The Marduk Prophecy

The Marduk Prophecy is an ancient Mesopotamian text, written in Akkadian cuneiform, that narrates the travels of the statue of the god Marduk from Babylon and its eventual return. It is part of a broader genre of Mesopotamian prophetic literature, which often aimed to justify political and religious changes by linking them to divine will.

This prophecy was likely composed during the late second millennium BCE, possibly during the Kassite period or early first millennium BCE.

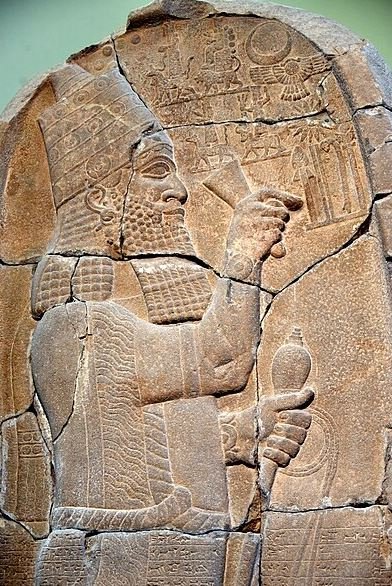

Illustration of Marduk, accompanied by his servant dragon Mušḫuššu.

The Text and Its Context

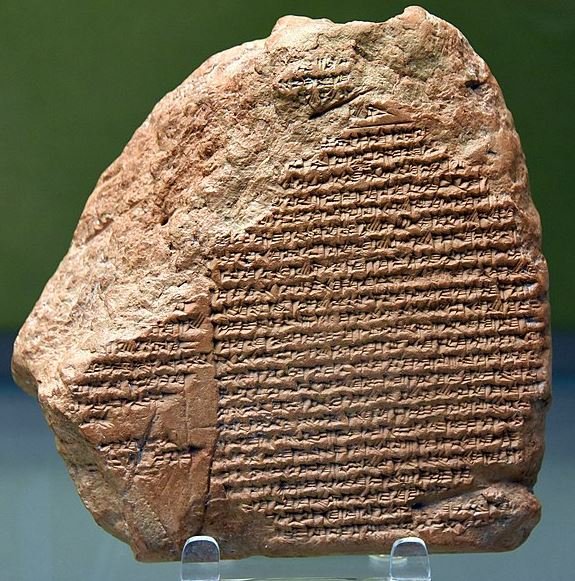

The prophecy survives on a fragmentary clay tablet, first discovered in the Library of Ashurbanipal (7th century BCE) in Nineveh. The original composition is much older, but later Assyrian kings saw value in preserving such texts. The prophecy is written in a poetic and prophetic style, resembling other Mesopotamian texts that project divine legitimacy onto rulers who restored important religious traditions.

The Marduk Prophecy is an Assyrian document dating between 714–613 BCE, discovered in the House of the Exorcist near a temple in Ashur.

This text follows a common ex eventu prophecy structure, meaning it was written after the events it describes but presents them as if they were predicted in advance. Such texts reinforced the idea that history was guided by divine will and that rulers who restored religious traditions were fulfilling divine prophecies.

Summary of the Narrative

The prophecy describes four key periods in which the statue of Marduk was removed from Babylon and taken to foreign lands. These episodes correspond to real historical events when Babylon fell under the control of external powers:

Elamite Invasion (12th century BCE)

The first event in the prophecy refers to the Elamites, who captured Babylon and took Marduk’s statue to their own territory. This corresponds to the historical invasion by Shutruk-Nakhunte, king of Elam, who sacked Babylon around 1158 BCE. The prophecy describes the suffering of the Babylonians and the misfortunes of the foreign rulers who took Marduk’s statue.

Kassite Rule and the Marduk Statue

The second episode may reflect the Kassite period (c. 1595–1155 BCE), when Babylon was under Kassite control.

The Kassites, originally foreigners from the Zagros Mountains, ruled Babylon for centuries and incorporated Marduk into their pantheon.

Although they honored Marduk, later Babylonian nationalistic texts, such as this prophecy, may have viewed them as outsiders and thus depicted their rule as illegitimate.

Assyrian Domination

The prophecy alludes to the Assyrians removing Marduk’s statue, likely referring to Tiglath-Pileser III (8th century BCE) or Sennacherib (7th century BCE).

Sennacherib, in particular, destroyed Babylon in the late 7th century BCE and removed Marduk’s statue.

The text portrays Assyria’s dominance as an act of impiety and suggests that the Assyrian kings suffered divine retribution.

The Return of Marduk

The final section celebrates the return of Marduk’s statue and the restoration of Babylonian power. This was historically realized when Esarhaddon (c. 681–669 BCE) or Nabonidus (556–539 BCE) restored Marduk’s cult in Babylon. The prophecy portrays this restoration as a divine fulfillment, ensuring Babylon’s rightful supremacy.

Religious and Political Significance

The Marduk Prophecy served several political and religious functions:

By portraying Marduk’s return as inevitable, the text reinforced the legitimacy of rulers who restored Babylon’s religious traditions. Kings such as Nebuchadnezzar I (12th century BCE) and Nabonidus (6th century BCE) could use this prophecy to justify their rule.

The Marduk Prophecy is not just a record of past events, but a reflection of how ancient civilizations understood their place in the world and sought divine legitimacy for their rulers.

The text criticizes foreign rulers who took Marduk’s statue, portraying them as doomed to failure. This reinforced Babylonian nationalism and the idea that Babylon was divinely chosen.

The prophecy presents a theological message: those who dishonor Marduk will suffer divine punishment. This reflected Mesopotamian beliefs that gods directly intervened in human history.

Connections to Other Mesopotamian Texts

The Marduk Prophecy shares themes with other Mesopotamian texts:

- The Enuma Elish (Babylonian Creation Epic): Establishes Marduk as the supreme deity.

- The Dynastic Prophecy: Another Babylonian text that justifies the rise and fall of dynasties based on divine will.

- The Nabonidus Chronicle: Records historical events surrounding the last Babylonian king, echoing the themes of divine favor and restoration.

Even though the Marduk Prophecy was written in antiquity, the themes of divine justice, national identity, and historical reinterpretation remain relevant.

Nabonidus Chronicle

Modern Scholarly Interpretations

Scholars view the Marduk Prophecy as both a historical document and a literary work.

The prophecy likely reflects real historical events but reinterprets them through a religious lens. It provides insight into Babylonian views on kingship, divine justice, and foreign rule.

It was possibly written to support a specific ruler, such as Nebuchadnezzar I or Nabonidus, by portraying them as divinely chosen restorers. Similar texts were used as propaganda to unify the population around a ruler’s legitimacy.

The prophecy emphasizes the centrality of Marduk in Babylonian religion. It reinforces the idea that Marduk, as the supreme god, controls the fate of nations.

Questions and Answers

Why was the Marduk Prophecy written?

It was likely composed during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar I (c. 1125–1104 BCE) as a propaganda piece celebrating his victory over the Elamites and the restoration of Marduk’s statue to Babylon.

How does the prophecy use historical events?

The author structured it as a prophetic vision, placing past events in a way that “predicts” the restoration of order by a Babylonian king. This technique aligns with Mesopotamian Naru Literature, which reinterpreted historical events for political or moral messages.

What is an example of a similar literary technique in Mesopotamian literature?

The Curse of Akkad reinterprets the reign of King Naram-Sin (c. 2262–2221 BCE), portraying him as impious to highlight the consequences of defying the gods.

What political themes are present in the Marduk Prophecy?

The text suggests that Marduk’s statue was content in Hatti and Assyria, which were Babylon’s allies, but dissatisfied in Elam, a traditional enemy. This reinforces Babylonian political perspectives.

Why was the removal of a deity’s statue significant?

Taking a deity’s statue from a conquered city symbolized the loss of divine protection. For Babylon, where Marduk was the supreme god, this was especially devastating.

Who was Marduk in Mesopotamian mythology?

Marduk was the son of Enki (Ea) and became the supreme deity after leading the younger gods in a battle against Tiamat, the primordial chaos goddess.

He defeated Tiamat, split her body to form the sky and earth, and created humans to help the gods maintain order in the universe.

A relief depicting Enki.

How did Marduk’s worship evolve over time?

His prominence grew during Hammurabi’s reign (1792–1750 BCE) and lasted until Persian rule (c. 485 BCE). Some scholars have noted that Marduk’s worship was almost monotheistic, though it never denied other gods.

READ MORE: Why was the Code of Hammurabi important?

Why was Marduk’s statue important to Babylon’s religious practices?

The Akitu Festival (New Year’s celebration) could not take place without his statue, as its absence symbolized divine abandonment, leading to chaos and disorder.

Marduk versus Tiamat

What were the consequences of Marduk’s absence, according to the prophecy?

The prophecy describes apocalyptic conditions, including starvation, fratricide, lawlessness, and natural disasters, reflecting the belief that Marduk’s absence brought calamity.

What happened to Marduk’s statue under Sennacherib’s rule?

Sennacherib sacked Babylon in 689 BCE and removed Marduk’s statue, an act seen as sacrilegious. His assassination in 681 BCE was later interpreted as divine punishment.

How did Esarhaddon attempt to restore Babylon?

Esarhaddon (681–669 BCE), Sennacherib’s successor, rebuilt Babylon, returned Marduk’s statue, and constructed an even grander temple, the ziggurat of Babylon.

The victory seal of Esarhaddon.

What were the major times Marduk’s statue was taken?

The statue was taken by Mursilli I of the Hittites (c. 1595 BCE), Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria (c. 1225 BCE), Shutruk-Nakhunte of Elam (c. 1150 BCE), Sennacherib (689 BCE), and finally destroyed by Xerxes I (c. 485 BCE).

What was the final fate of Marduk’s statue?

Greek historians Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus claim Xerxes I (also known as Xerxes the Great) destroyed Marduk’s statue after Babylon’s rebellion in 485 BCE. No later records mention it, supporting the theory that it was permanently lost.