Hanging Gardens of Babylon

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon stand as one of the most enigmatic and celebrated landmarks of the ancient world. Renowned as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, their existence has been a subject of fascination and debate for centuries. While classical accounts provide vivid descriptions, archaeological evidence remains elusive, contributing to the enduring mystery surrounding these legendary gardens.

In the article below, World History Edu delves into the historical context, architectural marvels, cultural significance, and the debates that shape our understanding of the Hanging Gardens.

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, were a marvel of engineering featuring tiered gardens with diverse flora, resembling a green mountain built of mud bricks. Image: Depiction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Historical Context

Said to be located in ancient Babylon, near present-day Hillah, Iraq, the gardens were reportedly constructed by King Nebuchadnezzar II for Queen Amytis to replicate her homeland’s lush landscapes. Image: A fragment of the Tower of Babel stele shows Nebuchadnezzar II on the right and Babylon’s Etemenanki ziggurat on the left.

Ancient Babylon: A Flourishing Metropolis

Babylon, situated near present-day Hillah in Iraq’s Babil province, was one of the most prominent cities of the ancient Near East.

Under the rule of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, particularly during King Nebuchadnezzar II’s reign (605–562 BC), Babylon experienced significant architectural and cultural advancements. The city was renowned for its grandeur, including impressive structures like the Ishtar Gate and the expansive ziggurat known as Etemenanki, which some associate with the biblical Tower of Babel.

Construction and Attribution

The Hanging Gardens are traditionally attributed to Nebuchadnezzar II, who purportedly built them to soothe his Median wife, Queen Amytis. According to Berossus, a Babylonian priest cited by Josephus, Amytis yearned for the green hills and valleys of her homeland, prompting Nebuchadnezzar to create a verdant paradise within the arid landscape of Babylon. This act not only showcased the king’s devotion but also demonstrated Babylon’s architectural and horticultural prowess.

However, alternative theories challenge this attribution. Stephanie Dalley, an Oxford scholar, posits that the gardens were actually constructed by Assyrian King Sennacherib in Nineveh, not Babylon. The British Assyriologist’s argument is based on Assyrian inscriptions and archaeological findings that detail sophisticated water systems and lush gardens in Nineveh, which align closely with classical descriptions of the Hanging Gardens.

Nebuchadnezzar and his wife watching the construction of the hanging gardens; René-Antoine Houasse

Architectural and Engineering Marvels

Georg Pencz’s woodcut from his 16th-century series “Tyrants of the Old Testament” portrays Nebuchadnezzar II alongside Babylon’s great ziggurat.

Design and Structure

Classical accounts by writers such as Diodorus Siculus and Quintus Curtius Rufus provide detailed descriptions of the gardens’ architecture. Diodorus describes a square-shaped complex with each side measuring approximately 120 meters. The gardens were tiered, with the highest gallery reaching about 22 meters, supported by massive brick walls 6.7 meters thick. This tiered design created an illusion of a cascading mountain, adorned with a diverse array of trees, shrubs, and vines.

Quintus Curtius Rufus adds that the gardens were situated atop a citadel with a circumference of roughly 3.7 kilometers, emphasizing their elevated position and expansive layout. This strategic placement not only provided stability to the extensive structure but also maximized the aesthetic impact of the gardens, making them visible from various vantage points within the city.

Irrigation Systems

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Hanging Gardens was their sophisticated irrigation system. Strabo and Philo of Byzantium highlight the use of Archimedes’ screws, an ingenious mechanism for lifting water from the Euphrates River to the elevated gardens. This technology was crucial in sustaining the lush vegetation in an otherwise arid environment. The water had to be efficiently distributed across multiple levels, necessitating advanced engineering techniques.

Effective irrigation was crucial for maintaining the health and vitality of the gardens. The advanced water management systems ensured a consistent supply of water, preventing drought stress and enabling the cultivation of a wide range of plant species.

The Assyrian king employed an extensive network of canals and aqueducts, spanning approximately 80 kilometers, to transport water from distant sources. The aqueduct at Jerwan, constructed with over two million stone blocks, exemplifies the monumental effort invested in ensuring a reliable water supply. This system included automatic sluice gates and water-raising screws, enabling the maintenance of the gardens’ verdant terraces.

Botanical Diversity and Landscaping

The botanical richness of the Hanging Gardens was another testament to their grandeur. Indigenous species such as date palms, figs, almonds, olives, grapes, and tamarisk thrived alongside imported varieties like cedars, cypresses, ebony, pomegranates, junipers, oaks, and walnuts. This diverse flora not only provided aesthetic beauty but also demonstrated the exchange of botanical knowledge and plant species across regions.

The plants were meticulously arranged in terraces, creating layers of greenery that cascaded down the tiered structure. Burbling waterfalls and flowing water enhanced the sensory experience, making the gardens a serene oasis amidst the bustling city. The integration of water features with lush vegetation exemplified the harmonious blend of nature and human ingenuity.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

The Hanging Gardens were more than just a botanical marvel; they were a powerful symbol of the ruler’s wealth, sophistication, and ability to command resources. Constructing such an elaborate garden in a city like Babylon underscored Nebuchadnezzar II’s reign as a period of prosperity and cultural flourishing. It reflected the empire’s dominance and its capability to undertake monumental projects that required extensive planning and resources.

The gardens also served as a hub for cultural exchange. The variety of plant species indicates a blend of local and foreign influences, showcasing the interconnectedness of the ancient world. Gardens like these facilitated the exchange of botanical knowledge, agricultural techniques, and aesthetic principles across different civilizations, contributing to a shared heritage of horticultural excellence.

The Hanging Gardens, with their lush greenery and intricate water features, epitomized this divine harmony, serving as a living testament to the interconnectedness of nature and human endeavor.

The Hanging Gardens have inspired countless generations in art, literature, and architecture. Their depiction in various forms of media underscores their enduring allure and the human fascination with creating paradisiacal spaces. The gardens symbolize an idealized harmony between nature and human craftsmanship, inspiring modern architectural and landscape designs that seek to emulate their beauty and complexity.

In the context of Mesopotamian religion and mythology, gardens held significant symbolic meaning. They were often associated with divine favor, fertility, and the benevolence of the gods. The Hanging Gardens, with their lush greenery and elaborate water features, could be interpreted as a manifestation of divine grace bestowed upon the city by its ruler, reinforcing the connection between the monarchy and the divine.

Historical Debates and Theories

Despite detailed descriptions from classical writers, no definitive Babylonian texts or archaeological findings have confirmed the existence of the Hanging Gardens. Nebuchadnezzar II’s inscriptions, which extensively document his construction projects, make no mention of such gardens. This absence has fueled skepticism about their historical reality, leading some scholars to question whether the gardens were purely mythical or exaggerated in later accounts.

One prevailing theory is that the Hanging Gardens were a poetic or symbolic creation rather than a physical structure. Ancient Greek and Roman writers may have envisioned the gardens as an idealized representation of an eastern paradise, embodying the virtues of beauty, abundance, and technological prowess. In this view, the gardens serve more as a literary symbol of human ingenuity and the allure of the exotic East than as a factual monument.

Another theory posits that the gardens did exist but were destroyed, leaving no archaeological trace. Factors such as natural disasters, wars, or shifting river courses could have led to the garden’s demise. The Euphrates River’s changing course over millennia complicates archaeological efforts, as much of ancient Babylon lies beneath the modern riverbed, making excavation challenging. If the gardens were destroyed or submerged, evidence might still be inaccessible or yet to be discovered.

Stephanie Dalley’s compelling theory suggests that the Hanging Gardens were not located in Babylon but in Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian Empire under King Sennacherib. Dalley argues that classical accounts conflated the impressive gardens of Nineveh with Babylon, possibly due to the broader use of the name “Babylon” for several Mesopotamian cities. Her research highlights Assyrian inscriptions and archaeological evidence of advanced irrigation systems in Nineveh that align with descriptions of the Hanging Gardens.

Dalley points out that Sennacherib’s gardens featured extensive canal networks, sophisticated water-raising screws, and terraced landscaping, mirroring the classical accounts of Babylon’s gardens. Additionally, the Assyrian king’s inscriptions and sculptural reliefs depicting lush gardens bolster the argument for Nineveh as the true location of the Hanging Gardens. This theory reconciles the detailed descriptions with existing archaeological evidence, offering a plausible resolution to the historical debate.

Sennacherib’s Gardens at Nineveh

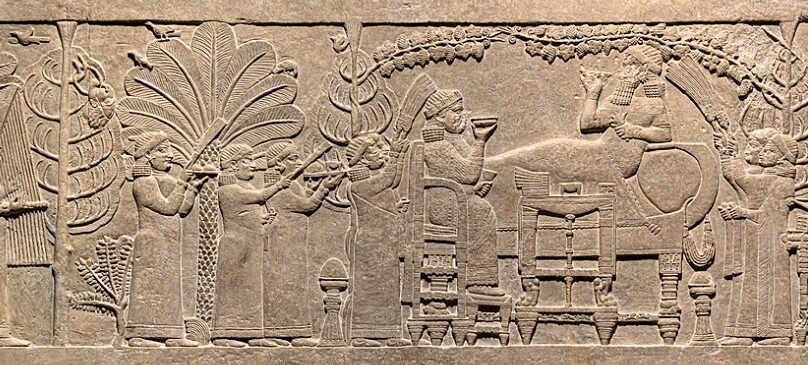

Gardens in ancient Mesopotamia were often seen as reflections of divine creation, embodying the harmony and balance of the natural world. The “Garden Party” relief from Nineveh’s North Palace (c. 645 BC) shows Ashurbanipal and his wife under grapevines, surrounded by date palms, pine trees, birds, and a defeated king’s head.

Assyrian King Sennacherib’s gardens in Nineveh were a marvel of engineering, featuring an intricate system of canals and aqueducts designed to transport water from the mountains to the city. The Jerwan Aqueduct, constructed with over two million dressed stone blocks, exemplifies the monumental effort invested in these projects. The aqueduct’s design included stone arches and waterproof cement, ensuring the efficient flow of water across steep valleys.

Sennacherib employed screw mechanisms to elevate water to higher levels within the gardens. These devices, possibly similar to Archimedes’ screws, enabled the distribution of water across the terraced gardens, maintaining the lush vegetation and supporting diverse plant life. The use of such technology underscores the Assyrians’ advanced understanding of hydraulics and their ability to implement complex engineering solutions.

Sennacherib’s sculptural reliefs from his North Palace at Nineveh depict lush gardens with abundant plant life, resembling the classical descriptions of the Hanging Gardens. These artistic representations provide visual evidence of the gardens’ grandeur, illustrating cascading greenery, water features, and terraced layouts that align with historical accounts. The presence of such reliefs supports the identification of Nineveh’s gardens with the legendary Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

The terraced design of the gardens facilitated the cultivation of diverse plant species by providing varied microenvironments. Each terrace could support different types of vegetation, creating a layered and harmonious landscape.

For Sennacherib, the gardens were a testament to Assyrian power and cultural sophistication. By constructing a verdant oasis in the heart of Nineveh, he demonstrated his ability to transform the natural landscape and provide for his people’s aesthetic and practical needs. The gardens served as a symbol of prosperity, technological advancement, and the king’s benevolence, reinforcing his legitimacy and authority.

Excavations in Nineveh have unearthed remnants of the extensive water systems that supported the gardens. The Jerwan Aqueduct and other canal structures reveal the scale and complexity of the irrigation efforts. Additionally, remnants of the palace and its gardens, although not entirely intact, provide tangible links to the descriptions found in classical texts. These findings lend credence to the theory that Nineveh, rather than Babylon, was the true site of the Hanging Gardens.

Influence on Later Gardens and Modern Perceptions

Assyrian wall relief showing gardens in Nineveh

The concept of tiered gardens with elaborate irrigation systems influenced garden designs in subsequent civilizations. Persian gardens, for example, drew inspiration from the Hanging Gardens’ terraced layouts and emphasis on water features. The idea of creating a paradise through meticulous landscaping and water management can be seen in the gardens of the Islamic world, Renaissance Europe, and beyond.

Throughout history, the Hanging Gardens have been a symbol of beauty, luxury, and the pinnacle of human achievement. They feature prominently in literature, art, and folklore, often representing an idyllic or utopian vision. This symbolic presence underscores the gardens’ enduring impact on cultural imagination, inspiring artists and writers to envision their own paradises.

The arrangement of plants in terraces also optimized space usage, allowing for the growth of large trees and dense foliage without overcrowding.

Modern attempts to recreate or visualize the Hanging Gardens have emerged in museums, digital media, and scholarly reconstructions. These efforts aim to bridge the gap between classical descriptions and archaeological findings, offering contemporary audiences a glimpse into what the gardens might have looked like. While speculative, these reconstructions highlight the gardens’ architectural and horticultural sophistication, emphasizing their role as a wonder of the ancient world.

Conclusion

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon remain one of history’s most captivating and debated wonders. Whether a historical reality, a mythological symbol, or a conflation of different ancient gardens, their legacy as a pinnacle of ancient engineering and horticultural artistry is unquestionable. The gardens embody the human aspiration to create beauty and harmony through meticulous design and technological innovation.

Frequently Asked Questions

The botanical diversity of the Hanging Gardens was a key feature, showcasing both indigenous and exotic plant species. Indigenous plants like date palms, figs, almonds, olives, grapes, and tamarisk thrived alongside imported varieties such as cedars, cypresses, ebony, pomegranates, junipers, oaks, and walnuts.

Who are the five principal ancient writers describing the Hanging Gardens of Babylon?

The five principal writers are Josephus, Diodorus Siculus, Quintus Curtius Rufus, Strabo, and Philo of Byzantium. Each provided unique accounts detailing the gardens’ design, purpose, and engineering.

According to Josephus, who built the Hanging Gardens and for what purpose?

Josephus quotes Berossus, who attributes the construction of the Hanging Gardens to King Nebuchadnezzar II. They were built to please his Median wife, Amytis, who missed her homeland’s mountainous landscapes.

How does Diodorus Siculus describe the design and structure of the Hanging Gardens?

Diodorus describes the gardens as square-shaped with each side measuring four plethra (~120 meters). They were tiered, with the highest gallery 50 cubits (~22 meters) tall, supported by 22-foot-thick brick walls, and irrigated using water from the Euphrates River.

What unique feature does Quintus Curtius Rufus highlight about the location of the Hanging Gardens?

Quintus Curtius Rufus states that the gardens were situated atop a citadel with a circumference of 20 stadia (~3.7 kilometers). He also attributes their construction to a “Syrian king” for a homesick queen.

What irrigation technology does Strabo attribute to the Hanging Gardens?

Strabo describes an irrigation system using an Archimedes’ screw to lift water from the Euphrates River to the elevated gardens, highlighting the engineering ingenuity required to sustain them.

What contributions does Philo of Byzantium make to the description of the Hanging Gardens?

In his Handbook to the Seven Wonders of the World, Philo praises the technical brilliance of the gardens’ deep soil terraces and advanced irrigation system, echoing Strabo’s mention of screw mechanisms for raising water.

What are the three main theories regarding the historical existence of the Hanging Gardens?

- Mythical Creation: The gardens were poetic symbols of an idealized paradise.

- Destruction: They existed but were destroyed around the 1st century AD, leaving no evidence.

- Misattribution to Babylon: The gardens were actually in Nineveh, built by Assyrian King Sennacherib, with later accounts mistakenly attributing them to Babylon.

How does Stephanie Dalley support the theory that the Hanging Gardens were located in Nineveh?

Dalley points to Assyrian inscriptions and archaeological findings of advanced aqueducts near Nineveh, which match classical descriptions. She notes that Sennacherib documented his sophisticated water systems extensively, unlike Nebuchadnezzar, and suggests Greek writers may have conflated Nineveh with Babylon.

What evidence links Sennacherib’s gardens at Nineveh to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon?

Evidence includes the aqueduct at Jerwan built with over two million stone blocks, Assyrian King Sennacherib’s detailed inscriptions on water engineering, sculptural reliefs depicting lush gardens, and the use of screw mechanisms for irrigation, all aligning with classical descriptions of the Hanging Gardens.

What types of plants were likely featured in the Hanging Gardens, and how were they arranged?

The gardens likely included indigenous species such as date palms, figs, almonds, olives, grapes, and tamarisk, alongside imported varieties like cedars, cypresses, ebony, pomegranates, junipers, oaks, and walnuts. These plants were arranged in terraces, creating a lush, verdant spectacle with cascading greenery and flowing water.