Origins and Practice of Magic in Ancient Greece

Magic in Ancient Greece was a complex and multifaceted aspect of cultural and spiritual life, blending religious practices, folklore, and early natural philosophy

Origins of Magic in Ancient Greece

The roots of magic in Ancient Greece lie in the interplay between mythological traditions, religious practices, and interactions with neighboring cultures such as Egypt and Mesopotamia. The Greek term for magic, “mageia,” derived from the Persian word for priests, “magi,” highlights its foreign connotations. By the time of Classical Greece (5th–4th centuries BCE), magic was associated with both divine favor and nefarious manipulation of the natural world.

Connection to Mythology

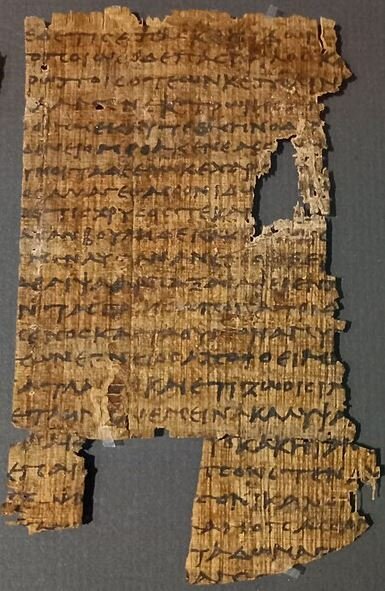

A manuscript of Homer’s Odyssey.

Magic appeared frequently in Greek myths. Figures like Circe and Medea exemplified the dual nature of magic as both wondrous and dangerous. Circe, the enchantress from ancient Greek poet Homer’s Odyssey, was renowned for her ability to transform men into animals. Medea, a sorceress in Euripides’ Medea, used her magical knowledge to aid Jason in acquiring the Golden Fleece but also employed it for vengeance.

Roles of Magic in Society

Magic in ancient Greece fulfilled multiple societal roles:

Magic was often intertwined with religious rituals. For example, individuals performed apotropaic rites (intended to ward off evil) to protect themselves from malevolent spirits or curses. Amulets and charms were commonly used in such contexts.

Healing practices in ancient Greece often combined natural remedies with magical incantations. Some practitioners, like Hippocrates, began separating natural medicine from superstition, but many healing rituals retained mystical elements.

Magic in Ancient Greece was a multifaceted phenomenon, encompassing religious rituals, healing practices, and supernatural beliefs.

Protective magic aimed to shield individuals or properties. Binding spells (katadesmoi) were widely used in both personal and professional rivalries, inscribed on lead tablets and buried to invoke divine intervention.

Erotic magic was prevalent, particularly among those seeking to attract or compel the affections of others. Spells, potions, and amulets were popular tools in this domain.

Magic often intersected with divination, as seen in oracular sites like Delphi. Practitioners sought to interpret divine will or predict future events through methods such as dream interpretation, astrology, and the casting of lots.

Philosophical Interpretations of Magic

Ancient Greek philosophers exhibited diverse attitudes toward magic, ranging from skepticism to fascination. These attitudes helped shape broader cultural perspectives on its legitimacy.

Ancient Greek philosopher Plato acknowledged the existence of magical practices but was critical of their misuse. He condemned those who exploited magic for personal gain, yet he saw a place for rituals that aligned with divine harmony.

Also, Aristotle approached magic with a rationalist perspective, attempting to demystify its phenomena through natural explanations. For example, he attributed certain magical effects to psychological manipulation or natural forces.

Stoic philosophers viewed the universe as governed by divine reason (logos). They often dismissed magic as superstition unless it adhered to natural laws.

Techniques and Practices

Magic in Ancient Greece relied on a variety of techniques and tools, often blending symbolic gestures with invocations of divine or supernatural powers.

Incantations and Spells

Spoken or written formulas were central to magical rituals. These often invoked deities, spirits, or cosmic forces to achieve specific outcomes.

Binding Spells (Katadesmoi)

These spells sought to constrain or compel others, often involving lead tablets inscribed with curses and buried in locations thought to be close to the underworld, such as graves.

Amulets and Talismans

Objects imbued with protective or healing powers were common. Materials like stones, metals, and animal parts were selected for their symbolic properties.

Potions and Herbs

Herbal knowledge was integral to magical practices. Plants like mandrake, henbane, and hellebore were associated with both medicinal and mystical properties.

Necromancy

The practice of communicating with the dead, necromancy, was a prominent aspect of Greek magic. Practitioners sought guidance or knowledge from the deceased, often through elaborate rituals.

Astrology

Although not as developed as later Hellenistic astrology, early Greek practices included celestial observation for predicting events or understanding divine will.

Greatest Scientists of the Hellenistic Period and their Accomplishments

Practitioners of Magic

In Greek society, the practitioners of magic ranged from respected religious figures to marginalized individuals:

Some magicians were connected to religious institutions or cults, acting as intermediaries between the divine and mortal worlds.

There were also healers and herbologists. These individuals were skilled in the medicinal use of herbs. Their activities often blurred the lines between science and magic.

Witches and sorcerers like Circe and Medea influenced societal perceptions of witches as powerful yet dangerous individuals.

“Circe Offering the Cup to Ulysses”, artwork by English artist John William Waterhouse.

Magic was deeply integrated into Greek culture and daily life, influencing myths, practices, and personal beliefs.

In ancient Greece, traveling magicians often performed for audiences or provided services, including love spells and curse removals.

Women were often linked to magic, both as practitioners and as scapegoats for societal anxieties. Their roles varied from revered priestesses to feared witches.

Magic and the Law

Magic occupied an ambiguous legal status in Ancient Greece. While it was not uniformly outlawed, certain practices, particularly harmful ones, were prosecuted.

Socrates’ trial in 399 BCE reflects societal concerns about unconventional spiritual practices. While not directly accused of magic, he was charged with corrupting the youth and introducing new gods, accusations tied to magical connotations.

Greek city-states often legislated against practices like poisoning or harmful curses, which could fall under the category of magic.

Magic in Hellenistic and Roman Periods

During the Hellenistic period (323–31 BCE), magic in Greek culture became more systematized, influenced by Egyptian and Babylonian traditions.

The Greek Magical Papyri, a collection of texts from the Hellenistic and Roman periods, provides detailed insights into magical practices, including spells, rituals, and incantations.

The integration of Babylonian astrology and Egyptian Hermeticism enriched Greek magical traditions. These systems emphasized the interconnectedness of the cosmos and human destiny.

The blending of Greek, Egyptian, and other traditions during this era led to the development of new magical systems, often incorporating foreign deities and symbols.

Critiques and Decline

As Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire, attitudes toward magic shifted. Early Christian writers condemned magic as pagan and diabolical, leading to its decline in mainstream Greek culture.

Church leaders like Augustine framed magic as heretical, associating it with demonic influence.

Despite official opposition, elements of Greek magic persisted in folk traditions and rural practices.

Questions and answers about the Magic in Ancient Greece

Circe transforming Ulysses’ followers back into their human forms. Painting by Italian painter Giovanni Battista Trotti.

Who practiced magic in ancient Greece?

Magicians, referred to as magoi—originally linked to Persian priests—were the practitioners of magic. They were seen as custodians of secret knowledge and skilled in fields like mathematics and chemistry. These figures were both revered and feared, often living on the fringes of society.

How was magic represented in Greek mythology?

Magic played a prominent role in Greek mythology, associated with figures like Hermes, Hecate, Orpheus, and Circe. Circe, renowned for her mastery of herbs and potions, aided Odysseus in summoning spirits. Myths featured magical potions and curses, such as the tragic story of Hercules’ death from the poisoned blood of the centaur Nessos.

What were the beliefs about magic in Greek society?

Magic was not restricted to the uneducated or private individuals; it was officially recognized by city-states. Inscriptions were commissioned to ward off disasters, and laws were enacted against harmful magic. For instance, Theoris was executed in the 4th century BCE for distributing incantations and drugs. Even philosophers like Plato acknowledged the potential misuse of magic.

What were Greek amulets, and how were they used?

Amulets were objects worn for protection, good fortune, or healing. They were categorized as talismans for good luck and phylacteries for protection. Made from materials like wood, stone, and bone, amulets were often designed as phallic symbols, knots, or scarabs. Their power was believed to be activated by invoking deities like Hecate or reciting specific chants.

What were curse tablets, and how were they used?

Curse tablets, known as agos, ara, or euche, were inscribed metal sheets—typically lead—buried in symbolic locations such as tombs or wells. Some were wax or clay figurines resembling the cursed individual, bound or nailed to amplify their effect. These tablets were used to address disputes, revenge, or competitions.

What were magic spells in ancient Greece?

Greek magic spells were detailed instructions often derived from Egyptian traditions. Surviving papyri from the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE provide guidance for treating ailments, enhancing love lives, exorcisms, and crafting amulets. These texts also include recipes for poisons and preparations involving rare herbs and exotic ingredients.