What triggered the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)?

The Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) pitted the declining Ottoman Empire against an alliance led by the Russian Empire, joined by Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro.

Summary

The Russo-Turkish War reshaped the Balkans, ended five centuries of Ottoman rule in parts of Southeastern Europe, and influenced European diplomacy for decades to come.

Each side’s motivations and fears were influenced by recent history, ongoing nationalist uprisings, religious tensions, and shifting balances of power.

In the end, Russia and its allies prevailed, altering the map of Europe and setting the stage for new states to emerge in the Balkan peninsula.

“Battle of Shipka Pass”, one of the major battles during the Russo-Turkish War.

READ MORE: 10 Greatest Ottoman Sultans and their Accomplishments

Motives and Aims

Following the Crimean War (1853–1856), Russia sought to recover from a humiliating defeat that had forced it to dismantle its Black Sea Fleet and fortifications. This loss still weighed on Russian policy, prompting a desire for strategic and territorial gains, including the re-establishment of its influence in the Black Sea region.

Meanwhile, many Balkan communities—such as Bulgarians, Serbs, and Montenegrins—were restive under Ottoman rule, complaining of religious discrimination and economic exploitation.

Russia, propelled by Pan-Slavic sentiment, cast itself as the protector of Orthodox Christians in the Balkans. The Ottomans, on the other hand, hoped to stifle nationalist revolts and reform their empire from within, though ongoing internal crises and heavy debts hindered these efforts.

Prelude to the Russo-Turkish War

After the Crimean War, the 1856 Paris Peace Treaty mandated that the Ottoman authorities grant non-Muslim subjects equal rights with Muslims. Although the Ottoman government issued edicts to comply, progress was inconsistent. Many Christian communities believed these promises remained largely unfulfilled, fueling discontent.

Lebanon erupted in violence when Maronite Christian peasants revolted against Druze feudal lords. An Ottoman envoy took steps to restore order, but the unrest led to European intervention, with France and Britain dispatching forces to prevent unilateral gains by either power. This event underscored the fragility of Ottoman authority and heightened European interest in Ottoman affairs.

Discontent also spread in Crete, where Greek-speaking Christian communities demanded union with Greece. Insurgents controlled vast rural areas, while Ottoman garrisons remained in fortified cities. Though the Ottomans eventually suppressed the uprising, harsh tactics and reports of civilian massacres triggered outcry in Europe, fueling anti-Ottoman sentiments.

Mounting nationalist fervor in Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Bulgaria prompted uprisings aimed at securing autonomy. In Bulgaria, the April Uprising of 1876 was harshly suppressed by Ottoman regulars and irregulars, leading to thousands of deaths and mass destruction of villages. These atrocities became widely publicized in Europe through journalist reports, causing a wave of sympathy for the rebels.

Changing Dynamics in Europe

Despite being on the victors’ side in the Crimean War, the Ottoman Empire continued to weaken financially and militarily. Pressure to modernize strained the state’s budget, forcing reliance on steep foreign loans. At the same time, repeated efforts to quell unrest across far-flung territories indicated the empire was struggling to keep pace with nationalist movements.

The Concert of Europe, meant to preserve equilibrium among major states, was shaken by Italy’s unification wars and shattered by Germany’s rise after 1870. Russia, seeking allies, found common ground with Prussia (soon to be Germany).

Austria-Hungary, wary of Russian expansion, maneuvered diplomatically to claim territory in the Balkans if the Ottoman Empire collapsed. Britain and France balanced conflicting aims, supporting Ottoman integrity in principle while also condemning reported abuses against Christian subjects.

Diplomatic Maneuvering and Escalation

Russia had to be certain that any conflict with the Ottomans would not draw the other great powers into an anti-Russian coalition. Agreements with Austria-Hungary at Reichstadt (1876) assured that Vienna would remain neutral in exchange for territorial considerations in the Balkans. Meanwhile, widespread outrage in Russia over the Bulgarian massacres created domestic pressure for action.

The Constantinople Conference (1876) attempted a peaceful resolution by proposing autonomy for several Balkan provinces but was rejected by the Ottoman leadership, which insisted on retaining sovereignty. By 1877, convinced that diplomatic solutions had failed, Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire.

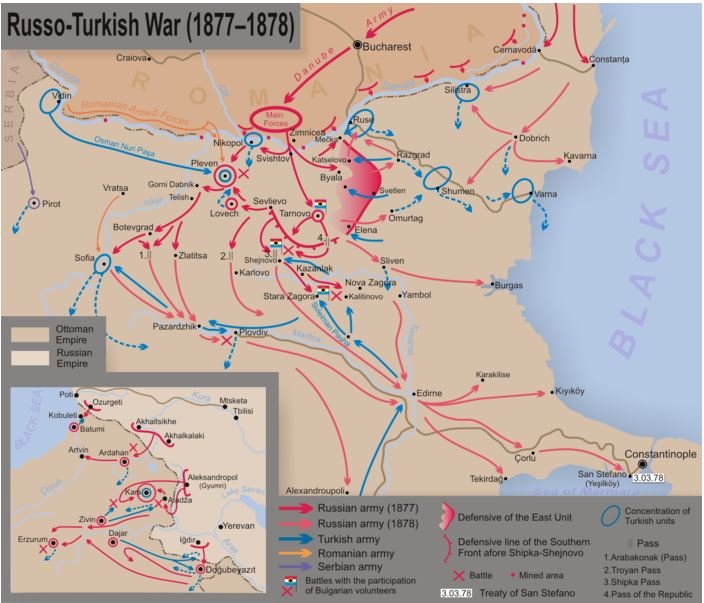

A map depicting key movements and activities during the war.

Outbreak of War and Early Battles

Russia’s main army of roughly 185,000 men crossed the Danube with Romanian permission in June 1877. Ottoman forces, heavily outnumbered, relied on fortified strongholds and the advantage of defending interior lines. However, command errors and limited reinforcements weakened the Ottoman strategic position. Romania, declaring independence, joined Russia in besieging Ottoman fortresses along the Danube.

A pivotal episode unfolded at Plevna, where Ottoman commander Osman Nuri Pasha’s skillful defense inflicted severe losses on the Russian invaders. Two failed Russian assaults revealed the Ottomans’ superior repeating rifles and entrenchment tactics. Only after Romanian troops reinforced the Russians, and the combined forces completely surrounded Plevna, did Osman Pasha attempt a breakout, ultimately surrendering in December 1877. This defeat removed the main barrier to Russian advance south.

Bulgarian volunteers, motivated by decades of repressive Ottoman policies, fought alongside the Russians, contributing local knowledge and enthusiasm. Serbian forces, emboldened by Russian progress, again declared war on the Ottomans, capturing important towns in the southern regions. The war, marked by continuous fighting throughout the Balkans, revealed the Ottomans’ inability to halt multiple offensives once their principal defense lines fell.

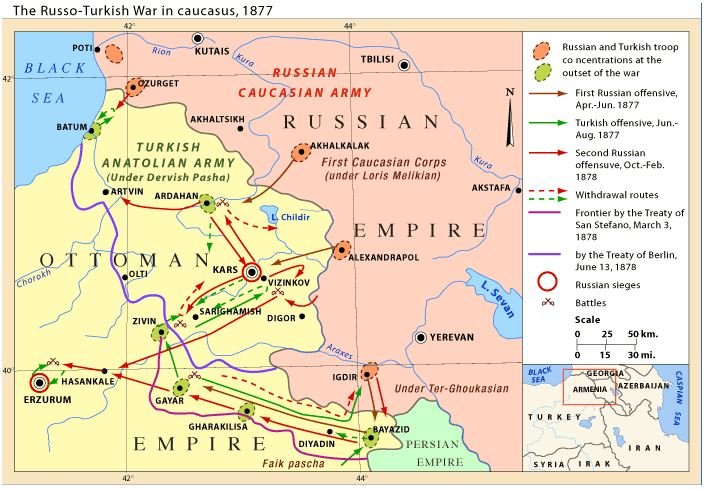

Caucasian Front

While the main focus was on the Balkans, fierce fighting also took place in the Caucasus. Russian forces, led by experienced Armenian generals, seized Ottoman positions around Kars and Bayazid.

Though the Ottomans possessed modern Krupp artillery, they were spread thin, and the Russians managed to push forward, eventually capturing key fortresses like Kars in November 1877. With the approach of winter, and Ottoman supply lines stretched, the Russians secured the mountainous regions of Ardahan and Batum, furthering their territorial aims.

Aftermath and Agreements

Treaty of San Stefano

In early 1878, Russian forces marched close to Constantinople, prompting Britain to dispatch afleet to deter further Russian advances. Under pressure, the Ottomans offered a truce, and the subsequent Treaty of San Stefano recognized the independence of Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro, while creating a large autonomous Bulgaria. This arrangement alarmed Austria-Hungary and Britain, who feared a powerful Russian ally in Southeastern Europe.

Congress of Berlin

The Great Powers convened at the Congress of Berlin (1878) and significantly revised the Treaty of San Stefano. Bulgaria was split into a smaller principality in the north and an autonomous province of Eastern Rumelia in the south, returning other Bulgarian-populated regions to direct Ottoman rule. Bosnia and Herzegovina was placed under Austro-Hungarian administration, underscoring the expansion of Habsburg influence. Though Russia kept its acquisitions in the Caucasus—Kars, Ardahan, and Batum—the final settlement limited its gains in the Balkans.

Anton von Werner’s 1881 painting, “Congress of Berlin”, portrays the final meeting held at the Reich Chancellery on July 13, 1878.

Impact on Local Populations

The war unleashed massive population shifts. Many Muslims fled from newly formed or expanded Christian states, and some Christian communities were displaced as battles raged. Both sides committed atrocities that devastated civilians, reflecting the harshness of nineteenth-century warfare. Though Bulgaria gained autonomy, many ethnic Bulgarians in Macedonia had to wait for future conflicts to achieve national unification. The ongoing tension in the region, combined with European rivalry, foreshadowed future Balkan crises.

Long-Term Consequences

The war accelerated the end of direct Ottoman authority in large parts of Southeastern Europe. Serbia, Romania, and Montenegro gained formal independence, while Bulgaria, supported by Russia, became an autonomous principality. These shifts reshaped the political map of the Balkans. Over the following decades, further uprisings and wars occurred, as national aspirations remained unfulfilled in many multiethnic areas.

Russia’s victory stirred suspicions among the other powers and heightened the rivalry between Russia and Austria-Hungary, both of which vied for dominance in the Balkans. Britain, too, became more vigilant in containing what it perceived as Russian expansion toward the Mediterranean. Bismarck’s Germany took a mediating role but found itself increasingly caught between competing alliances in Europe.

The Ottoman Empire grew more economically fragile due to war debts and the administrative costs of relocating Muslim refugees expelled from former Ottoman lands. Although reforms were proposed in the aftermath, they never fully quelled discontent in the empire’s remaining Balkan and Middle Eastern provinces. This outcome amplified future nationalist movements, weakening the empire further.

During this war, the Ottoman authorities adopted the Red Crescent instead of the Red Cross to mark military medical personnel, citing the cross’s association with past Crusades. This decision later became permanent for many Muslim countries and marked a significant branch in the symbols of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

Questions and Answers

A depiction of the Siege of Plevna 1877, a significant event during the war.

What were the main causes of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878?

Russia aimed to regain territory lost during the Crimean War, restore its influence in the Black Sea, and champion Balkan nationalism against Ottoman rule.

Who fought in the war?

The principal combatants were the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire. Russia was joined by Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro; volunteers from Bulgaria also fought alongside the Russians.

Why did the treatment of Christians in the Ottoman Empire spark international concern?

Despite promises of equal rights, massacres in places like Lebanon, Crete, and Bulgaria revealed continuing oppression. News of atrocities, especially against Balkan Christians, galvanized public opinion in Europe and Russia.

What role did the Great Powers of Europe play?

Britain, Austria-Hungary, France, and Germany were wary of Russian expansion. Their diplomatic pressure—culminating in agreements like the Congress of Berlin—ultimately reshaped Ottoman territories to keep a balance of power.

How did the war unfold in the Balkan theater?

Russian and Romanian armies crossed the Danube and besieged Ottoman fortresses like Plevna. After intense battles, including the defense of Shipka Pass, they pushed Ottoman forces close to Constantinople.

What was the outcome for the Balkan states?

Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro formalized their independence; Bulgaria became an autonomous principality, ending nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule.

How did the conflict affect the Caucasus region?

Russia captured key Ottoman strongholds such as Kars and Batum. This expanded Russian territory in the Caucasus but also displaced large Muslim populations who fled into Ottoman lands.

Map highlighting the The Russo-Turkish War in Caucasia.

What were the broader consequences of the war?

It altered the map of Southeastern Europe, weakened the Ottoman Empire, and fueled nationalist movements. The Great Powers forced revisions to Russia’s territorial gains through the Congress of Berlin, shaping a new—and often tense—Balkan order.