Why did Cleopatra’s father Pharaoh Ptolemy XII pay huge bribes to Roman politicians?

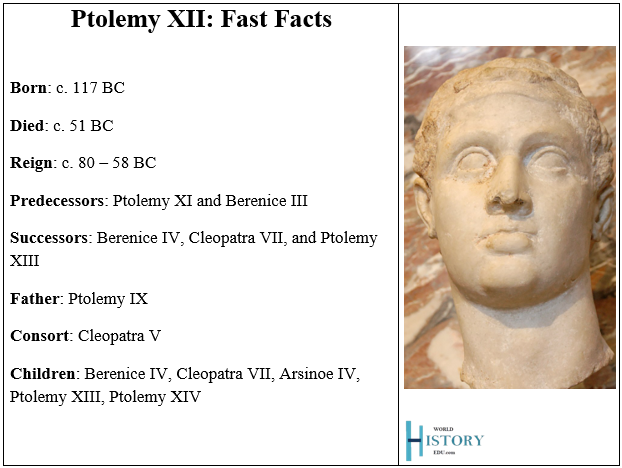

Ptolemy XII Auletes, known as the father of the renowned Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt, had a reign marked by political upheaval, experiencing both exile and subsequent restoration. Pictured: A bust of Ptolemy XII is located in the Department of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris.

Summary

Ptolemy XII Auletes, Cleopatra’s father, paid significant bribes to Roman politicians due to the precarious political environment of his reign and his dependence on Roman support to secure and maintain his throne.

Egypt was a wealthy and strategic region, and maintaining a friendly ruler in Egypt was of significant interest to Rome. Ptolemy XII needed Roman support to secure his rule against internal opposition and potential usurpers. By bribing key Roman figures, he aimed to ensure their backing and protection.

Ptolemy XII was expelled from power and had to flee to Rome. The bribes were a means to secure Roman military support to regain his throne. Romans, in turn, were interested in restoring a compliant ruler who would safeguard Roman interests in Egypt.

The political landscape of Rome during this period was characterized by alliances and enmities between influential leaders. Ptolemy’s bribes were aimed at forging alliances with powerful Roman leaders like Pompey and Julius Caesar to gain their support and protection.

After regaining his throne with Roman assistance, Ptolemy XII was in substantial debt to Roman creditors. The bribes can also be seen as part of his strategy to manage relationships with these creditors and potentially alleviate some of his debt burdens.

READ MORE: Notable Accomplishments of Queen Cleopatra VII

The bribes were a pragmatic approach to navigate and manage the complex political interdependencies between Ptolemy XII’s reign in Egypt and Roman imperial interests. Image: Relief of Ptolemy XII from the double temple at Kom Ombo

Origin story

Ptolemy XII, living under the shadow of Rome’s growing power, faced precarious circumstances due to his predecessor, Ptolemy X’s, will, which left Egypt to Rome if no legitimate heirs survived him. While Rome hadn’t capitalized on this opportunity initially, the potential threat pressed the subsequent Ptolemies, including Ptolemy XII, to maintain diplomatic prudence and amicability towards Rome to secure their reign and the dynasty’s continuity.

Ptolemy XII upheld a pro-Roman policy, striving to safeguard his position amid escalating Roman influences and intimidations. Rome’s influence and its designs on Egypt were evidenced when, in 65 BC, Marcus Licinius Crassus advocated for Rome’s annexation of Egypt, although the proposition was thwarted by oppositions from Quintus Lutatius Catulus and Cicero.

Responding to these pressures, Ptolemy XII invested considerably in influencing Roman politicians to endorse his interests, facilitating relations with key Roman figures like Pompey the Great by extending significant support and rewards, including a golden crown and cavalry assistance, despite Pompey’s refusal to intervene in a purported revolt in Egypt.

To amass the substantial funds for these bribes, Ptolemy XII elevated taxes, instigating discontent and protests among his subjects, and incurred loans from Roman financiers, which further accentuated Rome’s control over his regime and accentuated the relevance of Egypt’s fate in Roman politics.

In 60 BC, Ptolemy XII ventured to Rome to negotiate the official acknowledgment of his rule with the First Triumvirate—Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar. Substantial monetary incentives were exchanged to solidify a formal alliance, earning Ptolemy XII a formal recognition from the Roman Senate and a distinguished position as a friend and ally of the Roman people in 59 BC.

The inherent precariousness in this alliance became manifest when, in 58 BC, Rome annexed Cyprus, leading to the suicide of its ruler, Ptolemy XII’s brother. Ptolemy XII’s lack of response consolidated Cyprus as a Roman province until its brief restoration to Ptolemaic authority by Julius Caesar in 48 BC.

READ MORE: Most Notable Roman Generals and their Accomplishments

Roman politicians and generals Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey were members of the First Triumvirate, an unofficial political alliance that wielded immense power and wealth in the middle part of the 1st century BC.

What were the repercussions of his actions?

Ptolemy XII’s long-standing bribery policy and heavy taxation were deeply unpopular among Egyptians, especially after the failure showcased by the annexation of Cyprus. This dissatisfaction culminated in Ptolemy XII being forced to abdicate the throne and flee from Egypt. Berenice IV, his daughter, replaced him, ruling initially with Cleopatra Tryphaena and then alone after Tryphaena’s death.

Ptolemy XII sought refuge in Rome, probably accompanied by his daughter Cleopatra VII. On his way to Rome, he interacted with Cato the Younger in Rhodes but received no substantial support. Once in Rome, Ptolemy XII worked towards his restitution to the throne, despite facing opposition within the Roman Senate. Pompey, a staunch ally, housed the exiled king and championed his restoration in the Senate.

Roman creditors, who had lent substantial amounts to Ptolemy, realized that the restitution of the king was crucial for the repayment of their loans. Pressures from these creditors and the Roman public forced the Senate in 57 BC to decide on restoring Ptolemy, although a direct military intervention was avoided due to prophecies in the Sibylline books warning against such an action.

The Egyptians, on learning about potential Roman intervention, were disgruntled at the thought of Ptolemy XII’s return. Envoys were sent from Egypt to Rome to present their opposition against Ptolemy XII’s restoration, but Ptolemy XII allegedly orchestrated the assassination of the leader of these envoys, Dio of Alexandria, and eliminated most of the other protesters before they could reach Rome.

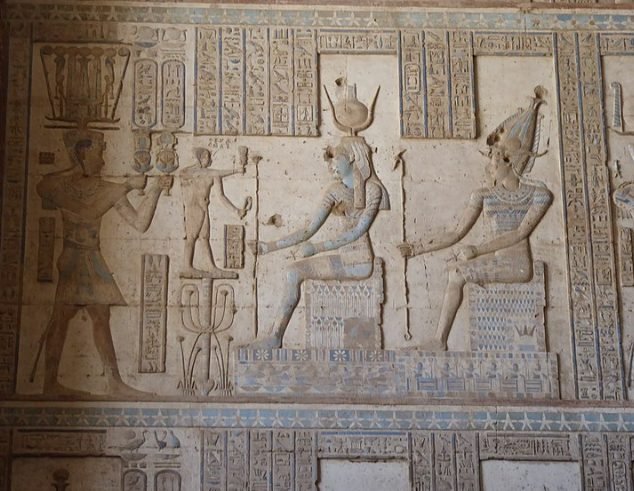

This episode in Ptolemaic and Roman history is illustrative of the intricate politics, public resentments, and behind-the-scenes machinations that defined the interactions between the two civilizations, and it paved the way for further Roman influence and eventual control over Egypt. Image: Ptolemy XII before Isis and Osiris, at the Hathor Temple, Dendera

READ MORE: Most Famous Ancient Egyptian Goddesses and their significance

The Restoration of Ptolemy XII to the throne of Egypt

In 55 BC, after his removal from the throne of Egypt, Ptolemy XII managed to recover his position by paying Aulus Gabinius 10,000 talents to invade Egypt. Gabinius successfully defeated the Egyptian forces and reinstated Ptolemy XII to power between January and June of 55 BC. Upon his restoration, Ptolemy XII had his daughter Berenice IV, who had taken over the rulership, executed along with her supporters.

However, his reign was deeply influenced by Roman interventions, with around two thousand Roman soldiers and mercenaries, known as the Gabiniani, supporting his rule. This, combined with his indebtedness to Roman creditors, allowed Rome to maintain a significant degree of control over his rule.

Facing demands for repayment from Roman creditors and a financially strained treasury, Ptolemy XII appointed his main creditor, Gaius Rabirius Postumus, as the minister of finance, transferring the public’s resentment over financial strains to Rabirius and away from himself. Rabirius, having direct access to Egypt’s financial resources, exploited the land heavily, causing Ptolemy XII to imprison him temporarily for his own safety and later allowing him to escape back to Rome, where he faced accusations but was likely acquitted.

Ptolemy XII also debased the coinage to manage the financial crisis, severely affecting its value by the end of his reign. Ptolemy XII died in 51 BC, leaving a will that designated his daughter Cleopatra VII and her brother Ptolemy XIII as co-rulers of Egypt and made the people of Rome the executors of his will. Pompey, his Roman ally, approved the will, ensuring the continuation of the Ptolemaic line, but also perpetuating Rome’s influence and interests in Egypt.

In order to restore Ptolemy XII to the throne of Egypt, Pompey persuaded Aulus Gabinius, who was the Roman governor of Syria at the time, to launch a military invasion in Egypt. This invasion was executed in the spring of 55 BC. During this military campaign, Mark Antony, one of the officers serving under Gabinius, played a pivotal role. He not only thwarted Ptolemy XII’s attempt to execute the residents of Pelousion who had opposed him but also retrieved the body of Archelaos, the husband of Berenice, following his death in battle. Image: Bust of Pompey the Great

Ptolemy XII’s return to power

Pompey, the Roman general and ally of Ptolemy XII, persuaded Aulus Gabinius, who was then the Roman governor of Syria, to lead a military intervention in Egypt with the goal of reinstating Ptolemy XII to the throne. This military campaign occurred in the spring of 55 BC. During this invasion, Mark Antony, who was serving as one of the officers under Gabinius, played a significant role in safeguarding the citizens of Pelousion from Ptolemy XII’s retaliatory actions and also recovered the body of Archelaos, Berenice’s husband, who was slain in battle.

Although Antony claimed to have fallen in love with Cleopatra during this time, their romantic involvement didn’t commence until 41 BC. Antony and Cleopatra (1883) by Dutch painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema depicting Mark Antony’s meeting with Cleopatra in 41 BC.

Mark Antony is said to have developed a fondness for Cleopatra around this time, although their romantic entanglement didn’t commence until 41 BC. Upon gaining power, Ptolemy XII appointed Cleopatra as his co-ruler and regent in 52 BC and, in his will, declared her and his son Ptolemy XIII as joint successors. Ptolemy XII passed away by March 22, 51 BC, and one of Cleopatra’s initial acts as queen was the ceremonial restoration of the sacred Buchis bull in Hermonthis, Egypt.

It is speculated that Cleopatra may have entered into a marital union with her brother, Ptolemy XIII, although there is uncertainty regarding whether the marriage transpired before their subsequent rivalry and military conflict during the Alexandrine war.

Following his restoration to the throne, Ptolemy XII declared daughter Cleopatra his co-ruler and regent in 52 BC and specified her and his son, Ptolemy XIII, as joint heirs in his will. Ptolemy XII passed away by the 22nd of March 51 BC. Cleopatra’s first documented act as the queen following his death was the restoration of the revered Buchis bull in Hermonthis, Egypt. Image: The Berlin Cleopatra is a Roman sculpture of Cleopatra wearing a royal diadem, mid-1st century BC (around the time of her visits to Rome in 46–44 BC). It was discovered in an Italian villa along the Via Appia. The sculpture is now located in the Altes Museum in Germany.

READ MORE: How did Rome conquer ancient Egypt?