Neferirkare Kakai: The Third Pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty

Neferirkare Kakai, the third pharaoh of Egypt’s Fifth Dynasty, lived during the mid-25th century BC. He was the son of Pharaoh Sahure and Queen Meretnebty, as confirmed by reliefs from Sahure’s causeway, which depict Neferirkare alongside his family members.

Initially named Ranefer, Neferirkare ascended the throne shortly after Sahure’s death. His rise to power marked a period of relative stability and familial continuity in the early Fifth Dynasty, with transitions of power occurring peacefully.

Pharaoh Sahure is often regarded as the father of Pharaoh Neferirkare Kakai. Image: Head of a gneiss statue of Sahure in gallery 103 of the New York Metropolitan Museum of ArtNeferirkare married Khentkaus II, who bore him two significant successors: Neferefre and Nyuserre Ini. Both played crucial roles in continuing their father’s legacy and completing some of his unfinished projects.

Pharaoh Sahure is often regarded as the father of Pharaoh Neferirkare Kakai. Image: Head of a gneiss statue of Sahure in gallery 103 of the New York Metropolitan Museum of ArtNeferirkare married Khentkaus II, who bore him two significant successors: Neferefre and Nyuserre Ini. Both played crucial roles in continuing their father’s legacy and completing some of his unfinished projects.

In addition to his documented children, some evidence suggests he may have fathered other offspring, including Prince Iryenre and possibly Queen Khentkaus III. These familial ties underscore Neferirkare’s dynastic importance and his role in consolidating the lineage of the Fifth Dynasty.

Neferirkare was the son of Sahure and Meretnebty. He married Khentkaus II, who bore his successors, Neferefre and Nyuserre Ini, both of whom contributed to continuing his legacy. Image: A statue of Neferefre, Neferirkare’s eldest son, was discovered by Paule Posener-Kriéger.

Reign Overview

Neferirkare’s reign lasted approximately 10–11 years, as determined by archaeological evidence such as cattle count records on the Palermo Stone. Though earlier sources like Manetho’s Aegyptiaca attributed a reign of 20 years to him, modern scholars consider this an overestimate. The brevity of his rule, coupled with his untimely death, left many of his grand construction projects incomplete.

Despite his short reign, Neferirkare significantly influenced Egyptian administration, religious practices, and architecture. His leadership also saw the continuation of trade relations with Nubia and possibly Byblos, highlighting Egypt’s expanding international connections during the Fifth Dynasty.

Architectural Achievements of Neferirkare

Neferirkare began constructing a pyramid at Abusir, initially planned as a step pyramid but later modified into a true pyramid, making it the largest of the Fifth Dynasty. Image: The pyramid of Neferirkare Kakai

The Pyramid Complex at Abusir

Neferirkare began constructing a pyramid at Abusir, initially planned as a step pyramid—a design not seen since the Third Dynasty. The project was later modified to become a true pyramid, the largest of the Fifth Dynasty. Unfortunately, Neferirkare’s death left the pyramid incomplete. His successor, Nyuserre Ini, made efforts to finish parts of the mortuary complex but relied heavily on mudbrick and wood due to resource constraints.

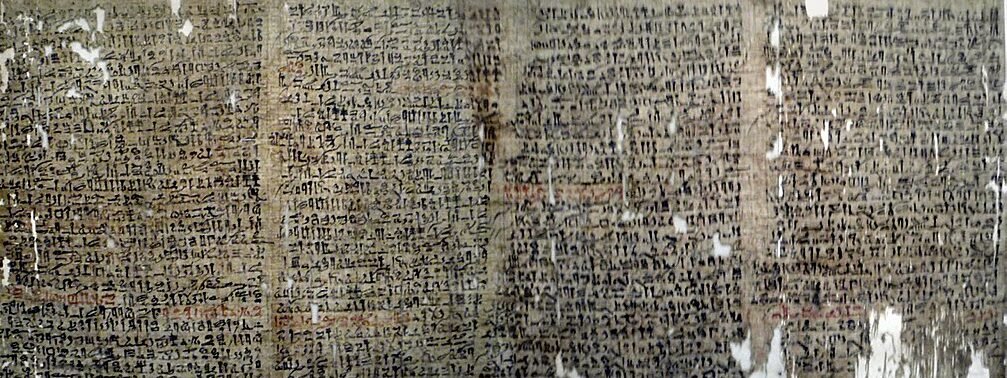

The Abusir papyri, discovered in his mortuary temple, provide invaluable insights into temple administration and daily operations. These documents, preserved because of the temple’s isolation, reveal the intricacies of managing royal cults and temple estates. Surrounding Neferirkare’s pyramid are smaller pyramids and tombs of family members, emphasizing the interconnectedness of royal burials during this period.

The Sun Temple: Setibre

Neferirkare also commissioned a sun temple dedicated to Ra, named Setibre, meaning “Site of the Heart of Ra.” Ancient texts describe this temple as the largest and most significant of its kind during the Fifth Dynasty. Although it remains undiscovered, records suggest it featured an obelisk, an altar, and other key elements central to the solar cult. The temple played a vital role in the distribution of offerings, reinforcing the king’s dependence on Ra for sustenance in the afterlife.

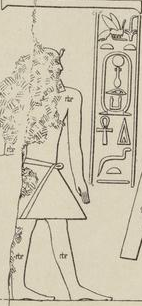

Neferirkare introduced the “Son of Ra” titulary, emphasizing the pharaoh’s divine connection to Ra. This reform became a standard element of royal titulary in subsequent dynasties. Image: Popular depiction of Ra, the Sun God

Religious and Administrative Innovations

One of Neferirkare’s most enduring contributions was the modification of the royal titulary. He separated the prenomen (throne name) and nomen (birth name) and associated them with the titles “King of Upper and Lower Egypt” and “Son of Ra,” respectively. This innovation emphasized the divine authority of the pharaoh and became a standard practice in subsequent dynasties. By systematically including the “Son of Ra” epithet, Neferirkare strengthened the ideological connection between the ruler and the sun god Ra.

Under Neferirkare’s rule, the priesthood and administration expanded, granting officials more autonomy and wealth. This period saw the construction of increasingly elaborate mastabas, featuring multiple rooms, family tomb complexes, and biographical inscriptions. These developments reflect a shift in elite culture, with officials beginning to record their achievements and roles in service to the king.

READ MORE: Sun god Ra’s journey through the underworld

Interactions with Officials

Neferirkare was remembered as a kind and benevolent ruler, as evidenced by inscriptions in the tombs of his contemporaries. An anecdote from Rawer’s tomb highlights the pharaoh’s compassion: during a ceremonial mishap where the king’s mace accidentally struck Rawer, Neferirkare pardoned the official and reassured him of his safety.

Similarly, when his vizier Washptah suffered a fatal stroke at court, Neferirkare ensured that the vizier received a dignified burial, complete with special endowments and rituals.

Known for his compassion, Neferirkare pardoned officials during ceremonial mishaps and ensured dignified burials for his courtiers.

These stories underline Neferirkare’s humanity and his ability to maintain strong relationships with his officials. His leadership style likely contributed to the stability and effectiveness of his administration.

Trade and External Relations

Trade flourished during Neferirkare’s reign, maintaining Egypt’s connections with Nubia and potentially extending to Byblos on the Levantine coast. Artifacts bearing his name, such as seal impressions found in the fortress of Buhen, confirm interactions with Nubia. Additionally, an alabaster vessel inscribed with his name, discovered in Byblos, suggests limited trade or diplomatic exchanges with the region.

While there is little evidence of military activity during his rule, the presence of prisoner statues in his mortuary temple has led some scholars to speculate about minor campaigns. However, these statues may have been symbolic rather than indicative of actual warfare, as similar figures were common in royal complexes of the period.

A reconstructed ritual vase of sycamore wood with faience and gold inlays featuring Neferirkare’s cartouche is displayed in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin.

Cultural Legacy and Funerary Cult

Neferirkare’s mortuary cult persisted beyond the Old Kingdom, though its influence diminished over time. Cylinder seals and other artifacts indicate that his cult was active during the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom, albeit on a smaller scale. Statues from this period include inscriptions invoking offerings for Neferirkare, demonstrating the enduring reverence for his reign.

The Papyrus Westcar, a Middle Kingdom text, mythologizes Neferirkare as a divine son of Ra and a mortal woman named Rededjet. This tale aligns with the ideological narrative of the Fifth Dynasty, which emphasized the divine origins of its kings. Such stories reflect how Neferirkare’s legacy was integrated into broader cultural and religious frameworks.

His funerary cult persisted into the Middle Kingdom, and stories like the Papyrus Westcar mythologize him as a benevolent ruler and divine offspring of Ra.

READ MORE: Most Famous Middle Kingdom Pharaohs and their Accomplishments

Challenges and Unfinished Projects

Neferirkare’s untimely death posed challenges for the completion of his ambitious construction projects. His pyramid at Abusir remained unfinished, and Nyuserre Ini redirected resources to complete the mortuary temple and other structures. The reliance on mudbrick and other cost-effective materials highlights the difficulties faced by his successors in balancing ongoing royal projects.

Neferirkare’s sun temple, Setibre, described as the most prominent of its time, remains undiscovered.

Similarly, the incomplete state of Setibre indicates that Neferirkare’s vision for the sun temple was not fully realized. These unfinished projects, however, underscore the scale of his ambitions and his commitment to reinforcing the solar cult.

Significance in Egyptian History

Neferirkare’s reign represents a turning point in the Fifth Dynasty, characterized by a blend of innovation, continuity, and expansion. His architectural projects, while incomplete, set new standards for pyramid and temple design. The administrative reforms initiated during his rule laid the groundwork for future expansions in governance and priesthood.

Neferirkare Kakai’s policies and projects significantly shaped the Fifth Dynasty’s identity, leaving a lasting imprint on Egyptian culture and governance.

His emphasis on the solar cult and the ideological connection between the pharaoh and Ra reinforced the centrality of religion in Egyptian society. By formalizing the royal titulary and integrating divine elements into his titles, Neferirkare elevated the symbolic status of the king, a practice that endured for centuries.

Conclusion

Neferirkare Kakai’s life and reign exemplify the complexities of pharaonic leadership during the Fifth Dynasty. His architectural endeavors, religious reforms, and administrative policies left a lasting imprint on ancient Egypt. His role as a compassionate leader, innovative reformer, and devout proponent of the solar cult highlights his significance in the broader narrative of Egypt’s Old Kingdom.

READ MORE: Major Events in the History of Ancient Egypt

Frequently Asked Questions about Neferirkare Kakai

Neferirkare Kakai was the third king of Egypt’s Fifth Dynasty, ruling during the early to mid-25th century BC. He succeeded his father, Sahure, and is noted for significant developments in administration, culture, and architecture. Image: Neferirkare Kakai, first shown as Prince Ranefer in Sahure’s complex, gained titles later.

What was Neferirkare’s name before he became king?

Before ascending the throne, Neferirkare was known as Ranefer A.

Who were Neferirkare’s parents?

Neferirkare was the son of Pharaoh Sahure and Queen Meretnebty.

How long did Neferirkare reign, and who succeeded him?

Neferirkare reigned for approximately 17 years. He was succeeded by his sons, first Neferefre and later Nyuserre Ini.

What qualities defined Neferirkare’s rule?

Neferirkare was known as a benevolent and compassionate ruler, advocating for his courtiers and fostering growth in Egypt’s administrative and priestly systems.

What architectural advancements occurred during Neferirkare’s reign?

His reign saw the construction of more elaborate mastabas by officials, featuring biographical inscriptions for the first time, reflecting advancements in architecture and record-keeping.

Personified agricultural estate of Neferirkare depicted in the tomb of Sekhemnefer III.

What was his contribution to the royal titulary?

Neferirkare reformed the royal titulary by distinguishing the nomen (birth name) from the prenomen (throne name). He introduced the practice of enclosing the nomen in a cartouche and preceding it with the epithet “Son of Ra.”

What were Neferirkare’s contributions to trade?

Neferirkare maintained trade relations with Nubia to the south and likely with Byblos on the Levantine coast, enhancing Egypt’s economic and cultural connections.

What pyramid project did Neferirkare initiate?

Neferirkare began constructing a pyramid at Abusir called Ba-Neferirkare (“Neferirkare is a Ba”). Initially planned as a step pyramid, it was later modified into a true pyramid but remained incomplete due to his death.

What was the significance of Neferirkare’s sun temple?

Neferirkare built a sun temple named Setibre (“Site of the heart of Ra”), described in ancient texts as the largest of its kind during the Fifth Dynasty. Its location has not yet been discovered.

What sources document Neferirkare’s reign and position in the royal lineage?

Neferirkare’s reign is recorded in contemporary inscriptions, such as those in the tombs of vizier Washptah and courtier Rawer, as well as in the Abydos King List and the Saqqara Tablet. These sources confirm his position between Sahure and Neferefre, though discrepancies in the Turin Canon have led to debates about his reign length.

A relief fragment from Sahure’s mortuary temple depicts him with his sons, later updating Neferirkare’s portrayal.

How was Neferirkare venerated after his death?

A funerary cult honoring Neferirkare operated in his mortuary temple, completed by his son Nyuserre Ini. The cult persisted until the end of the Old Kingdom and may have been briefly revived in the Middle Kingdom.

What is the “Papyrus Westcar,” and how does it relate to Neferirkare?

The “Papyrus Westcar” is a Middle Kingdom tale that mythologically depicts Neferirkare as a son of the sun god Ra and a woman named Rededjet, along with Userkaf and Sahure. This story illustrates the dynastic belief in the divine origins of pharaohs.