Origin of ancestor worship in ancient China

Ancestor worship in ancient China was a deeply rooted tradition that permeated all aspects of Chinese society, from family life and politics to philosophy and religious practices. This practice was based on the belief that the spirits of deceased ancestors had the power to influence the fortunes of their descendants, either positively or negatively. As a result, living family members were expected to venerate their ancestors through various rituals and offerings to maintain harmony between the living and the dead.

The practice of ancestor worship not only reinforced familial ties and social stability but also provided a framework for understanding the cosmos and the individual’s place within it.

This long-standing tradition was closely linked to Confucian ideals, which emphasized filial piety, respect for elders, and the maintenance of familial hierarchies. Although the roots of ancestor worship can be traced back to the Shang and Zhou dynasties, its influence persisted for millennia, shaping the moral and spiritual foundations of Chinese culture.

A stone tortoise bears the “Stele of Divine Merits and Saintly Virtues”, erected in 1413 by the Yongle Emperor to honor his father, the Hongwu Emperor, at the Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum.

Origins and Evolution of Ancestor Worship

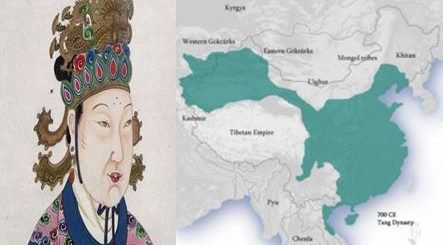

Early Beginnings: The Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE)

Ancestor worship in China can be traced to the Shang dynasty, where it played a crucial role in the religious and political framework of the society. The Shang kings were not only political leaders but also intermediaries between the living and the divine, communicating with ancestors and gods through elaborate divination rituals. Oracle bones, discovered in the ruins of the Shang capital at Anyang, provide valuable insights into these practices. These bones, often from oxen or turtles, were inscribed with questions to ancestors and heated until they cracked, with the resulting patterns interpreted as responses from the spirit world.

The practice of ancestor worship became more structured during the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), where the spirits of deceased ancestors were believed to reside in heaven and communicate with the living through shamans.

The Shang people believed that their ancestors could influence agricultural success, military victories, and the well-being of the kingdom. Therefore, elaborate rituals and offerings were performed to honor these spirits. Sacrifices of animals and, in some cases, humans were made to appease ancestral spirits, ensuring their favor and protection. Ancestor worship during the Shang period was not confined to the royal family but extended to all levels of society, though the scale and complexity of the rituals varied according to social status.

The Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE): Institutionalization of Rituals

With the advent of the Zhou dynasty, ancestor worship became more structured and aligned with emerging philosophical frameworks, particularly Confucianism. The Zhou rulers introduced the concept of the “Mandate of Heaven” (天命, Tiānmìng), which justified their rule by claiming divine approval. This cosmic order was believed to be maintained through proper rituals and moral governance, with ancestor worship playing a critical role in sustaining harmony between Heaven, Earth, and humanity.

During this period, the practice of offering sacrifices and performing rituals for ancestors became more codified. The Zhou dynasty formalized the use of ancestral temples (宗庙, zōngmiào), where lineage-specific rituals were conducted. These temples housed ancestral tablets inscribed with the names of deceased family members and served as a focal point for family devotion. Regular offerings of food, drink, and incense were made to honor the spirits, reinforcing the belief that ancestors continued to exist in the spiritual realm and maintained a vested interest in the welfare of their descendants.

Philosophical Foundations of Ancestor Worship

Confucianism and Filial Piety

Confucianism, the dominant philosophical and ethical system in ancient China, provided the moral foundation for ancestor worship. At the heart of Confucian thought was the concept of filial piety (孝, xiào), which emphasized respect, obedience, and care for one’s parents and elders. Confucius (c. 551–479 BCE) taught that the family was the cornerstone of society and that maintaining harmony within the family was essential for the stability of the state. Filial piety extended beyond death, requiring descendants to honor and care for their deceased ancestors through rituals and sacrifices.

Rooted in the belief that ancestral spirits maintained a continuous presence in the lives of their descendants, ancestor worship in ancient China fostered a sense of duty and reverence that transcended generations.

According to Confucian teachings, the proper performance of ancestral rites was not merely a religious obligation but also a demonstration of moral virtue and social propriety. Confucius argued that reverence for ancestors cultivated a sense of duty and responsibility within the family, which in turn promoted a well-ordered society. The practice of ancestor worship was thus an extension of the Confucian ideal of maintaining hierarchical relationships and ensuring the transmission of moral values across generations.

Daoism and the Cosmic Order

While Confucianism provided the ethical framework for ancestor worship, Daoism contributed a metaphysical dimension to the practice. Daoist philosophy, which emphasized harmony with the natural order (道, Dào), viewed ancestral spirits as part of the larger cosmic continuum. Daoist beliefs in the immortality of the soul and the cyclical nature of life and death reinforced the idea that ancestors retained a presence in the spiritual realm and could exert influence on the living.

Daoist rituals often incorporated elements of ancestor worship, such as the use of talismans, incantations, and offerings to appease wandering spirits and ensure their peaceful existence. Daoism also introduced the concept of yin and yang, the dual forces of nature that must be balanced to maintain harmony. Ancestor worship was seen as a means of restoring this balance by honoring the spirits of the dead and preventing them from becoming malevolent forces that could disrupt the natural order.

Ritual Practices and Offerings

Ancestral Tablets and Shrines

One of the central elements of ancestor worship in ancient China was the use of ancestral tablets, which served as symbolic representations of deceased family members. These tablets were typically housed in ancestral shrines or family altars, where they were venerated with offerings and prayers. Each tablet bore the name of the deceased and was believed to contain the spirit of the ancestor, serving as a conduit between the living and the dead.

Families conducted regular rituals at these shrines, particularly during important festivals such as the Qingming Festival (清明节, Qīngmíng jié), also known as Tomb-Sweeping Day. During this festival, families visited the graves of their ancestors, cleaned the tombs, and made offerings of food, incense, and paper money to ensure the continued well-being of the ancestral spirits. The act of maintaining ancestral tablets and performing these rituals reinforced the idea that the family was a continuous entity that transcended generations.

Offerings and Sacrifices

Offerings made to ancestors typically included food, wine, incense, and symbolic items such as paper money and miniature representations of household goods. These offerings were believed to sustain the spirits in the afterlife and ensure their continued favor. The choice of offerings was often guided by the preferences of the deceased, with families taking care to provide items that their ancestors had enjoyed during their lifetime.

In addition to regular offerings, special sacrifices were made on significant occasions such as weddings, births, and the New Year. These sacrifices, known as jìsì (祭祀), were elaborate ceremonies that involved the preparation of ceremonial feasts, the burning of incense, and the recitation of prayers. The head of the family, typically the eldest male, assumed the role of officiant, symbolizing the continuity of the family lineage and the preservation of ancestral ties.

Communication with Ancestral Spirits

Communication with ancestral spirits was a key aspect of ancestor worship, with various methods used to seek guidance, express gratitude, and request protection. Divination was one of the primary means of establishing contact with the spirit world, with practitioners using oracle bones, yarrow sticks, and later, the I Ching (易经) to interpret the will of the ancestors. Families also believed that dreams could serve as a medium through which ancestors conveyed messages or warnings.

In some cases, professional mediums or shamans were employed to communicate directly with ancestral spirits. These individuals, believed to possess special spiritual abilities, conducted rituals to invite the spirits into the human realm and relay their messages to the living. Such interactions reinforced the belief that ancestors maintained an active presence in the lives of their descendants and that their guidance was essential for the family’s prosperity.

Ancestor worship in ancient China originated during the Neolithic period, with the earliest evidence traced to the Yangshao culture (c. 6000–1000 BCE) in the Shaanxi Province.

Political and Social Implications of Ancestor Worship

Legitimizing Political Authority

Ancestor worship was not only a family-centered practice but also a powerful tool for legitimizing political authority. Chinese rulers, particularly during the Zhou and Han dynasties, traced their lineage to divine ancestors and used this connection to justify their right to rule. The performance of ancestral rites by emperors and high-ranking officials was seen as a means of maintaining cosmic harmony and ensuring the stability of the state.

The imperial court maintained ancestral temples where elaborate ceremonies were conducted to honor the spirits of previous dynasties and reinforce the ruler’s connection to the divine order. By emphasizing the continuity of the ruling lineage, ancestor worship served to consolidate political power and legitimize the authority of the emperor as the “Son of Heaven” (天子, Tiānzǐ).

Ancestral sacrifice in Zhejiang, China.

Reinforcing Social Hierarchies

Ancestor worship also played a significant role in reinforcing social hierarchies and maintaining patriarchal structures. The responsibility for performing ancestral rites was typically passed down through the male line, with the eldest son assuming the role of custodian of the family lineage. This patriarchal arrangement reflected the broader Confucian emphasis on hierarchical relationships and the subordination of women within the family structure.

Women were expected to participate in ancestor worship by supporting their husbands and sons in performing rituals, but they rarely assumed a central role in these ceremonies. The emphasis on male lineage and inheritance reinforced the notion that the family’s honor and continuity rested on the shoulders of its male members.

Decline and Adaptation of Ancestor Worship

The Influence of Buddhism

The introduction of Buddhism to China during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) introduced new concepts of death and the afterlife that gradually influenced traditional ancestor worship practices. Buddhism emphasized the idea of karma and reincarnation, which challenged the notion that ancestral spirits remained tied to the family lineage. As Buddhist monasteries gained influence, they began to offer alternative forms of ancestor veneration, such as dedicating merit to the deceased through charitable acts and prayers.

Despite these influences, ancestor worship remained a central aspect of Chinese culture, often blending with Buddhist practices. The incorporation of Buddhist elements, such as the use of chanting and the offering of vegetarian food, enriched and diversified the rituals associated with ancestor worship.

A Taoist-led ancestral worship ceremony takes place at the Great Temple of Zhang Hui in Qinghe, Hebei.

Persistence in Modern Times

Although the influence of ancestor worship waned during periods of political and social upheaval, such as the fall of the Qing dynasty and the Cultural Revolution, the practice never entirely disappeared. In contemporary China, ancestor worship continues to be observed, particularly during traditional festivals such as Qingming and the Hungry Ghost Festival (中元节, Zhōngyuán jié). Families still maintain ancestral tablets and offer prayers and sacrifices to honor their forebears.

The enduring nature of ancestor worship reflects its deep integration into Chinese cultural identity and its ability to adapt to changing social and political contexts. Today, ancestor worship serves as a symbolic link between past and present, reinforcing the importance of family continuity and cultural heritage.

Questions and answers

How did ancestor worship evolve during the Zhou dynasty?

During the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE), ancestor worship became more formalized and incorporated into state rituals. Royal ancestors were honored in elaborate temple complexes that defined the status of capital cities by the 4th century BCE. The belief that an individual had two souls, the po which ascended to heaven and the hun which remained in the body, necessitated regular offerings to prevent the hun from becoming a wandering spirit.

What was the relationship between the living and the dead in ancestor worship?

Ancestor worship was based on a reciprocal relationship where the living tended to the physical needs of their deceased relatives through offerings and sacrifices, while the ancestors protected and guided their descendants. Ancestors were regarded as part of the family and were kept informed of significant events such as births, marriages, and other milestones.

How was immortality connected to ancestor worship in ancient China?

The concept of immortality in Chinese tradition, known as shou or longevity, extended to the afterlife. Preserving the memory of ancestors through maintaining shrines, making offerings, and composing literary works ensured their spiritual immortality. During the Han dynasty (c. 202 BCE–220 CE), poems and inscriptions were commonly used to memorialize the deceased and perpetuate their legacy.

What rituals and sacrifices were involved in ancestor worship?

Ancestor worship began with a son’s expression of filial piety toward his father during life and continued after death through elaborate mourning practices known as the “Five Degrees of Mourning Attire.” Public monuments, such as stone steles inscribed with the names and achievements of the deceased, were erected to preserve their memory. Offerings at family cemeteries, temples, or household shrines included food, drink, and incense, while imperial ceremonies involved more elaborate rituals with musicians, dancers, and valuable gifts.

Through rituals, offerings, and communication with the spirit world, the Chinese people maintained a harmonious relationship between the living and the dead, ensuring the well-being of both family and state.

How did emperors reinforce their divine connection through ancestor worship?

Emperors maintained elaborate ancestral shrines to reinforce their divine connection through the Mandate of Heaven. The founder of the Han dynasty, Emperor Gaozu, had ancestral shrines in every commandery across the empire, requiring extensive resources and a staff of over 65,000 people to maintain them. Although the number of imperial shrines was eventually reduced, the practice continued to legitimize the emperor’s authority.

How did clan worship function within Chinese society?

Ancestor worship extended beyond individual families to clans, which shared a common surname and ancestral lineage. Clans maintained ancestral temples where ceremonies were conducted to honor the achievements of the group. Clan elders, granted legally recognized powers, ensured that ancestral graves were maintained and sacrifices were offered. Offerings were primarily devoted to senior males of the previous three generations, with emperors extending veneration to four generations.

What role did ancestral tablets play in household ancestor worship?

In ordinary households, ancestor worship centered around ancestral tablets that recorded the names and deeds of deceased relatives. These tablets were displayed in a dedicated room or placed on family altars, with the elder son responsible for maintaining them. After three generations, the tablets were either buried at the ancestor’s grave or placed in clan temples for safekeeping. They also played a role in wedding ceremonies, where brides bowed before them to signify acceptance into the new family.

What challenges did ancestor worship face over time?

Ancestor worship faced challenges with the introduction of Buddhism during the Han dynasty, which emphasized spiritual pursuits over family obligations. Monks, who renounced family ties, were not seen as exemplars of filial piety. Christian missionaries in the 17th century CE also condemned the practice, leading to tensions between Chinese authorities and foreign missionaries. Despite these challenges, ancestor worship persisted due to its deep integration into Chinese culture.

Although ancestor worship has evolved over the centuries, it remains an integral part of Chinese culture. Today, rituals honoring ancestors are observed during traditional festivals such as Qingming and the Hungry Ghost Festival.