10 Most Remarkable Archaeological Finds in History

Across centuries of exploration, remarkable discoveries have emerged to illuminate human innovation, culture, and beliefs. World History Edu presents ten finds that have forever altered how we interpret humanity’s collective story.

Tutankhamun’s Tomb

The Terracotta Army

Discovered in 1974 near Xi’an, China, the Terracotta Army is a monumental archaeological find created to guard the mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of unified China. Thousands of life-sized clay soldiers, each uniquely crafted with distinct facial features, hairstyles, and uniforms, stand alongside chariots, cavalry, musicians, and acrobats, reflecting an imperial entourage designed for the afterlife. Built around 221 BCE, the mausoleum demonstrates the vast organizational capacity and labor resources of the Qin Dynasty, showcasing advanced artistry and administrative prowess.

Terracotta sculptures were interred alongside Emperor Qin Shi Huang of the Qin Dynasty. These clay-crafted warriors were intended to serve as guardians for the emperor on his journey to the afterlife.

The Terracotta Army revolutionized our understanding of early imperial China. Each figure’s individual design reveals sophisticated craftsmanship, early assembly-line techniques, and complex kiln-firing and painting methods. This discovery provides invaluable insights into the administrative systems and centralized authority underpinning Qin Shi Huang’s reign, shaped by legalist philosophy emphasizing control and efficiency.

Modern research continues to analyze the materials and construction techniques, uncovering details about pigment use and production processes. Ongoing excavations frequently unveil new artifacts, many retaining traces of their original colors, further deepening our knowledge of Qin-era artistry and the emperor’s grand vision for immortality.

Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu, a marvel of Inca architecture, sits 2,430 meters above sea level in the Andes of Peru. Although known locally, it gained international recognition in 1911 through historian Hiram Bingham. Constructed in the 15th century, possibly under Inca ruler Pachacuti, this site features meticulously carved stone buildings and advanced canal systems for water management. Its terraces enabled crop cultivation despite the steep terrain, showcasing the Inca’s engineering and agricultural expertise.

Archaeological debates persist over its purpose, with theories ranging from a royal estate to a ceremonial center. Its layout reflects Inca cosmology, with temples aligned to celestial events, emphasizing their astronomical knowledge. Excavations have uncovered tools, pottery, and farming evidence, revealing its connections to wider social and economic networks.

Machu Picchu’s seamless integration with the natural landscape illustrates the Inca ethos of harmony with the environment.

Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983, Machu Picchu remains a testament to pre-Columbian ingenuity and cultural resilience

The Curse of the Lost Inca Gold: Origin Story and Significance

Pompeii

In 79 CE, Pompeii was buried under volcanic ash and pumice following Mount Vesuvius’s eruption, preserving a Roman city frozen in time. Rediscovered in the late 16th century, systematic excavations began in the 18th century, revealing frescoes, mosaics, carbonized scrolls, and intact streetscapes. From bakeries to lavish villas, artifacts showcased daily Roman life, while plaster casts of voids in the ash captured human figures in their final moments.

Temple of Isis in Pompeii

Pompeii offers an unmatched glimpse into first-century urban life. Wealthy domus, modest workshops, and public spaces highlight social diversity. Graffiti and electoral notices reveal political and communal dynamics, while remnants of food and advanced sanitation systems detail dietary habits and hygiene practices. The city’s preserved artworks, from mythological frescoes to everyday motifs, provide a vivid understanding of Roman aesthetics. Pompeii’s unparalleled preservation reshaped our understanding of Roman society, offering a poignant, detailed, and humanized view of a thriving civilization abruptly halted by catastrophe.

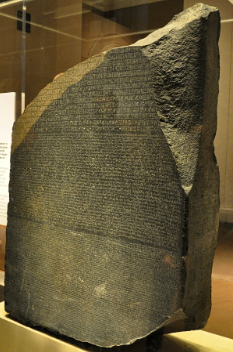

The Rosetta Stone

Discovered in 1799 near Rosetta, Egypt, the Rosetta Stone is a granodiorite slab inscribed with a decree honoring Ptolemy V in three scripts: hieroglyphic, Demotic, and Ancient Greek. At the time, hieroglyphs were an unsolved mystery, but the Greek text provided a critical comparative tool. In the early 19th century, Jean-François Champollion deciphered the hieroglyphs, proving they represented both sounds and ideas.

Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone revolutionized Egyptology by enabling the translation of hieroglyphic texts on temples, tombs, and papyri. This breakthrough unveiled the complexities of ancient Egyptian civilization, including its history, religion, and governance. Scholars could now decipher royal decrees, mythological stories, and administrative records spanning millennia, shedding light on pharaohs, deities like Ra and Osiris, and daily Nile Valley life. Housed in the British Museum since 1802, the stone symbolizes the power of linguistic discovery and the collaborative spirit that reshaped historical understanding worldwide.

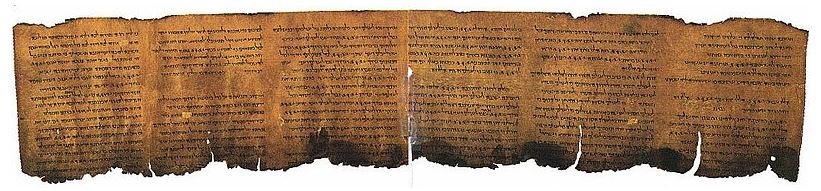

The Dead Sea Scrolls

Discovered between 1947 and 1956 in caves near the Dead Sea, the Dead Sea Scrolls comprise ancient manuscripts, including Hebrew Biblical texts, non-canonical Jewish writings, and sectarian documents. Found by Bedouin herders, these scrolls date from the third century BCE to the first century CE, preserved in sealed jars for centuries. They are attributed to a Jewish sect, possibly the Essenes, and provide unparalleled insights into Second Temple Judaism and early scriptural traditions.

The scrolls transformed our understanding of the Hebrew Bible’s evolution, revealing variations and continuities with the later Masoretic Text. Sectarian works like the Community Rule and War Scroll illuminate liturgical practices, eschatological beliefs, and social structures of Jewish groups during the late Hellenistic and Roman periods. Modern analysis, including radiocarbon dating and imaging technologies, continues to refine knowledge of scribal practices. The scrolls also contextualize early Christianity, bridging critical historical and cultural gaps.

The Great Psalms Scroll is one of the 981 manuscripts that make up the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Lascaux Cave Paintings

Discovered in 1940 by teenagers in southwestern France, Lascaux Cave houses stunning Paleolithic paintings of animals such as horses, deer, and aurochs, along with geometric symbols. Dating back around 17,000 years, these artworks were created using natural pigments like iron oxides and charcoal, applied with brushes or sprayed through hollow bones. The intricate shading, motion, and proportions demonstrate the artistic sophistication of Cro-Magnon humans, challenging stereotypes of early humans as mere hunters.

Dubbed the “Sistine Chapel of Prehistory,” Lascaux offers insights into early symbolic or ritualistic expression, though its meaning remains debated. Initially opened to visitors, the cave’s art deteriorated due to carbon dioxide and microbial growth, prompting its closure in 1963. Accurate replicas like Lascaux II and digital technologies preserve and share this heritage.

Lascaux Cave Paintings of a dun horse.

Göbekli Tepe

Lucy – the Hominin Fossil

In 1974, Donald Johanson and Tom Gray discovered a partial skeleton in Ethiopia’s Afar Depression, later named Lucy, belonging to Australopithecus afarensis. Dated to 3.2 million years ago, Lucy provided crucial evidence of bipedal locomotion, shown by her pelvis and knee structure, while her small skull highlighted that upright walking preceded brain expansion in human evolution. Her name was inspired by the Beatles’ song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” played at the team’s camp.

A plaster replica of Lucy on display at the National Museum of Ethiopia.

Lucy’s skeletal features—human-like bipedal adaptations alongside ape-like traits such as long arms and curved fingers—illustrated a transitional phase in evolution. Her discovery spurred further research in East Africa, revealing additional fossils of Australopithecus afarensis and related species.

Researchers linked her adaptations to environmental shifts, suggesting upright walking evolved for efficient movement in reduced forest cover. Lucy reshaped paleoanthropology, refining theories on growth, social behavior, and the balance between arboreal and terrestrial lifestyles in early hominins.