role in determining the fate of individuals:

Clotho (The Spinner)

Bas relief of Clotho, lampstand at the U.S. Supreme Court, Washington, D.C.

Clotho is responsible for spinning the thread of life. This thread symbolizes an individual’s lifespan and the essence of their existence. As the spinner, Clotho creates life, determining when it begins. Her spindle represents the start of each person’s journey through life, and her role emphasizes the fragility and malleability of human existence.

Lachesis (The Allotter)

Bas relief of Lachesis at the U.S. Supreme Court, Washington, D.C.

Lachesis measures the thread of life spun by Clotho. She determines the length of the thread, signifying the amount of time each individual has on earth. Her role as the allotter underscores the idea that life is finite and that each person’s destiny is predetermined. Lachesis also decides what each individual will experience during their lifetime, essentially laying out the path they will follow.

Atropos (The Inflexible)

Bas relief of Atropos depicting her cutting the thread of life.

Atropos is the most feared of the three sisters, as she is the one who cuts the thread of life. Her role signifies death and the inevitable end that comes to all living things. Atropos is often depicted with shears, a symbol of the finality of her decisions. Once she cuts the thread, there is no turning back—death is certain, and nothing can alter that fate.

Clotho, the spinner, spun the thread of life; Lachesis, the allotter, determined the length and destiny of each life; and Atropos, the inevitable, severed the thread, symbolizing death. Image: A late second-century Greek mosaic from the House of Theseus in Cyprus depicts the Moirai—Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos—behind Peleus and Thetis.

Together, the Moirai control the entire course of life from birth to death. They represent the inescapable nature of fate, a central belief in Greek mythology. The Moirai’s power is so great that even the gods themselves are subject to their decisions. While some myths suggest that Zeus, the king of the gods, has some influence over the Moirai, their ultimate authority is rarely questioned. This underscores the Greeks’ belief in the inevitability of destiny and the limitations of divine power when it comes to changing the course of a person’s life.

Cultural Significance of the Moirai in Greek Mythology

In ancient Greek culture, the Moirai were revered as powerful deities who ensured that the natural order of life was maintained. They were often associated with justice and balance, reflecting the Greek belief in a cosmic order that governed all things. The concept of fate in Greek mythology is deeply intertwined with ideas of justice and morality. Those who attempted to cheat fate or overstep their boundaries were often punished, as this was seen as an affront to the natural order.

One of the most famous stories involving the Moirai is that of Meleager, a hero whose fate was determined by a piece of burning wood. At Meleager’s birth, the Moirai appeared to his mother, Althaea, and foretold that he would live only as long as a specific log remained unburned. Althaea hid the log to protect her son, but in a fit of rage later in life, she threw it into the fire, sealing Meleager’s fate. This story illustrates the Moirai’s control over life and death, as well as the tragic consequences of trying to escape destiny.

The Moirai were also invoked in rituals and offerings, particularly those related to childbirth and marriage. It was common for brides to offer locks of their hair to the Moirai, symbolizing their submission to fate. Women also swore oaths by the Moirai, underscoring their reverence and recognition of the Fates’ power in determining life’s outcomes.

READ MORE: Most Famous Heroes and Heroines in Greek Mythology

The Moirai in Literature and Art

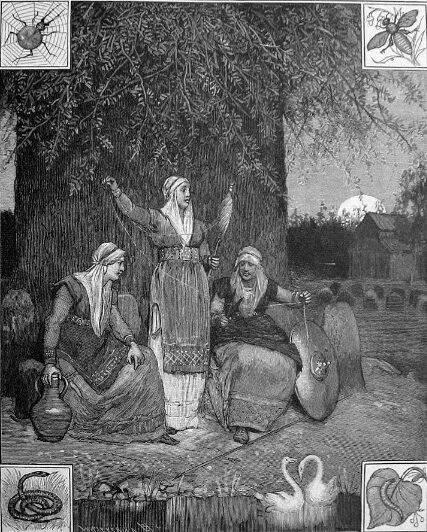

Macbeth and Banquo encounter the three weird sisters in a woodcut from Holinshed’s Chronicles.

The Moirai appear in many ancient Greek literary works, often symbolizing the inevitability of fate and the consequences of human actions.

In The Iliad and The Odyssey, attributed to Homer, fate plays a central role in the unfolding of events. Characters often confront their fates with a sense of resignation, knowing that no one—not even the gods—can alter what is destined to happen. For instance, in The Iliad, the warrior Hector is fated to die at the hands of Achilles, and despite his bravery, he cannot escape this outcome.

In Plato’s Republic, the Moirai are depicted as singing with the Seirenes, each sister representing different aspects of time: Clotho sings of the present, Lachesis of the past, and Atropos of the future. This portrayal emphasizes their role as weavers of destiny and their intimate connection to the passage of time.

The Moirai were also frequent subjects of ancient Greek art. They were typically depicted as solemn, authoritative figures, often holding their symbolic tools: Clotho’s spindle, Lachesis’ measuring rod, and Atropos’ shears. Their presence in art reinforces their role as controllers of fate and reminders of life’s transience.

Parallels in Other Cultures

The Norns weave fate’s threads at Yggdrasil‘s base, the world tree.

The concept of fate controlled by three goddesses is not unique to Greek mythology. Many other cultures have similar figures who oversee destiny and ensure the natural order is maintained.

- Norse Mythology (The Norns): In Norse mythology, the Norns are three female beings who, like the Moirai, control the destiny of gods and men. Their names are Urðr (fate), Verðandi (becoming), and Skuld (debt), and they are believed to represent the past, present, and future. The Norns weave the threads of fate, and their decisions cannot be undone, similar to the Moirai’s control over life and death.

- Roman Mythology (The Parcae): The Roman equivalent of the Moirai are the Parcae or Fata. Their roles mirror those of Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos, as they control birth, life, and death. In Roman mythology, they are also associated with the goddess Fortuna, who embodies luck and chance, highlighting the Romans’ belief in the unpredictability of life’s outcomes.

- Baltic Mythology (Laima and Her Sisters): In Lithuanian and Latvian mythology, Laima is the goddess of fate, responsible for determining a person’s lifespan and future. Laima is often accompanied by her sisters, Kārta and Dēkla, who also play roles in shaping destiny. Like the Moirai, Laima and her sisters oversee key moments in a person’s life, particularly birth, marriage, and death.

- Egyptian Mythology (Maat): In ancient Egypt, the goddess Maat represented truth, balance, and cosmic order. While not directly responsible for fate in the same way as the Moirai, Maat’s role in maintaining the balance of the universe and judging the souls of the dead in the afterlife is closely aligned with the Greek concept of fate. In Egyptian mythology, the heart of the deceased is weighed against Maat’s feather to determine whether they will achieve eternal life or face destruction.

The Weighing of the Heart in the Hall of Maat

The Moirai and the Gods

Image: Prometheus creates man: Clotho, Lachesis with Poseidon, and likely Atropos with Artemis appear on a Roman sarcophagus (Louvre).

While the Moirai are often depicted as independent forces, their relationship with the gods, particularly Zeus, is complex. Some myths suggest that Zeus, as the king of the gods, has the power to influence or even override the decisions of the Moirai.

For example, in the story of Sarpedon, Zeus’ son, the king of the gods debates whether to save Sarpedon from his fated death on the battlefield. Ultimately, Zeus chooses to let fate run its course, respecting the authority of the Moirai.

In contrast, other myths portray the Moirai as completely independent from the gods, acting according to the natural order rather than divine will. This tension between divine power and the immutability of fate reflects the ancient Greek worldview, where even the most powerful gods were bound by the cosmic laws governing the universe.

READ MORE: Sons of Zeus in Greek Mythology

The Moirai’s Lasting Influence

The Moirai’s role as the personifications of fate and destiny has had a lasting impact on Western thought, particularly in literature and philosophy. The idea of fate as an inescapable force is a common theme in many works of classical literature, from Greek tragedies to Roman epics. The concept of life as a thread that is spun, measured, and cut has become a powerful metaphor for the fragility of human existence.

In more modern literature, the Moirai continue to inspire interpretations of fate and destiny. For example, in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the Weird Sisters (or Three Witches) are inspired by the Moirai, foretelling Macbeth’s rise to power and his eventual downfall. Their prophecies highlight the tension between free will and predestination, a theme that echoes the ancient Greek understanding of fate.

Philosophers throughout history have also grappled with the idea of fate. The Stoics, in particular, embraced the concept of fate as an inevitable force that should be accepted with resignation and tranquility. This philosophy, rooted in ancient Greek ideas about destiny, has influenced later thinkers and continues to shape discussions about free will, determinism, and the nature of human existence.

Conclusion

The Moirai are central figures in Greek mythology, embodying the ancient Greek understanding of destiny as a predetermined and inescapable force. Through their roles as the spinner, measurer, and cutter of the thread of life, they symbolize the fragility of existence and the inevitability of death. Their influence extends beyond Greek mythology, with parallels in Norse, Roman, Baltic, and Egyptian cultures, reflecting a shared human fascination with the concept of fate.

The Moirai’s legacy lives on in literature, philosophy, and art, where they continue to inspire reflections on life’s brevity and the mysterious forces that govern our existence. Whether viewed as goddesses of destiny or as metaphors for life’s natural order, the Moirai remain timeless symbols of the human experience and the delicate balance between free will and fate.

Frequently Asked Questions

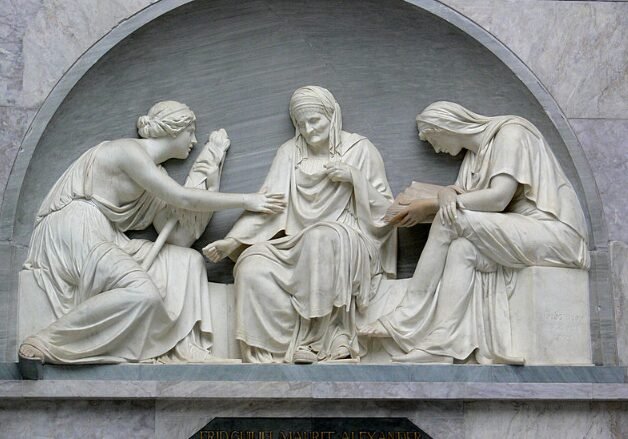

The three Moirai, relief, grave of Alexander von der Mark [de] by German Sculptor Johann Gottfried Schadow (Old National Gallery, Berlin)

What is the origin of the term “Moirai”?

The term “Moirai” comes from the Greek word μοῖρα, meaning “lots” or “destinies.” It implies a portion or part of the whole and is linked to the Greek words meros (part) and moros (fate). These are derived from the Proto-Indo-European root (s)mer, meaning “to allot or assign.”

Who were the Moirai in Greek mythology?

The Moirai, also known as the Fates, were three sisters: Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos. They controlled the destinies of all beings, mortal and divine. Clotho spun the thread of life, Lachesis measured its length, and Atropos cut the thread, determining the moment of death.

What role did the Moirai play in Roman mythology?

In Roman mythology, the Moirai were known as the Parcae or Fata. Their roles were similar to their Greek counterparts, overseeing fate and destiny. Their names in Roman mythology were Nona, Decima, and Morta.

What similar figures existed in other cultures’ mythologies?

In Norse mythology, the Norns ruled destiny, representing the past, present, and future. In Celtic mythology, the Matres or Matrones were fate goddesses. In Lithuanian mythology, Laima, with her sisters Kārta and Dēkla, prophesied the destinies of newborns.

The trio of Fates (Norn) that live near Urdarbrunnr (Urdr’s Well) are known for deciding the fates of people. Image: Norns (1832) from Die Helden und Götter des Nordens, oder das Buch der Sagen

What was Asha’s role in Zoroastrianism, and how is it related to the Moirai?

In Zoroastrianism, Asha represented truth, righteousness, and cosmic order, similar to the Moirai’s role in Greek mythology. Asha was derived from the same Proto-Indo-European root as the Vedic Rta, which also symbolized universal order.

What responsibilities did each of the three Moirai have?

Clotho, the spinner, oversaw birth and spun the thread of life. Lachesis, the allotter, measured the length of life, determining each person’s destiny. Atropos, the most feared, cut the thread, deciding the moment of death.

How were the Moirai depicted in literature?

The Moirai appeared in many literary works, such as Dante’s Divine Comedy and Shakespeare’s Macbeth, where they were depicted as controllers of fate. They also played a central role in Greek literature, such as in Hesiod’s works, where they punished both mortals and gods.

What rituals or practices were associated with the Moirai in Greek culture?

In Greek culture, the Moirai were invoked during rituals and offerings. Brides in Athens offered locks of hair to them, and women swore oaths by their names. They were believed to appear three nights after a child’s birth to determine its fate.

How did Zeus interact with the Moirai according to Greek myths?

Zeus had limited authority over the Moirai. For example, in the myth of Hector and Achilles, Zeus used scales to weigh their destinies, but he could not alter the fate that the Moirai had already spun.

How did Greek philosophers and poets view the Moirai?

Greek philosophers and poets explored the Moirai’s role in fate and moral responsibility. In Plato’s Republic, the Moirai sing about past, present, and future events, representing the unfolding of destiny. Hesiod emphasized their moral purpose in punishing those who overstepped their destined roles.

How did the Moirai influence later periods in Greek culture?

The Moirai continued to influence Greek culture during the classical period. They were worshipped in temples, depicted in art, and remained central to the Greek understanding of fate, life’s fragility, and the inevitability of death.

What was the Moirai’s significance in Mycenaean religion?

In Mycenaean religion, which heavily influenced later Greek beliefs, fate was closely associated with divine beings and was considered an inevitable force governing life and death.

The Fates represented this in Greek thought, embodying the inescapable destiny that every being, divine or mortal, had to follow. The threads they spun symbolized life’s fragility and the inevitability of death, making the Moirai central figures in the ancient understanding of life’s natural order. Image: The Three Fates by German artist Paul Thumann, 19th century