Etruscan Religion and Pantheon

The Etruscan civilization, which flourished in central Italy from approximately the 9th to the 1st century BCE, possessed a rich religious system heavily influenced by both indigenous traditions and external cultures, particularly Greek and Italic beliefs.

The Etruscan pantheon was a complex array of deities governing various aspects of human existence and the cosmos, often mirroring gods from Greek and Roman mythology but maintaining distinct attributes, iconography, and roles.

Etruscan religion was deeply ritualistic, based on the interpretation of divine will through signs, omens, and sacred texts such as the Etrusca Disciplina. The priesthood, especially the haruspices (who read animal entrails), played a crucial role in understanding divine messages. The gods were perceived as powerful beings who influenced human fate and needed constant appeasement through prayers, sacrifices, and rituals.

Origins and Structure of the Pantheon

The Etruscan pantheon evolved from indigenous Italic traditions, but as the civilization expanded and interacted with neighboring cultures, many Greek deities were assimilated, often under different names and functions. The hierarchy of gods was well-defined, with supreme deities governing the universe, intermediary gods managing specific domains, and minor deities overseeing daily affairs.

The Etruscan pantheon was a sophisticated and deeply ritualistic system that intertwined mythology, divination, and civic life.

A unique feature of Etruscan religion was its triadic structure, where groups of three major gods were worshiped together in temples. This trinity model would later influence the Romans, as seen in the Capitoline Triad (Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva).

Supreme Deities

At the highest level of the Etruscan pantheon stood Tinia, Uni, and Menrva, who formed a divine triad akin to the later Roman Capitoline Triad.

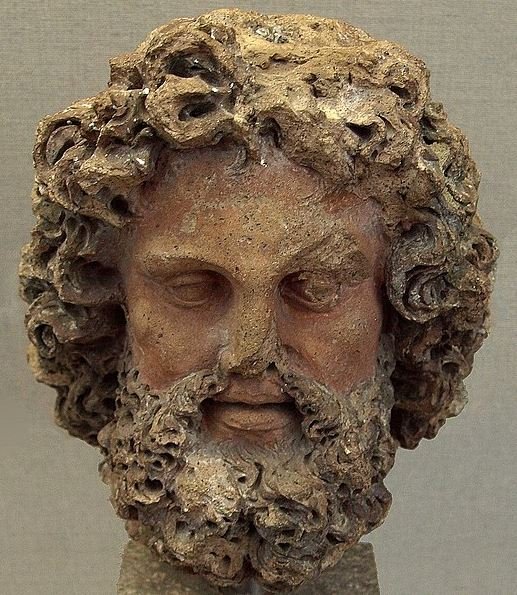

Tinia (or Tin)

Bust of Tinia.

- The supreme god of the Etruscans, comparable to Zeus (Greek) or Jupiter (Roman).

- Depicted as a bearded, powerful deity wielding thunderbolts.

- Associated with the sky, storms, and divine authority.

- Unlike Zeus or Jupiter, Tinia required divine approval from an assembly of gods before making crucial decisions.

Uni

Bust of Uni at the at the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia.

- The chief goddess and consort of Tinia, equivalent to Hera (Greek) and Juno (Roman).

- Patroness of marriage, childbirth, and protection of the Etruscan people.

- Often depicted with a diadem and holding a scepter.

- Worship of Uni was strong in cities like Veii, where she was identified with the local deity.

Menrva

- A goddess of wisdom, war, art, and healing, similar to Athena (Greek) and Minerva (Roman).

- Frequently depicted with a helmet, spear, and shield.

- Unlike the Greek Athena, she had more pronounced roles in healing and crafts.

- Associated with prophecy and divination, which played a crucial role in Etruscan religious practice.

Other Major Deities

In addition to the primary triad, several other gods held important positions in Etruscan belief:

Turan

Bust possibly depicting Turan.

- Goddess of love, beauty, and fertility, equivalent to Aphrodite (Greek) and Venus (Roman).

- Depicted as a youthful and graceful deity, often accompanied by swans or doves.

- Worshiped in Gravisca, an important Etruscan sanctuary dedicated to her.

Turan was the goddess of love and beauty, similar to Aphrodite, and was often depicted with her lover Atunis (Atune), the Etruscan equivalent of Adonis.

Fufluns

- God of wine, revelry, and vegetation, similar to Dionysus (Greek) and Bacchus (Roman).

- Had associations with the afterlife and renewal, reflecting Etruscan beliefs in the cycle of death and rebirth.

- Often depicted in processions, adorned with ivy and grapevines.

Veltha (or Voltumna)

- A chthonic deity linked to the underworld, fate, and cycles of life.

- Identified with the Roman Vertumnus, a god of seasonal change.

- Venerated as the chief deity of the Etruscan League, with a major sanctuary at Volsinii.

Laran

A statue of Laran.

- A war god, equivalent to Ares (Greek) and Mars (Roman).

- Portrayed as a youthful, athletic warrior, sometimes nude.

- Worshiped by soldiers and those seeking divine protection in battle.

Laran was the Etruscan god of war, usually shown in armor and sometimes depicted as the consort of Turan.

Maris

- A youthful deity associated with agriculture, fertility, and war.

- Sometimes depicted as a child, indicating his connection to rebirth and cycles of life.

Thesan

An ancient Etruscan mirror featuring an engraving of the goddess Thesan.

- Goddess of dawn and new beginnings, equivalent to Eos (Greek) and Aurora (Roman).

- Closely linked to fertility and childbirth.

Nethuns

- God of water, seas, and wells, equivalent to Poseidon (Greek) and Neptune (Roman).

- Portrayed with a trident and revered by sailors and those seeking safe voyages.

Nethuns, equivalent to Poseidon, was the Etruscan god of the sea and was often depicted with a trident.

Usil

A chariot fitting depicting Usil, dating to 500–475 BCE, housed in the Hermitage Museum.

- The solar deity, akin to Helios (Greek) and Sol (Roman).

- Depicted as a radiant figure driving a chariot across the sky.

Selvans

- A deity of boundaries and transitions, comparable to Hermes (Greek) and Mercury (Roman).

- Played a protective role over travelers and roads.

Chthonic and Underworld Deities in Etruscan Religion

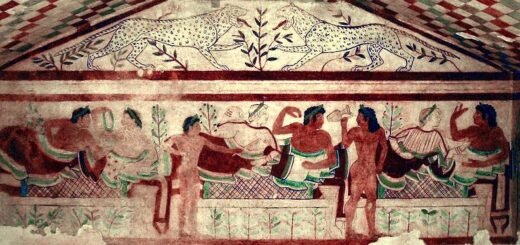

The Etruscans had a particularly strong emphasis on death, the afterlife, and underworld deities. Many of their tombs contained elaborate depictions of afterlife beliefs, showing gods and demons guiding souls.

Aita

- God of the underworld, equivalent to Hades (Greek) and Pluto (Roman).

- Often depicted wearing a wolf-skin headdress.

- His realm was not seen as a place of eternal torment but as a continuation of existence.

- Aita was not the focus of a formal cult, and it is believed that Calu, another Underworld deity, was worshiped instead.

Aita was the god of the Underworld, typically depicted wearing a wolf’s cap. His consort was Persipnei, and their presence is noted in tomb paintings.

Persipnei

- Consort of Aita, equivalent to Persephone (Greek) and Proserpina (Roman).

- Represented the seasonal cycle of life and death.

Vanth

Vanth was a female figure with wings who acted as a psychopomp, guiding souls into the afterlife. Image: Vanth depicted in a fresco within an Etruscan tomb in Tarquinia in Italy.

- A benevolent chthonic deity acting as a psychopomp (guide of souls).

- Usually depicted with wings, a torch, and sometimes a scroll listing a person’s fate.

- Unlike the Greek Erinyes (Furies), she was not malevolent but aided souls in transition.

Charun

- A fearsome underworld deity with blue skin, tusks, and a hammer.

- Served as an enforcer of death, ensuring souls reached their designated afterlife.

- Unlike Vanth, he had a more fearsome role, often depicted as a punisher.

Who are the major Chthonic Deities in Greek Religion and Mythology?

Divination and Worship

Religious rituals in Etruscan society were deeply tied to divination, a practice used to interpret the gods’ will. Priests, known as haruspices, read omens from animal entrails, lightning patterns, and bird flight. Sacred books, collectively known as the Etrusca Disciplina, guided these interpretations.

Temples dedicated to gods followed a standardized architectural style, usually rectangular with a deep front porch and high podium. Offerings included food, animal sacrifices, and ritual objects.

One of the most important religious sites was Fanum Voltumnae, the central sanctuary of the Etruscan League, dedicated to the god Voltumna. This was a place of political and religious gatherings, showcasing the importance of divine approval in Etruscan governance.

Legacy and Influence

Despite the eventual Roman conquest of Etruria, many Etruscan deities were absorbed into Roman religion. The triadic structure of gods, the practice of haruspicy, and the adaptation of deities like Menrva, Tinia, and Uni into Minerva, Jupiter, and Juno highlight Etruscan influence.

Additionally, the Etruscans’ underworld iconography and emphasis on fate left lasting impressions on Roman and even later Christian eschatology.

Frequently asked questions about the Etruscan Pantheon

What type of religion did the Etruscans practice?

The Etruscans practiced a deeply polytheistic religion, worshipping a wide range of deities, spirits, and divine beings.

Were all Etruscan deities native to their culture?

Some Etruscan deities were indigenous, while others were borrowed from neighboring cultures, particularly the Greeks, and adapted into an Etruscan framework.

How were Etruscan gods honored?

Etruscan gods were honored in temples and sanctuaries, and their presence was frequently depicted in art, including pottery, tomb paintings, sculptures, and engravings on objects such as bronze mirrors.

Why is our knowledge of Etruscan deities limited?

No complete Etruscan texts have survived, and only short inscriptions and votive offerings remain, making information about their gods scarce and often limited to names.

Who was Charu (Charun), and what role did he play?

Charu was a demonic figure associated with death, often depicted as a terrifying being with pointed ears, green skin, and a hammer, guarding the gates of the Underworld.

A fresco depicting Charun.

Who was the highest deity in the Etruscan pantheon?

Tinia (Tin) was the supreme deity, equivalent to Zeus or Jupiter, wielding thunderbolts and maintaining peace among the gods.

Tinia’s consort was Uni, a powerful goddess similar to Hera, who also had connections to the Phoenician deity Astarte.

What was Menerva (Menrva) known for?

Menerva, the Etruscan counterpart of Athena/Minerva, was associated with wisdom, warfare, and education, with significant temples dedicated to her.

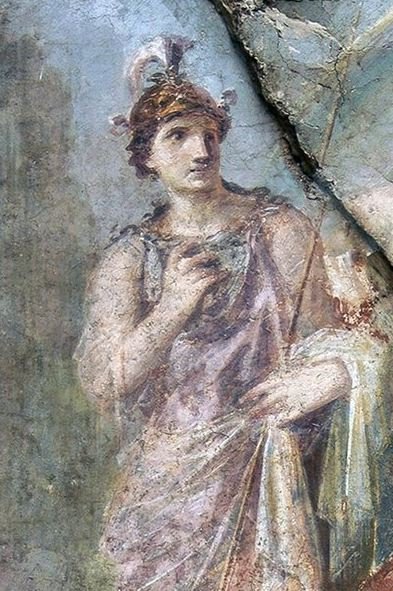

A fresco depicting Minerva.

How was fate represented in Etruscan religion?

Athrpa, a winged goddess, symbolized destiny and was shown driving a nail into a wall to signify the finality of fate.

What role did Nortia play in Etruscan religious rituals?

Nortia, linked to Menerva, had an annual ritual at her temple where a nail was hammered into the wall to mark the passing year.

Which deities represented celestial bodies?

Tivr (Tiur) was the goddess of the moon, while Usil was the sun god, often depicted with a radiant halo in Etruscan art.

Who was Tages, and why was he significant?

Tages was a miraculous child who appeared in a plowed field near Tarquinia and revealed sacred knowledge, forming the foundation of the Etruscan priestly tradition.

Who was Veltha (Voltumna), and what was their association?

Veltha, possibly the national god of Etruria, was associated with vegetation and seasonal change.

Which Etruscan deity was linked to forests and boundaries?

Selvans (Silvanus) was a god of forests, pastures, and boundaries.

What was Sethlans the god of?

Sethlans was the Etruscan equivalent of Hephaistos/Vulcan, the god of fire and metalworking.

Who was Fufluns, and what was his role?

Fufluns, associated with Dionysos, was the god of wine, revelry, and rebirth, often depicted with satyrs and maenads.

How was Hercle viewed in Etruscan mythology?

Unlike his Greek counterpart, the Etruscan Hercle (Hercules) was always considered a god rather than a hero.

What was the function of Culsans and Culsu?

Culsans was a double-faced god of gates, similar to Janus, while Culsu was a female demon who guarded the entrance to the Underworld.

Who were the Novensiles, and what were they associated with?

The Novensiles were a group of nine gods associated with lightning and omens, influencing future events.

Who were the Dii Consentes?

The Dii Consentes were a council of twelve deities who advised Tinia and were known for being cold and impartial.

Who were the Lares and Lasa?

Lares were protectors of travelers and crossroads, while Lasa were attendants of Turan, sometimes associated with fate.

Who were Tinas Clenar, and how were they depicted?

Tinas Clenar, equivalent to Castor and Pollux, were the twin sons of Tinia, often shown wearing laurel wreaths.