Sed Festival in Ancient Egypt

The Sed festival (ḥb-sd), or Feast of the Tail, was an ancient Egyptian ceremony celebrating a pharaoh’s continued rule, typically after 30 years and then every 3–4 years.

The name of Sed Festival references Wepwawet, the wolf god, and the animal tail worn by early pharaohs. This symbolizes authority. Image: King Djoser running for the Heb-Sed celebration

Origin Story of the Sed Festival

The Sed Festival, also known as Heb Sed, originated in the earliest periods of ancient Egyptian history as a jubilee celebration to reaffirm the pharaoh’s divine authority and physical vitality. Its name is derived from the Egyptian wolf god Wepwawet, also called Sed, symbolizing strength and guidance.

Originating as a possible alternative to ritually replacing aging rulers, the Sed festival reinforced pharaonic power and state ideology.

The festival likely evolved as a means to ensure the ruler’s continued capacity to govern effectively, replacing earlier practices that may have included ritually replacing aging or ineffective leaders.

Over time, it became a formalized event, deeply rooted in religious, political, and ceremonial traditions. By connecting the king to divine powers, the festival played a critical role in maintaining the perceived unity and stability of Egypt.

READ MORE: Most Famous Ancient Egyptian Pharaohs and their Accomplishments

History of the Sed Festival

Alabaster sculpture of Pharaoh Pepi I celebrating Heb Sed, c. 2362 BCE, Brooklyn Museum.

Early Dynastic Period

The Sed Festival’s earliest documented celebrations date back to the First Dynasty, during the reign of King Den. Evidence such as inscriptions and objects indicate that Den partook in this festival to symbolize his continued dominion over Egypt. These early iterations of the festival focused on the pharaoh’s physical endurance and ability to perform ritualistic acts, reflecting his divine fitness to rule.

Ebony label detail of Pharaoh Den running boundary markers in the Sed festival ritual.

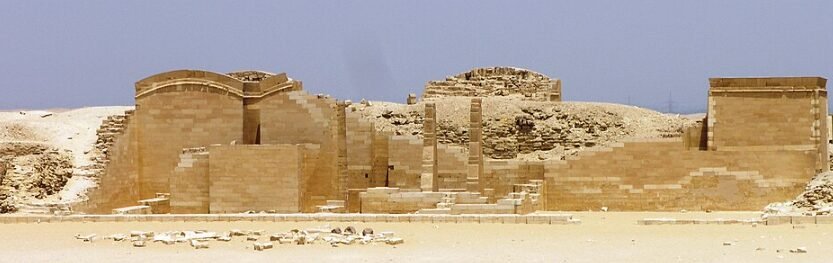

Pharaoh Djoser of the Third Dynasty further institutionalized the Sed Festival. His mortuary complex at Saqqara, including the boundary stones in the Heb Sed court, reflects how the festival became intertwined with notions of eternal kingship. Depictions of Djoser performing the Heb Sed in the false doorway of his pyramid highlight the belief that the king could carry out the ceremony perpetually in the afterlife, ensuring his eternal authority.

Old Kingdom

During the Old Kingdom, the festival became a well-established tradition for rulers who had reigned for thirty years. Pharaoh Pepi I of the Sixth Dynasty is a notable example, as alabaster containers and inscriptions on the South Saqqara Stone document his jubilee. This period also marks the last reliable evidence of Sed Festivals before the First Intermediate Period, a time of political fragmentation and diminished central authority.

Middle Kingdom Revival

The Middle Kingdom, characterized by the reunification of Egypt under powerful pharaohs, witnessed the revival of the Sed Festival.

Pharaohs such as Senusret I and Amenemhat I reintroduced the celebration, integrating it into their political and religious reforms. Senusret I notably held his jubilee in his 31st regnal year and constructed the White Chapel at Karnak to commemorate the event. This structure, intricately decorated with scenes of his Sed Festival, served as a lasting testament to his divine authority and the restored stability of the Egyptian state.

Interestingly, not all pharaohs adhered strictly to the thirty-year rule. Amenemhat II, despite a reign of approximately 35 years, left no evidence of a Sed Festival, suggesting variations in its observance depending on political and personal circumstances.

New Kingdom Splendor

The New Kingdom saw some of the most elaborate Sed Festivals in Egyptian history. Pharaoh Amenhotep III celebrated multiple jubilees, with inscriptions and monuments showcasing the grandeur of his reign. Ramesses II (i.e. Ramses the Great), known for his extraordinary longevity, held over a dozen Sed Festivals, each reinforcing his divine kingship and unparalleled power.

Hatshepsut, one of the few female pharaohs, adapted the tradition to suit her unique position. She celebrated her jubilee by including years she served as co-ruler with her husband, Thutmose II. This approach allowed her to emphasize her legitimacy as a ruler and her divine mandate, which she claimed was inherited from her father, Thutmose I.

Akhenaten, another notable New Kingdom ruler, broke with tradition by celebrating a Sed Festival in his third regnal year. This early jubilee aligned with his radical religious reforms, including the establishment of Aten as the sole deity and the relocation of Egypt’s capital to Amarna. For Akhenaten, the Sed Festival became a means to consolidate religious and political power, showcasing his role as a divine intermediary.

Her husband and her reigns were turbulent times in Egyptian history. The royal couple had tossed the old gods, primarily based in Thebes, and established a somewhat new religion with the sun god Aten at the top of the pyramid. This incurred the displeasure of many Theban priests and religious leaders. Image: Akhenaten and Nefertiti. Louvre Museum, Paris.

Third Intermediate Period

During the Third Intermediate Period, the Sed Festival continued under the Libyan kings who ruled Egypt. Shoshenq III, Shoshenq V, and Osorkon II all celebrated jubilees, despite the decline in centralized power. Osorkon II, in particular, marked his Heb Sed with grandeur by constructing a temple at Bubastis adorned with scenes of the festival. This era demonstrates how the tradition persisted even during periods of political fragmentation, underscoring its enduring significance in Egyptian culture.

Key records of the Sed Festival in ancient Egypt come from Neuserra, Akhenaten, and Osorkon II’s reigns.

Significance of the Sed Festival

The Sed Festival featured temple rituals, processions, offerings, and the symbolic raising of the djed, a phallic emblem of strength and longevity. The event also reaffirmed dominion over Upper and Lower Egypt. Image: Heb-Sed court, south of Pyramid of Djoser in Saqqara, Egypt

Reinforcement of Divine Authority

At its core, the Sed Festival served to reaffirm the pharaoh’s role as the divine representative of the gods on Earth. By performing rituals that symbolized physical endurance and spiritual devotion, the king demonstrated his continued fitness to rule. The festival often included the raising of the djed, a symbol of stability and longevity, and ceremonies emphasizing the pharaoh’s connection to the gods. This divine endorsement was critical in legitimizing the ruler’s authority.

Unity of Upper and Lower Egypt

One of the central themes of the Sed Festival was the reaffirmation of the pharaoh’s control over Upper and Lower Egypt. Rituals often included symbolic boundary markers, representing the unification of the two regions. By participating in these ceremonies, the king renewed the bond between the state and the divine, ensuring harmony and prosperity for the kingdom.

Ritual and Celebration

The festival was an elaborate event involving processions, offerings, and temple rituals. It often featured the pharaoh running a symbolic course to demonstrate his physical vitality and competence. These acts not only reinforced the ruler’s image as a strong and capable leader but also connected the people to the divine aspects of kingship through grand public spectacles.

Mortuary and Afterlife Implications

The inclusion of Sed Festival imagery and symbols in mortuary complexes, such as Djoser’s pyramid, highlights its significance in the afterlife. By depicting the pharaoh performing the jubilee rituals, these monuments ensured the eternal continuation of the festival, symbolizing unending dominion and stability even after death.

Political Stability and Continuity

The Sed Festival was more than a religious or ceremonial occasion; it was a political tool that reinforced the central authority of the pharaoh. In times of unrest or transition, such as the Middle Kingdom or during Akhenaten’s religious reforms, the festival was used to unify the nation and reassert the legitimacy of the ruling dynasty.

Adaptability Across Eras

One of the festival’s remarkable features was its adaptability. From the Old Kingdom to the Third Intermediate Period, pharaohs tailored the celebration to their needs and circumstances. For example, Hatshepsut modified the traditional timeline to suit her unique claim to power, while Akhenaten used it as a platform for his revolutionary religious agenda. This flexibility ensured the festival’s persistence throughout Egypt’s long history.

Conclusion

The Sed Festival was one of ancient Egypt’s most enduring traditions, symbolizing the eternal vitality and divine authority of the pharaoh. From its origins in the Early Dynastic Period to its adaptation during the Third Intermediate Period, the festival reflected the political, religious, and social dynamics of Egyptian society. It was a celebration of unity, a reaffirmation of divine kingship, and a testament to the enduring power of ritual in maintaining order and legitimacy.

Frequently Asked Questions

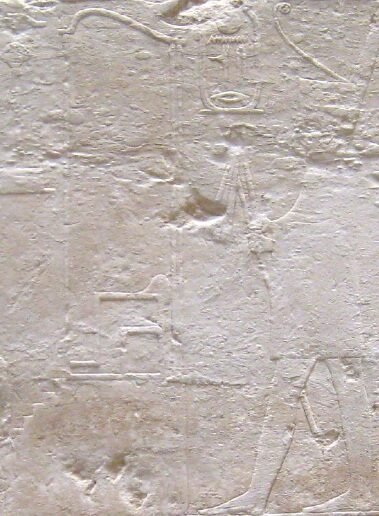

Whether through grand architectural projects like Djoser’s pyramid complex or the lavish jubilees of Ramesses II, the Sed Festival left an indelible mark on the cultural and political landscape of ancient Egypt. Image: Limestone relief fragment depicts an unidentified pharaoh in Heb Sed robe, white crown, and menat, 12th Dynasty, Koptos, Egypt, Petrie Museum.

What was the purpose of the Sed festival?

To reaffirm the pharaoh’s authority and divine role as ruler of Egypt.

Which early pharaohs celebrated the Sed festival?

Den of the First Dynasty and Djoser of the Third Dynasty.

How did Djoser commemorate his Sed festival?

Through boundary stones and depictions in his pyramid complex symbolizing his eternal dominion.

What evidence exists of Pepi I’s Sed festival?

Inscriptions on the South Saqqara Stone and alabaster containers commemorating his jubilee.

Cartouches of Pepi I and Pyramid Texts

Why is there no evidence of Sed festivals from the First Intermediate Period?

The decline in centralized state activities likely caused the absence of evidence.

How did the Middle Kingdom restore the tradition of the Sed festival?

Pharaohs like Senusret I celebrated jubilees, with Senusret commemorating his in the White Chapel at Karnak.

Which New Kingdom pharaohs are notable for their Sed festivals?

Amenhotep III and Ramesses II, with Ramesses celebrating more than a dozen jubilees.

Relief of Pharaoh Nyuserre celebrating his Sed festival

How did Hatshepsut adapt the Sed festival?

She counted her years as consort and co-ruler to celebrate her jubilee, possibly tied to her father Thutmose I’s death.

What is significant about Osorkon II’s Heb Sed festival during the Third Intermediate Period?

He celebrated with grandeur, constructing a temple at Bubastis decorated with festival depictions.